BLOG

Weaving a circular & regenerative wool economy

Weaving a circular & regenerative wool economy

Weaving a circular & regenerative wool economy in Blönduós

Towards a New Fiber Economy

Words by the Icelandic Textile Center & Metabolic

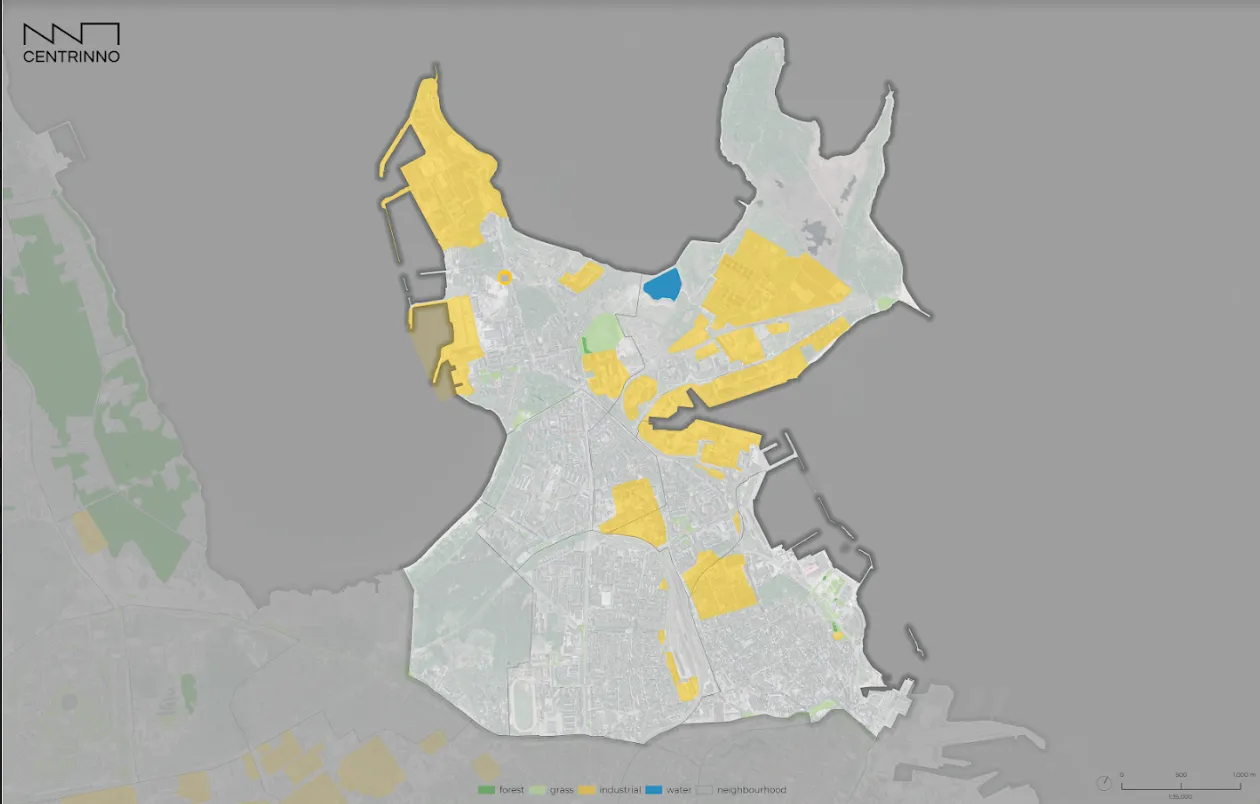

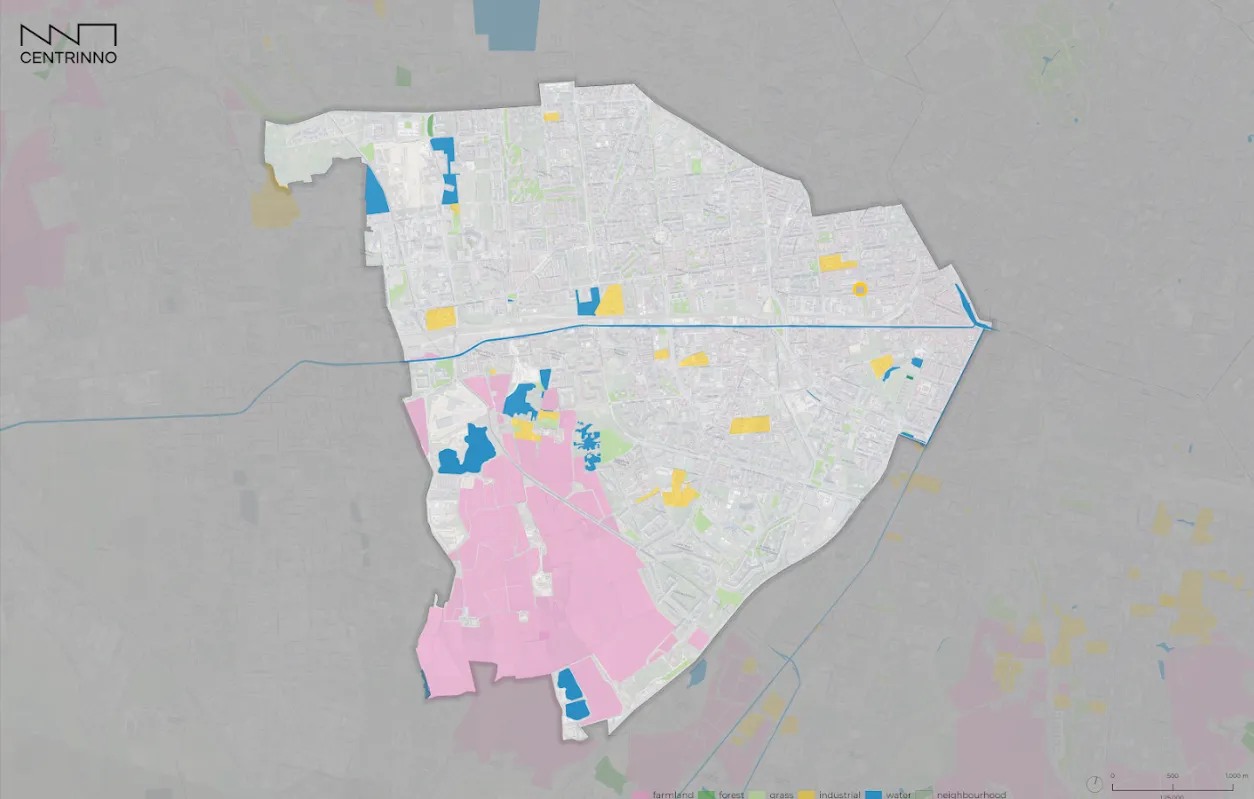

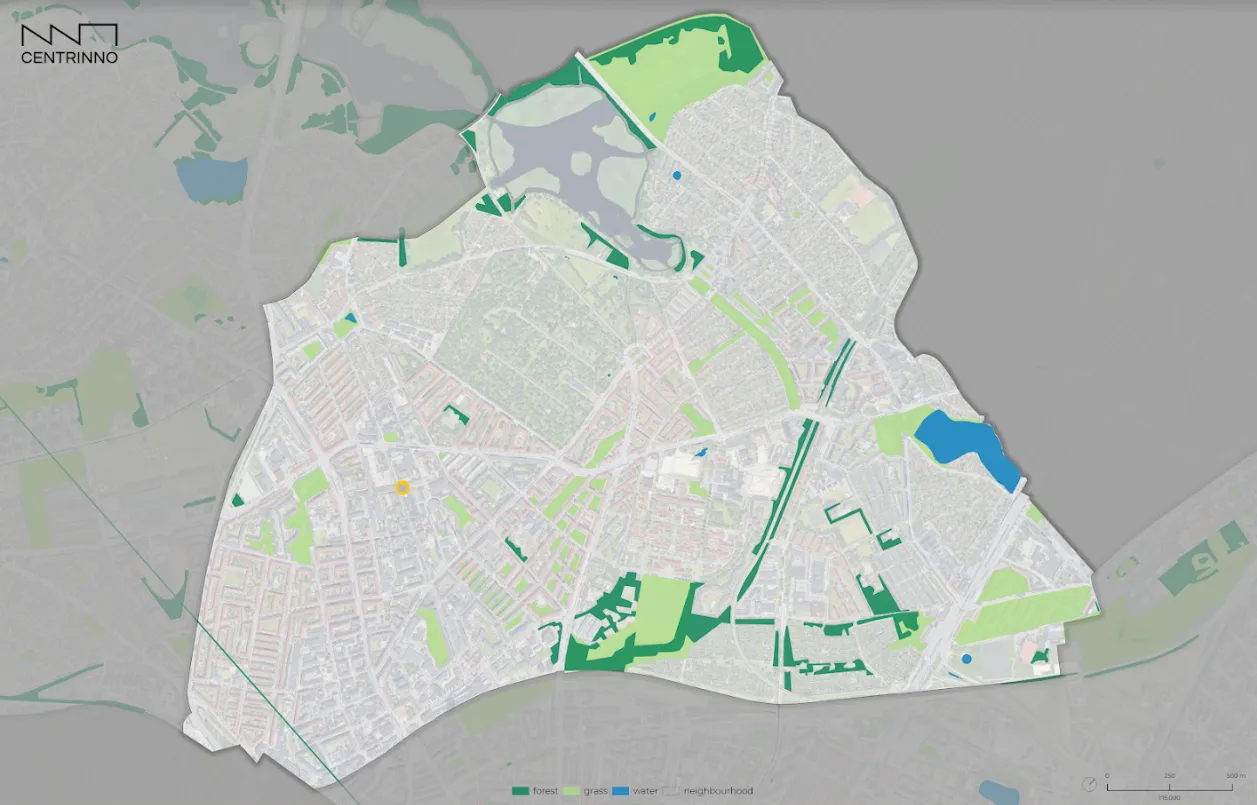

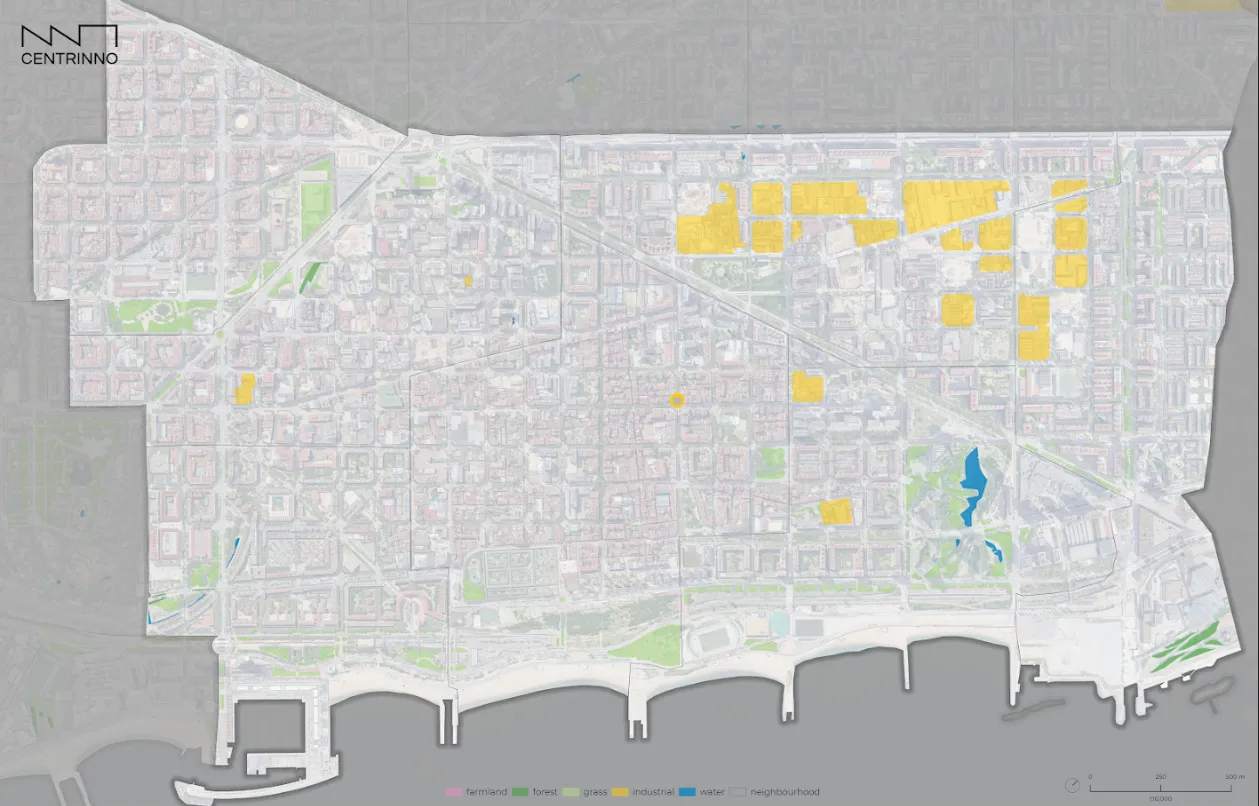

ABOUT THE PILOT AREA

Pilot area: Blönduós?

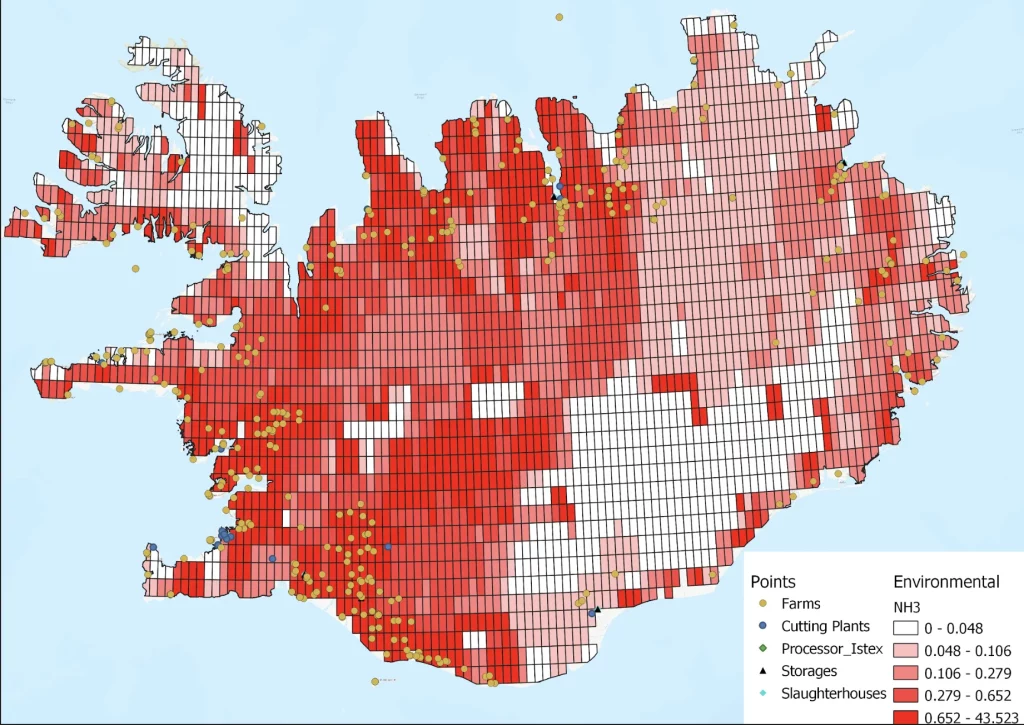

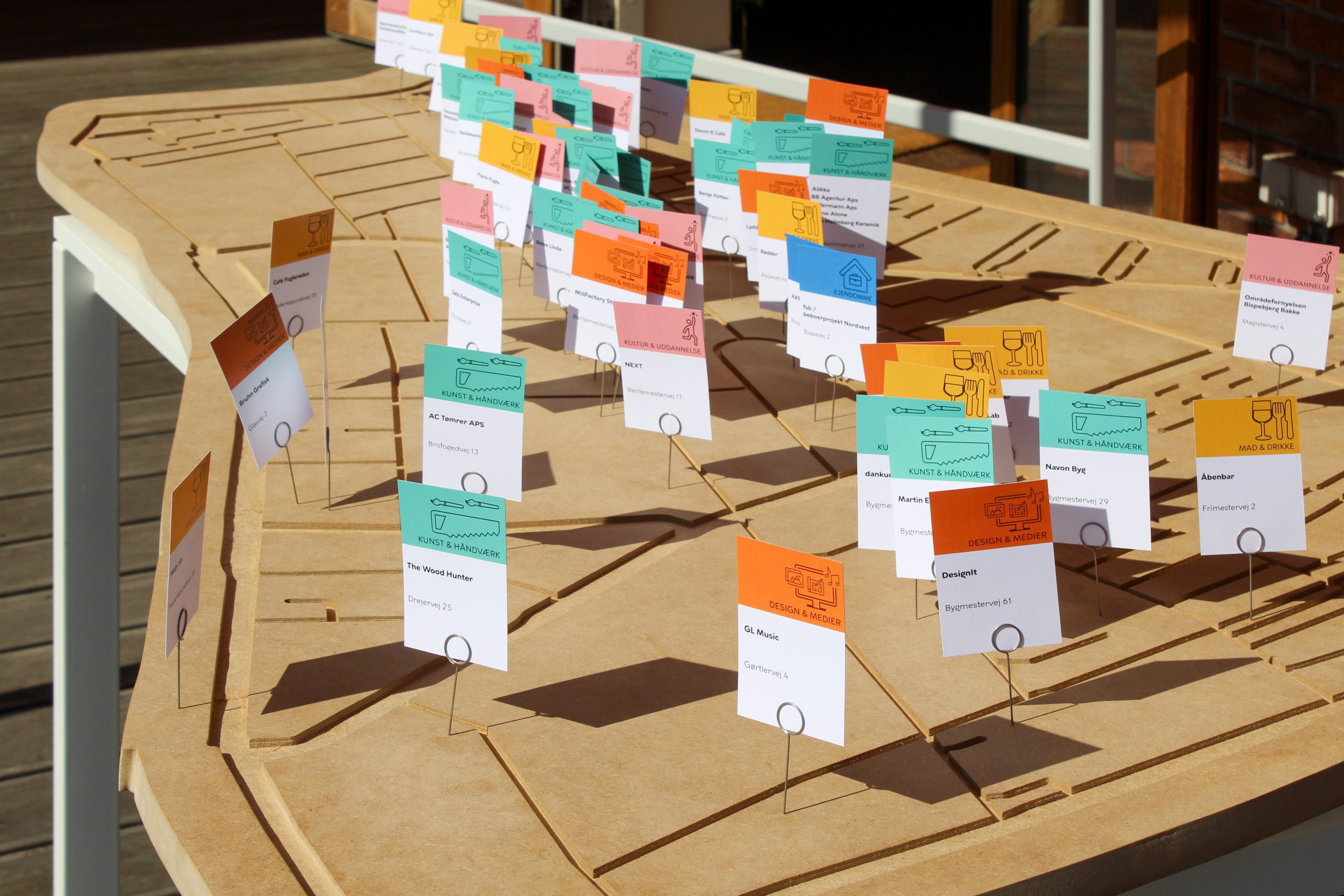

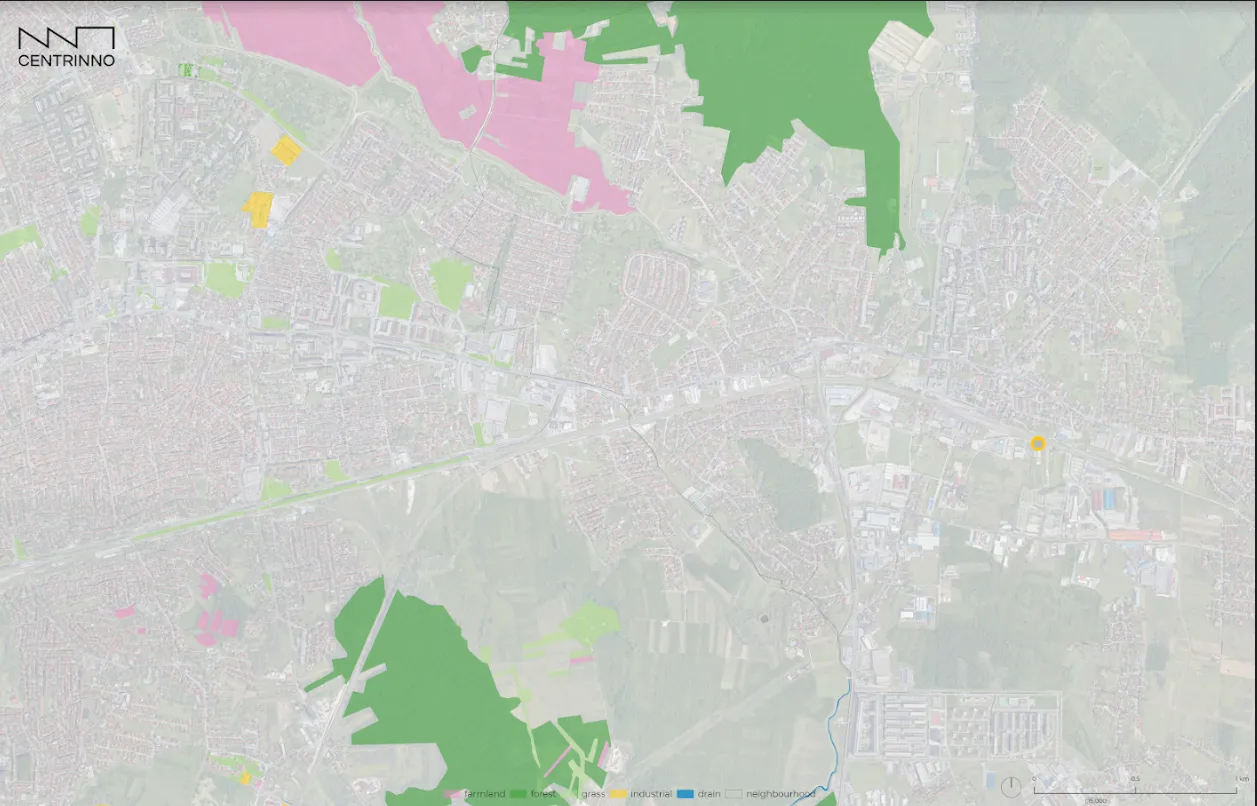

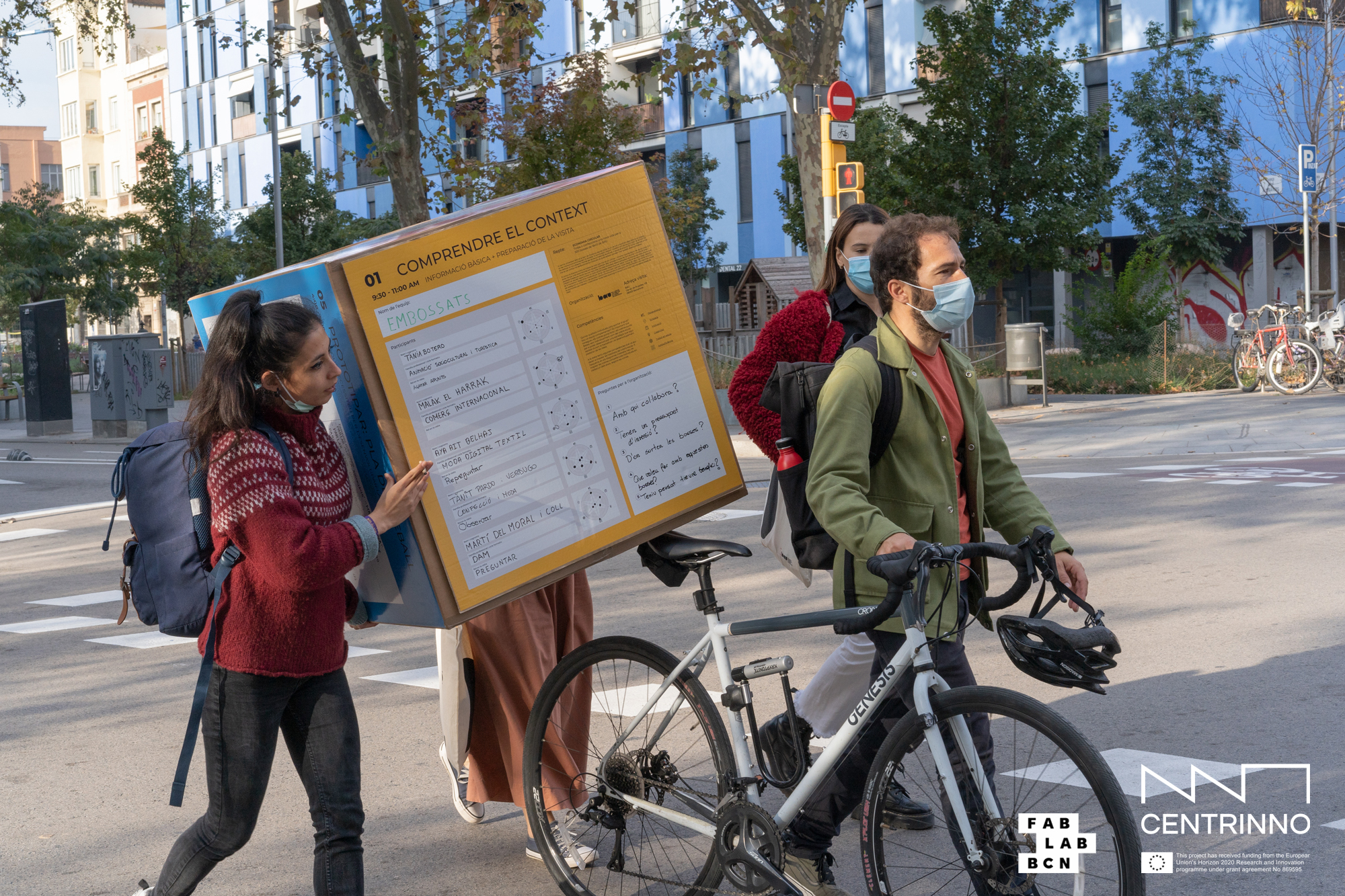

Blönduós, a small town in Northwest Iceland, is home to Iceland’s Textile Center – a place for fostering innovation and collaboration across Icelandic and international wool and textile sector. As part of CENTRINNO, the team has mapped wool and textile material flows and the most important stakeholders across the country and the wool value chain. The goal of our mapping across Iceland is to identify potentials for a circular wool economy and alternative fibre resources for a diversified, circular and resilient textile industry across Iceland’s sheep farmers, yarn producers, knitting factories, designers and other wool-related actors.

How can we build a regenerative wool and textile ecosystem in Iceland?

From spring to autumn, Iceland’s lowlands, mountains and coasts are home to over 400,000 sheep, roaming freely and grazing on wild plants, heather and seaweed until winter nears. Outnumbering Iceland’s human population, this number might seem a lot. But back in the 1980’s, the size of Iceland’s sheep flocks was twice of what it is today[1]. The Icelandic sheep, which are said to have been introduced to the island in the 9th or 10th century, offer a significant source of meat and wool for local inhabitants[2].

The factors that fueled the decline of Icelandic sheep were complex and numerous. Firstly, and most importantly, government quotas imposed around the 1980s concerning the production of sheep meat were important drivers[3]. Secondly, factors like changed social and consumption patterns and market challenges related to production costs and income, played a role in further sustaining the decline in the number of sheep roaming Iceland[4]. The Icelandic government has also played a substantial role in the upkeep of sheep farms, for example by providing export subsidies for sheep meat during the 1970s[1].

Interestingly however, for this now smaller number of Icelandic sheep, not their meat but rather their wool has become more relevant than ever, especially in the more recent pandemic years[5,6]. The Icelandic sheep is of the Northern European short-tailed sheep breed. Their wool is special in that it contains two different types of hair: The outer layer is composed of coarse, long hair known in Icelandic as tog, a tough and water-resistant layer. Underneath, there is a layer of finer and softer, short hair, called þel. The two different layers can be separated and used for different types of yarn.

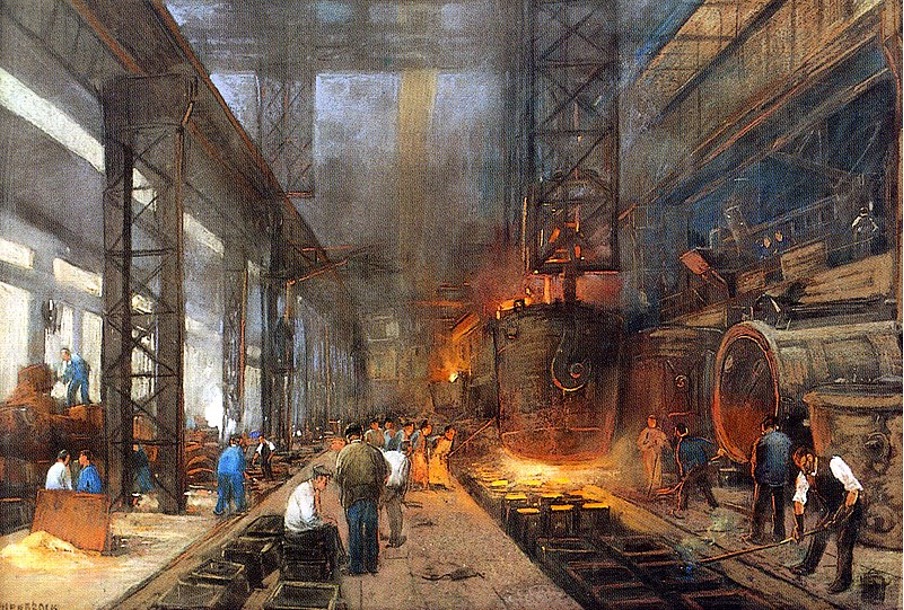

Image 1. Source: Katharina Schneider

A short glimpse into the Icelandic wool market

Icelandic wool and wool garments made in Iceland have reached global popularity – especially with the million tourists and more visiting Iceland each year. Some garments are indeed hand-knit e.g. from members of the Handknitting Association of Iceland and locally produced from small producers such as Varma and Kidka. To meet the rising demand for wool products, companies such as Icewear are sending wool and woolen yarn to places all around the world where labor costs are significantly cheaper[7]. Knitting and further processing happens in China, Latvia and Romania before being re-imported into the Icelandic market, where they often end up in the hands of visiting tourists or are sold online. The consequence of wool’s complex journey before it reaches our closets is a whole lot of freight and air miles with heavy carbon footprints.

Consumers are not always aware of the long journeys hidden in their garments. In recent years, a clothing manufacturer was accused of labeling clothing as if they were made in Iceland, whilst in actuality the clothes were manufactured and often also sourced abroad[8]. The company was later fined by the Icelandic consumer agency, triggering a legal process that eventually led to the “Icelandic Sweater Protection Act” which prohibits the production of the Icelandic sweater outside of the country. It is not only wool being manufactured abroad that contributes to the large number of textile imports. Indeed, Iceland’s wool industry, despite its high-quality products and growing global demand, struggles to compete with lower-quality fast fashion that floods the local market. In 2019 alone, the local wool production was outnumbered by imported textiles by a factor of 11.

?

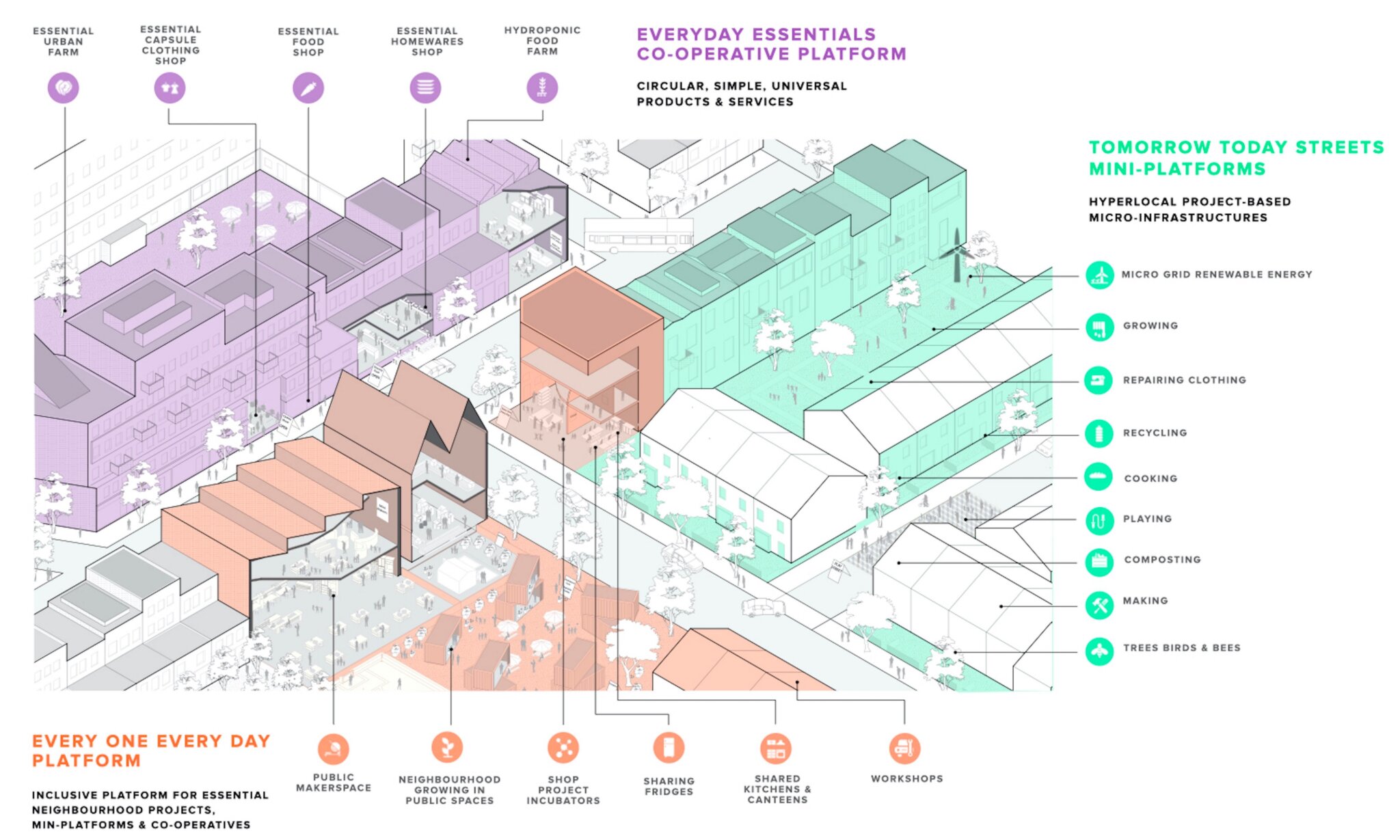

Seeing these effects and examples, and the large potential that exists for the local use of more-locally produced textiles, including the now often discarded secondary class wools, a case for a different use of these textile inputs arises. Relocalizing and strengthening the Icelandic textile sector, however, means both ramping up efforts towards regenerative and sustainable sheep farming as well as exploring new alternatives for regenerative fiber production. The Textile Center, located in one of Iceland’s largest sheep farming areas, has a unique opportunity to facilitate this process towards a regenerative textile industry, intertwining together old traditions and new innovations.

In order to create the necessary insight into the current status quo for Icelandic wool, and to see where opportunities for innovation and creation are located, we mapped the current wool value chain across Iceland, highlighting both existing challenges as well as best practices.

Check out the mapping presentation here.

Reflections

Environmental challenges, market demand for non-wool fibers and international competition put a limit to the size of the wool producing sector. Expecting wool to be a fully fledged replacement for all needed textiles in the Icelandic market would be a pipe dream. However, utilizing wool waste and combining wool with innovative bio-based materials such as seaweed, together with better reuse and recycling patterns and for example improved regulation on which types of textiles could enter and exit Iceland, would already improve the current situation. Imagine a situation where only textiles are imported which have high-quality, long-lasting and well-recyclable materials, which are then recycled within Iceland and used as long as possible in tandem with local wool and other fiber products, without being exported. Finally, consumer demand could be more generally reduced by implementing education or awareness campaigns, or hackathons involving citizens in the existing knowledge on problems and opportunities surrounding the textile cycles within Iceland.

The Textile Center, as the only textile-focussed makerspace in Iceland will play an important role in bringing together stakeholders, resources and ideas towards a regenerative fiber economy. During the remainder of the CENTRINNO project, we will take a deeper look into these opportunities, focussing on research and collaboration and the development of textile programs with partnering universities and adult learning centers.

?

??Check out the article and the interactive maps on the cartography site!

?

Interesting reads

McKinsey, Scaling textile recycling in Europe—turning waste into value.

McKinsey, Closing the loop: Increasing fashion circularity in California

Wageningen University, Recycling options for non-wearable textiles