BLOG

The power of mapping for historic urban areas

The power of mapping for historic urban areas

Reflections of the first clustering activity between CENTRINNO, T-Factor, and Hub-In

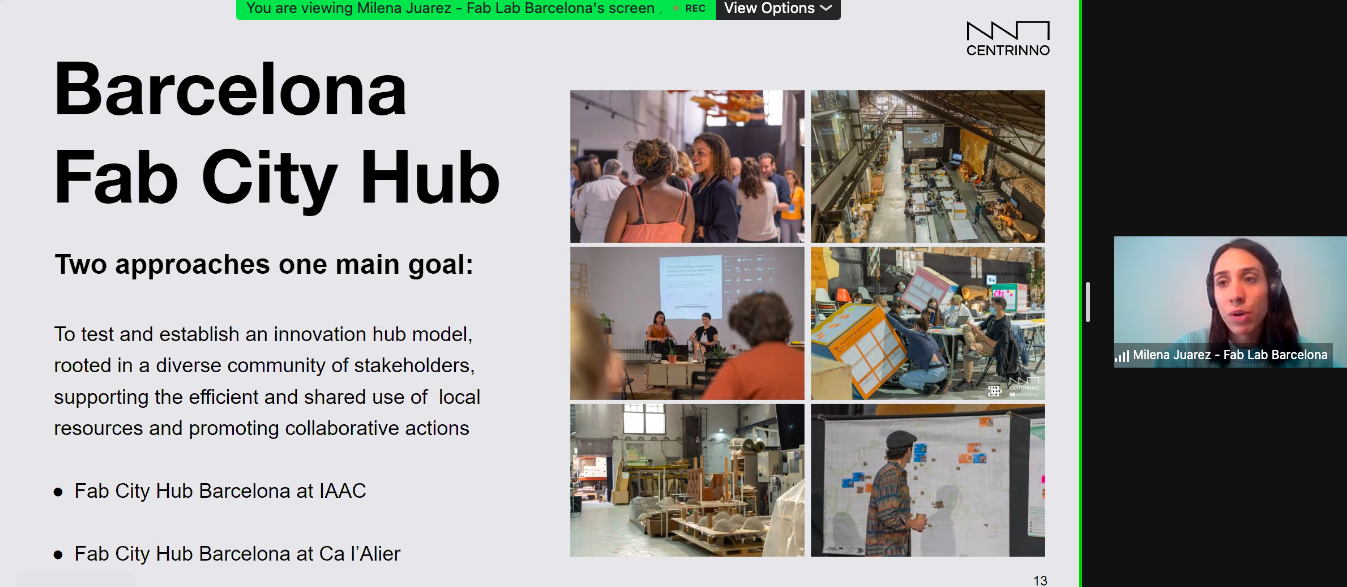

In CENTRINNO we are exploring how historic urban areas across Europe can be transformed and regenerated in a sustainable, socially responsible, and place-sensitive way. We are not alone on this journey: our sister project T-factor and Hub-In both work towards a similar mission. At the core of our joint mission lies a focus on innovation, entrepreneurship, cultural heritage, and sustainability in the development of regeneration pathways for historic urban places. To share our approaches, insights, and challenges, CENTRINNO, Hub-In, and T-Factor regularly organize clustering events, each focussing on a cross-cutting topic of interest.

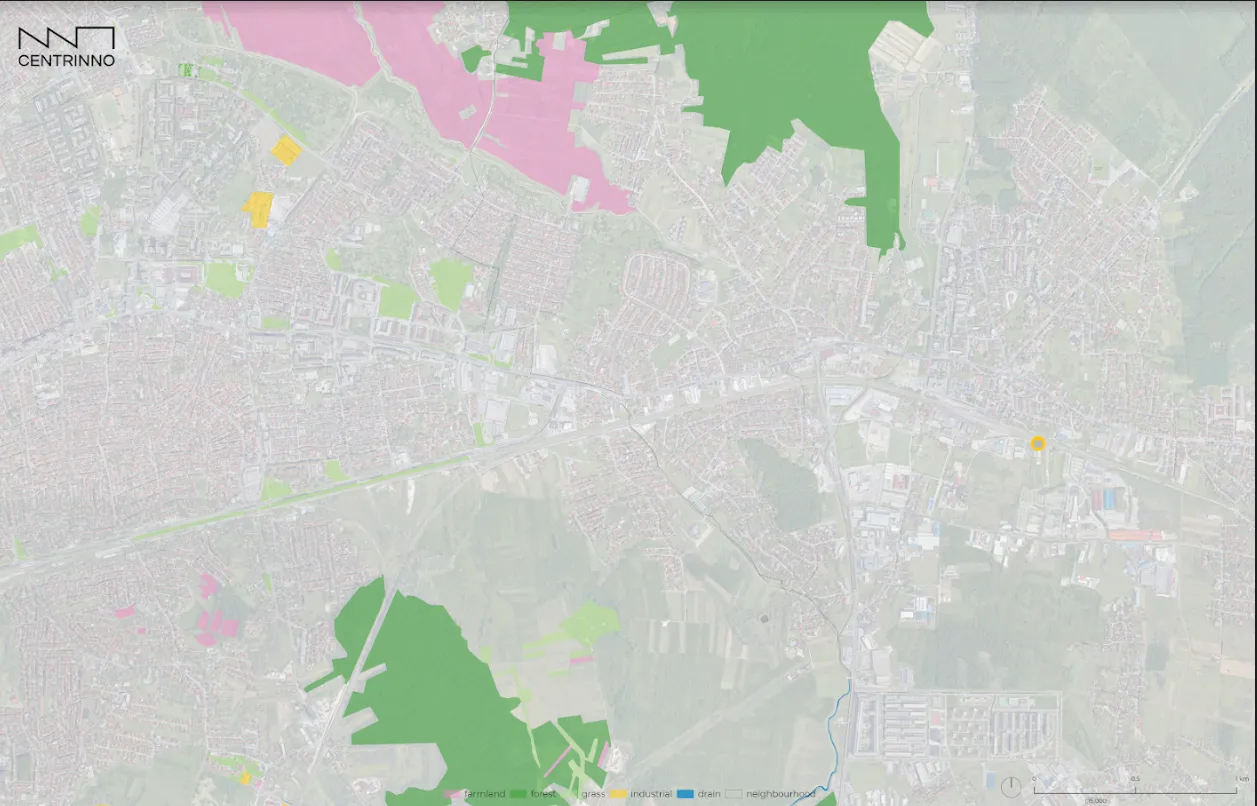

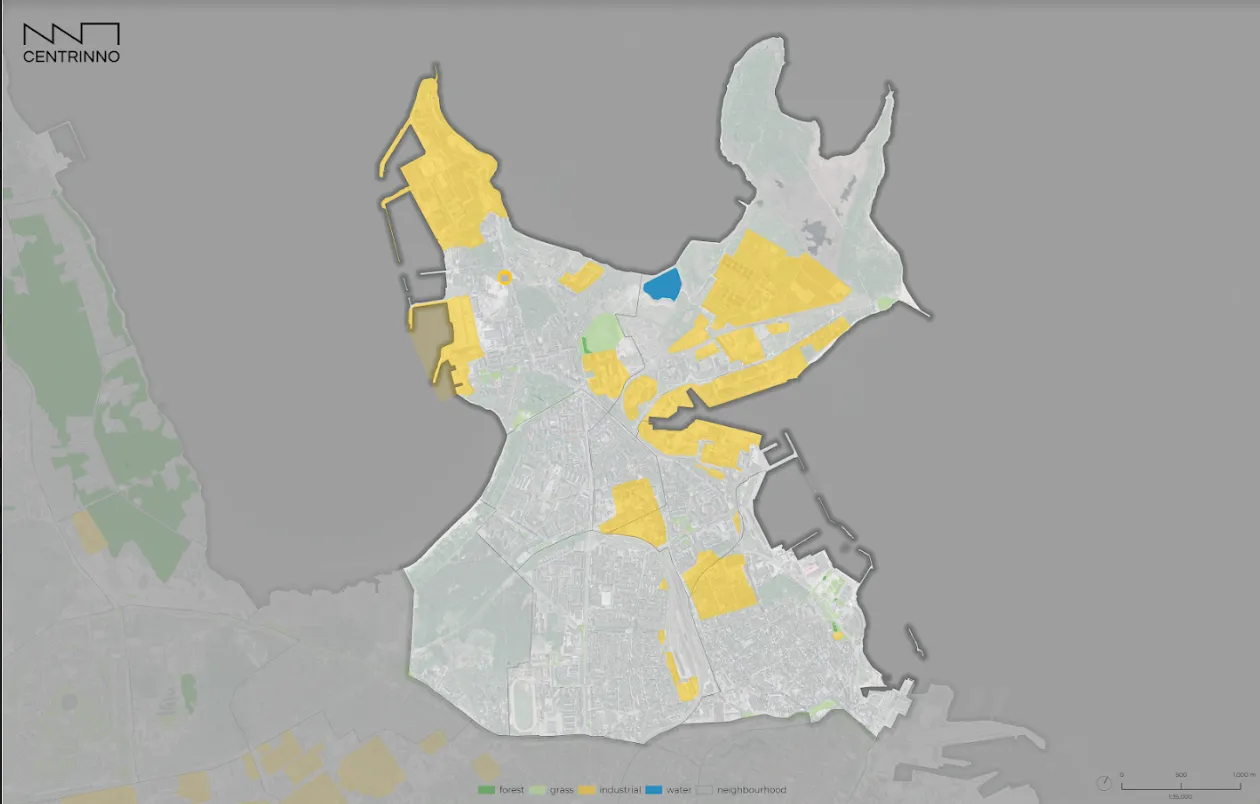

The first of these clustering workshops revolved around the following question: How can we build collective intelligence on the local urban ecosystem that historic urban areas are embedded in? Whether we talk about an industrial site, a historic city center, or a soon-to-be developed “meanwhile” open spaces – they all have one thing in common: They are embedded in a complex urban ecosystem that is shaped by social, political, ecological, and economic processes. If we agree that urban regeneration of historic spaces should be rooted in a place and its community, we need to find ways to learn about the complex context, potentials, and challenges of the places we work in.

Mapping as a tool to tell a story about the “unseen”

Mapping urban ecosystems, their local resources, and networks plays an important role in building that place-based understanding. It is a powerful approach to uncover challenges, potentials, and site-specific conditions that exist in historic urban areas. The map as a physical result of mapping is a story-telling tool which allows us to understand a place from a different perspective, and opens up our understanding about the geospatial relationship within complex urban systems.

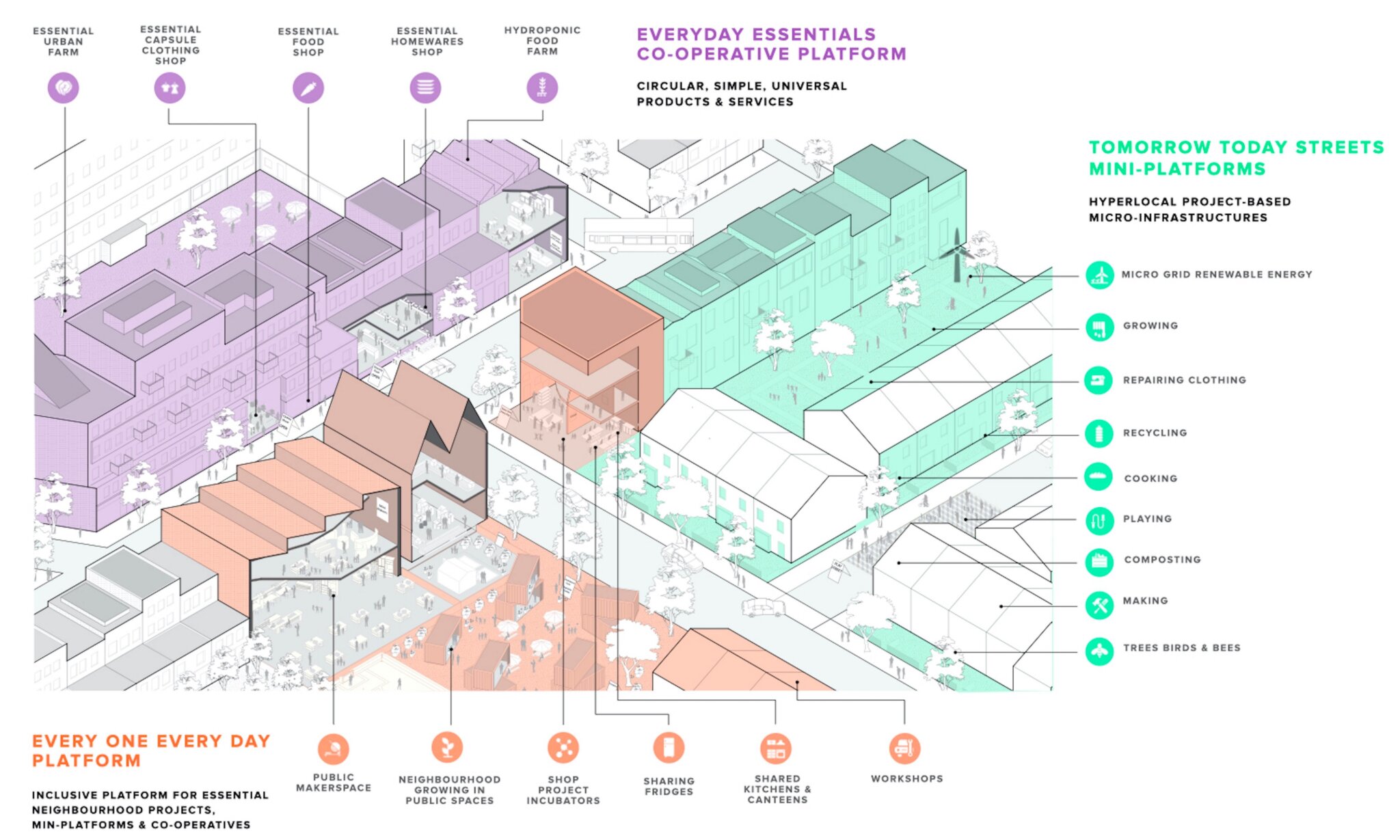

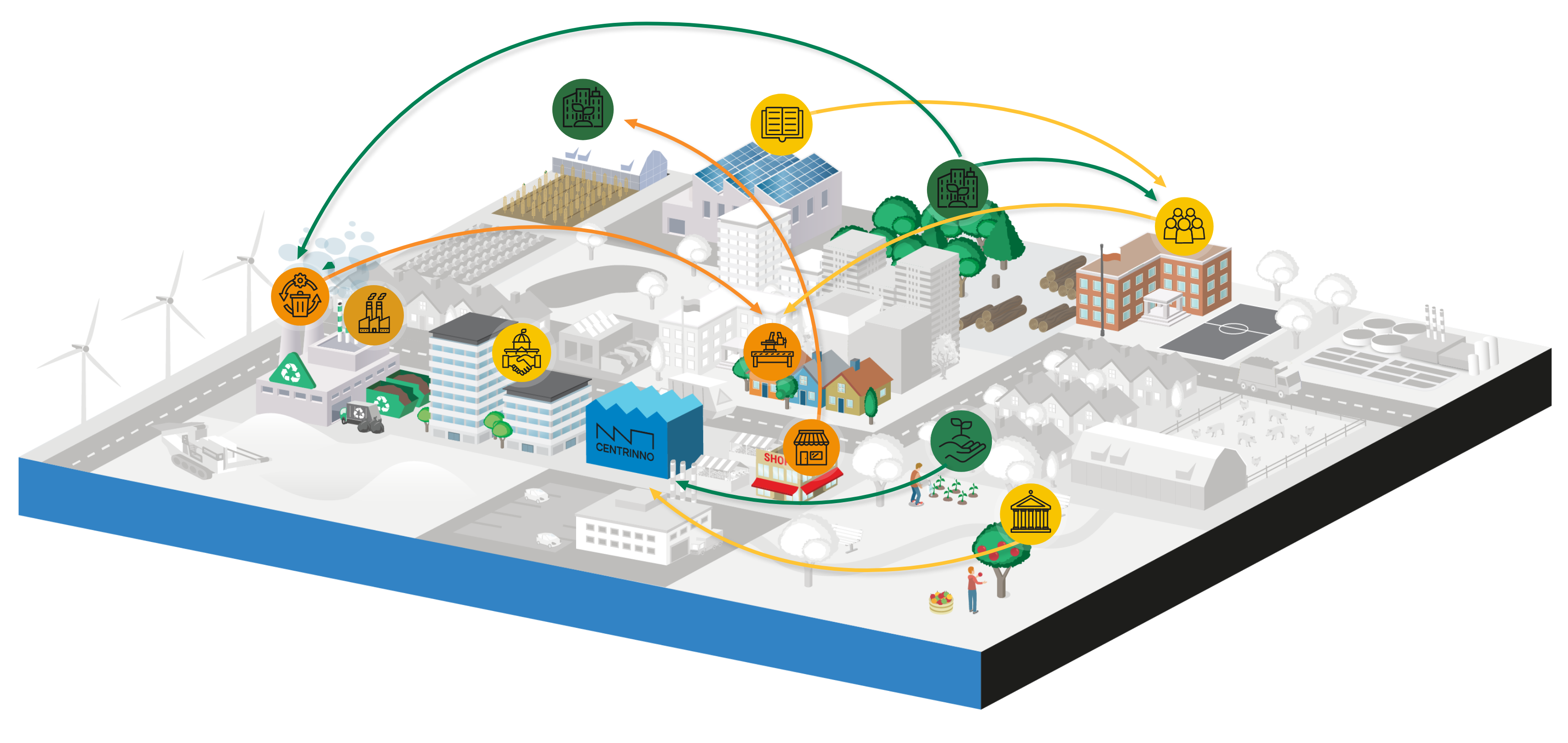

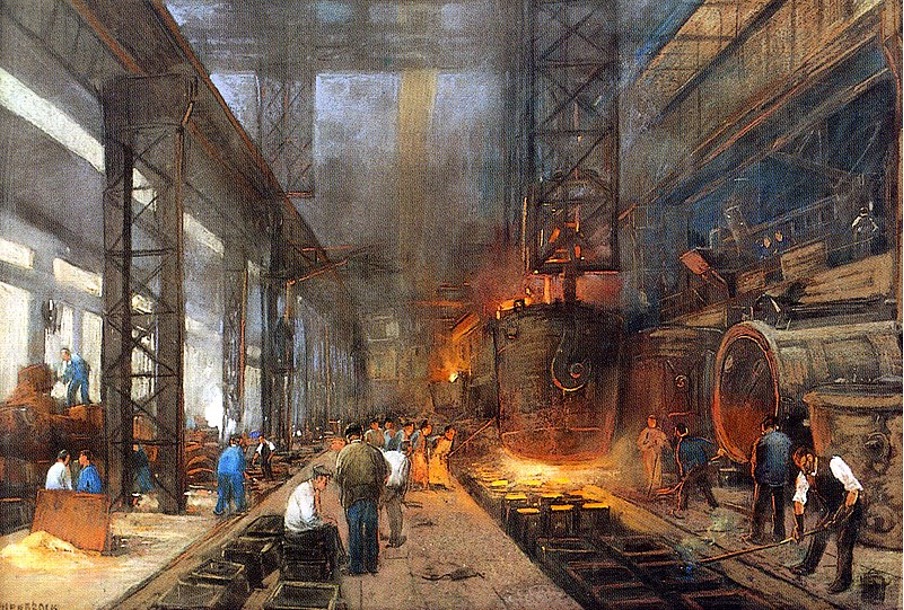

In the context of the regeneration of historic urban areas, mapping can capture the hidden value of resources present around post-industrial and historic areas. This allows us to leverage these resources to drive innovation in local networks of makers, SMEs and entrepreneurs and work towards new urban economies. To date, many resources abundant in and around historic urban areas are not used at their full potential: Waste material from urban industries are incinerated despite their potential to feed into a circular economy. Knowledge on craftsmanship and making is gradually disappearing without recognizing the social, cultural, and ecological value that it provides. Abandoned sites and temporarily vacant lots are undervalued despite the services that they provide for biodiversity, community cohesion, or urban climate regulation. From temporary community gardens populating vacant plots to abandoned buildings that become the canvas for artistic expression – interim spaces in ever-evolving and developing cities are valuable niches for social experimentation and innovation. Mapping these underused and undervalued resources means uncovering and raising awareness about “what is there”. It enables us to ground urban regeneration practices in the potentials and existing relationships that reside in a place, community, or neighbourhood.

Social, economic, cultural, and environmental challenges and needs faced by historic urban areas are equally important to consider in urban regeneration initiatives. Failing to understand and consider these challenges when regenerating neighbourhoods can quickly backlash in unintended consequences. Gentrification, displacement, and social exclusion are amongst the most dreaded phenomena. Mapping geospatial indicators across ecological, social, and economic dimensions empowers us to see more clearly how local challenges are manifested in an area, how they are interconnected, and how we can address them.

Maybe one of the most famous maps is John Snow’s cholera outbreak map that was at least partially responsible for identifying the root cause of London’s severe health crisis in the 19th century. With advanced geospatial analysis tools our abilityto make sense of complex geographical data hasexpanded drastically. We can tell a story about how urban green space investments trigger increases in housing prices. We can show if the burden of noise, waste disposal, environmental pollution or lacking services are disproportionately carried between different communities around urban areas. Or how changes in land use zones cater to the needs of residents in historic neighbourhoods. While there is no one approach to how mapping can solve these questions, the “art and science of map making” can help us make complex information more accessible and thus, assist a more sustainable future development.

CENTRINNO, Hub-In, and T-Factor have created tools and approaches throughout their project duration that make use of the power of maps and mapping. To learn more about these tools and methods, regularly check our project’s resource section where we publish detailed descriptions of our mapping approaches.

Planting the seed for urban transformation

Despite the power of mapping, our joint discussion between the three sister projects has led to a critical point: Mapping alone does not trigger positive change towards inclusive, circular and sustainable urban transformation. It may provide a fruitful starting point to inform and guide urban regeneration activities. But how do we ensure the insights of mapping and maps translate into more intelligent practices? Our discussion led to three key insights that merit further exploration throughout our projects.

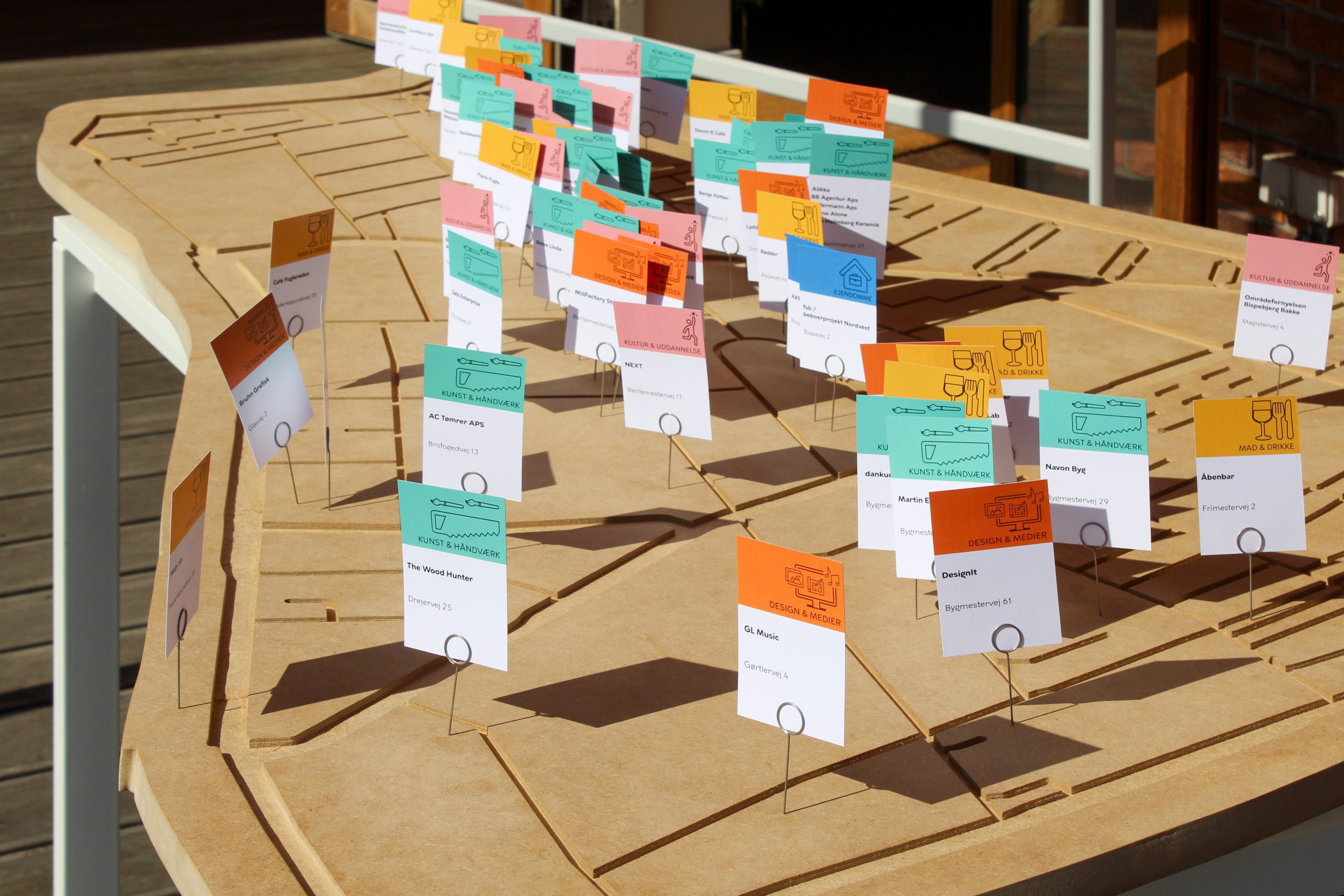

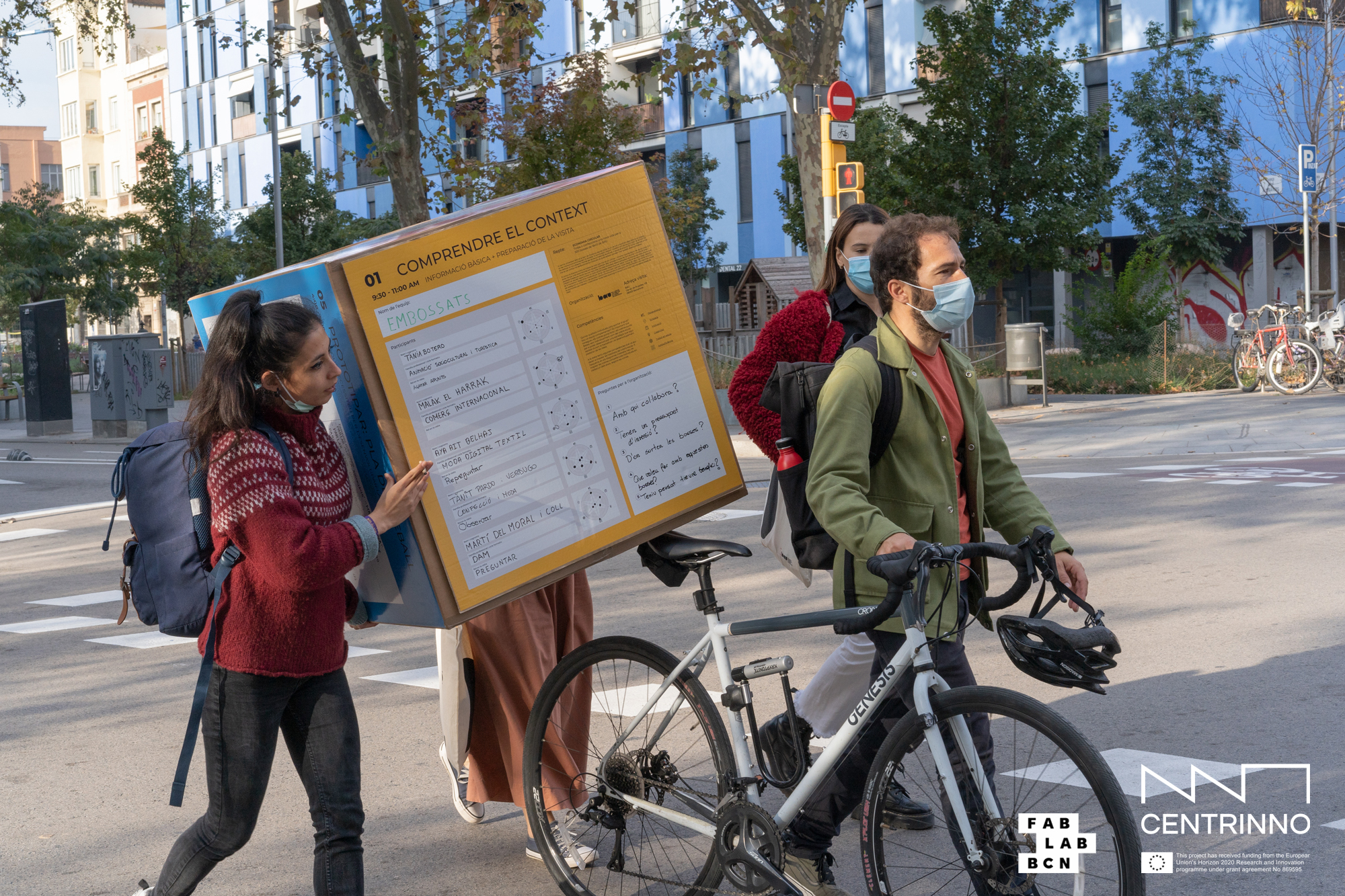

First, it is important to consider mapping as a process rather than a means to an end. Indeed, the physical or digital map as a result of advanced geospatial data collection and processing can provide a lot of valuable insights to the map user. But during our clustering event, the participatory nature of mapping as a process is equally important. If we understand mapping as an iterative process of geospatial inquiry driven by the local community, we ensure a shared sense of ownership about data and the resulting maps. Local communities and relevant stakeholders should be in the driving seat of this process since the search for spatial data on urban ecosystems, networks, and resources is where discovery and learning happens.

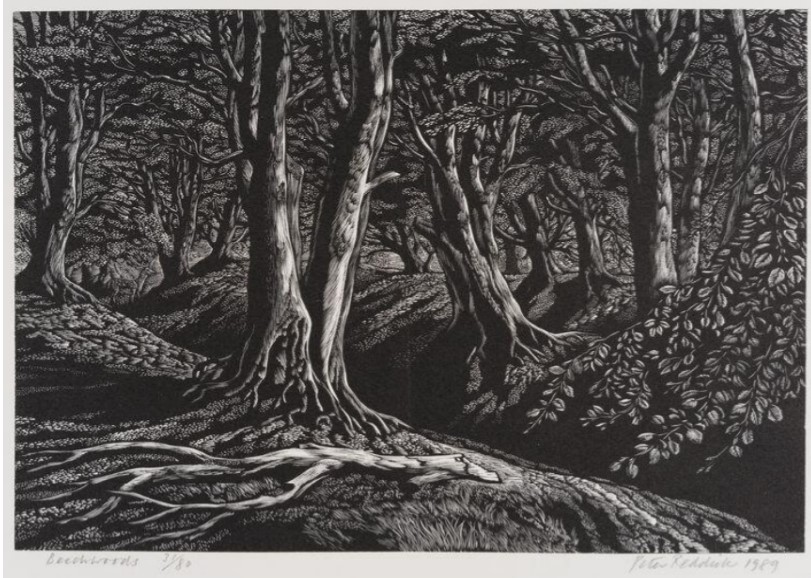

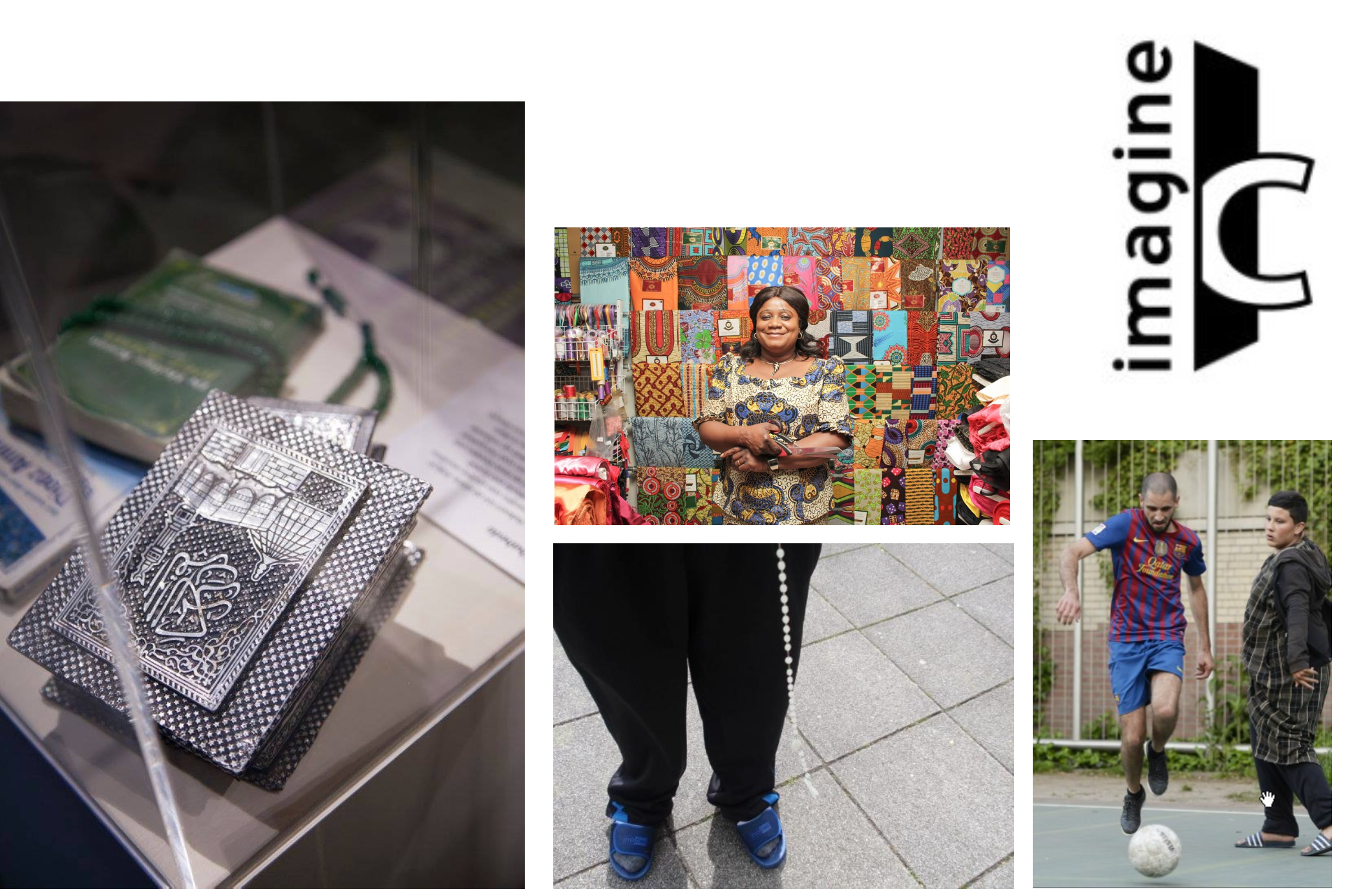

Second, our clustering discussion brought up the broad question on how we can effectively map and communicate alternative forms of non-financial value. While it is easy to map a building or site officially declared as “heritage”, it is harder to unveil the meaning these places hold for diverse community members. So how can we ensure urban redevelopment plans take into account the social, cultural, and ecological value of historic urban areas even if their preservation does not provide a direct financial benefit? How do we map the benefit vacant lots can have as spaces for social and cultural experimentation, or the tranquility an abandoned area, reclaimed by nature, can provide?

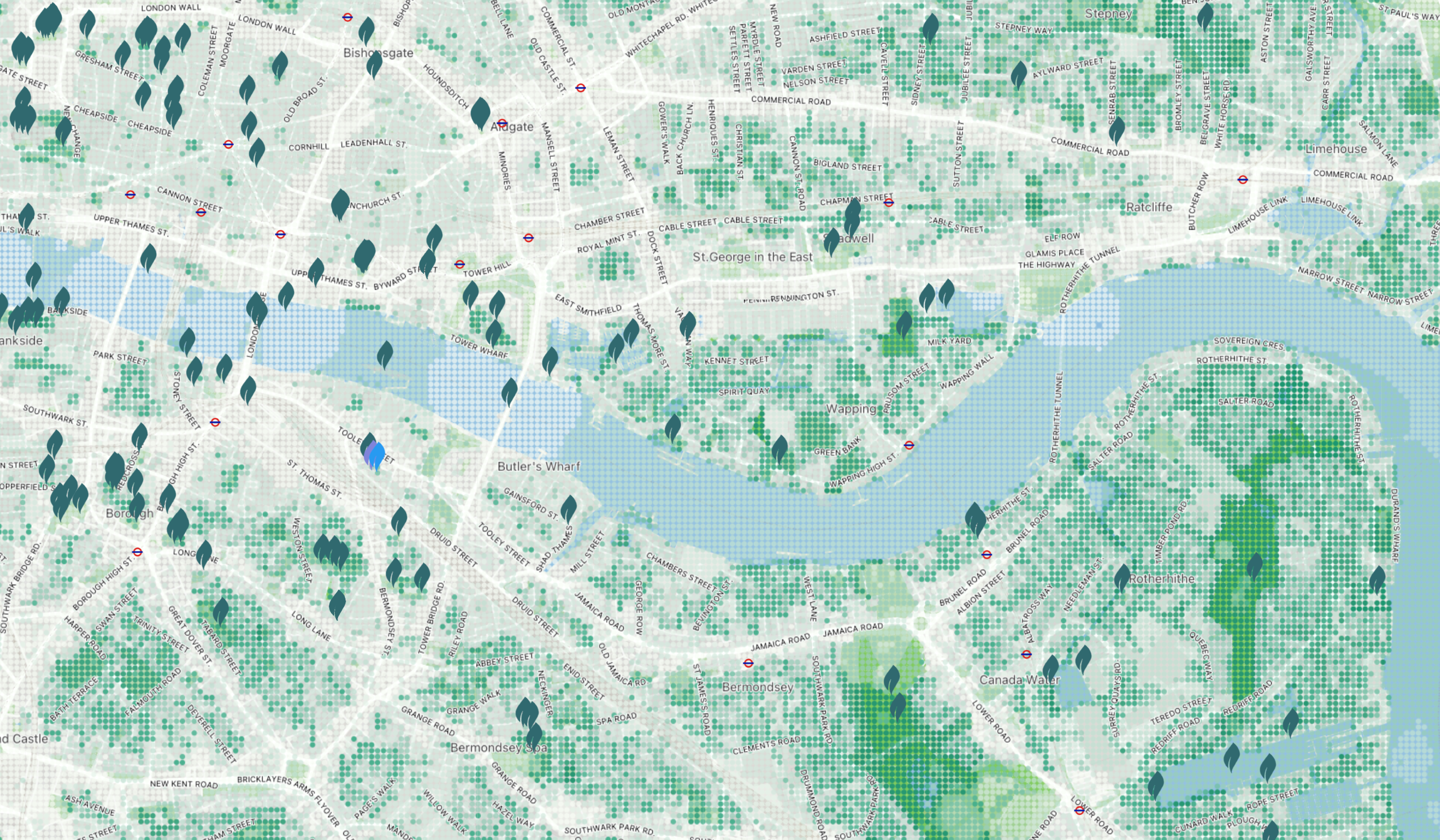

How do we map the value of quiet and restorative places? – Credits to Tranquil Pavement London

This question is even more critical since cultural and social values imbued in urban spaces can significantly differ between newcomers and locals; between older and younger populations; and between groups with diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. Through our sister projects, we are seeking to develop mapping approaches that respond to the needs and viewpoints of diverse communities inhabiting historical neighborhoods. As an example, CENTRINNO’s planned Living Archive aims to address these challenges. The Living Archive will become an online repository that will host different stories, memories, and anecdotes hidden behind historic places, items, and traditions. Uncovering these stories behind the cartographic map of the city can become one way to do justice to the diversity of perspectives and values held by local communities.

Lastly, to leap from mapping to action, we need to build both mapping capacity, as well map-reading “literacy”. Participatory mapping of communities and their assets is not new, and a well established tool for sustainable development. But with the shift to digital mapping approaches, cities need a new skill set of searching, organizing, and analysing geospatial data. Especially in smaller towns GIS analysts are not always available to drive local mapping processes. Simultaneously, using, reading and interpreting digital mapping tools that engage the local community also requires a certain level of digital literacy that not all residents bring with them. Digital interactive maps that allow users to feed in geospatial information about their community can “democratize information” and crowdsource the collective intelligence about a place. But they cannot work in isolation. One possible way to increase the social inclusivity of participatory mapping in historic urban areas could be to fluidly integrate digital mapping tools in “offline” community activities. Mappina – a community of “mappers” that create alternative city maps – does exactly that: While the majority of mapping is done via mobile technologies, regular community events on reclaiming and co-designing urban spaces, and urban mapping workshops complement the initiative. In the coming months we will explore how T-Factor, Hub-in, and CENTRINNO can integrate these approaches into our mapping activities.

DIPAS (digital participation systems) showcases another innovative way to integrate digital mapping tools with onsite engagement between expert planners and citizens. HafenCity GmbH / Thomas Hampel

Building a joint mapping task force across our sister projects

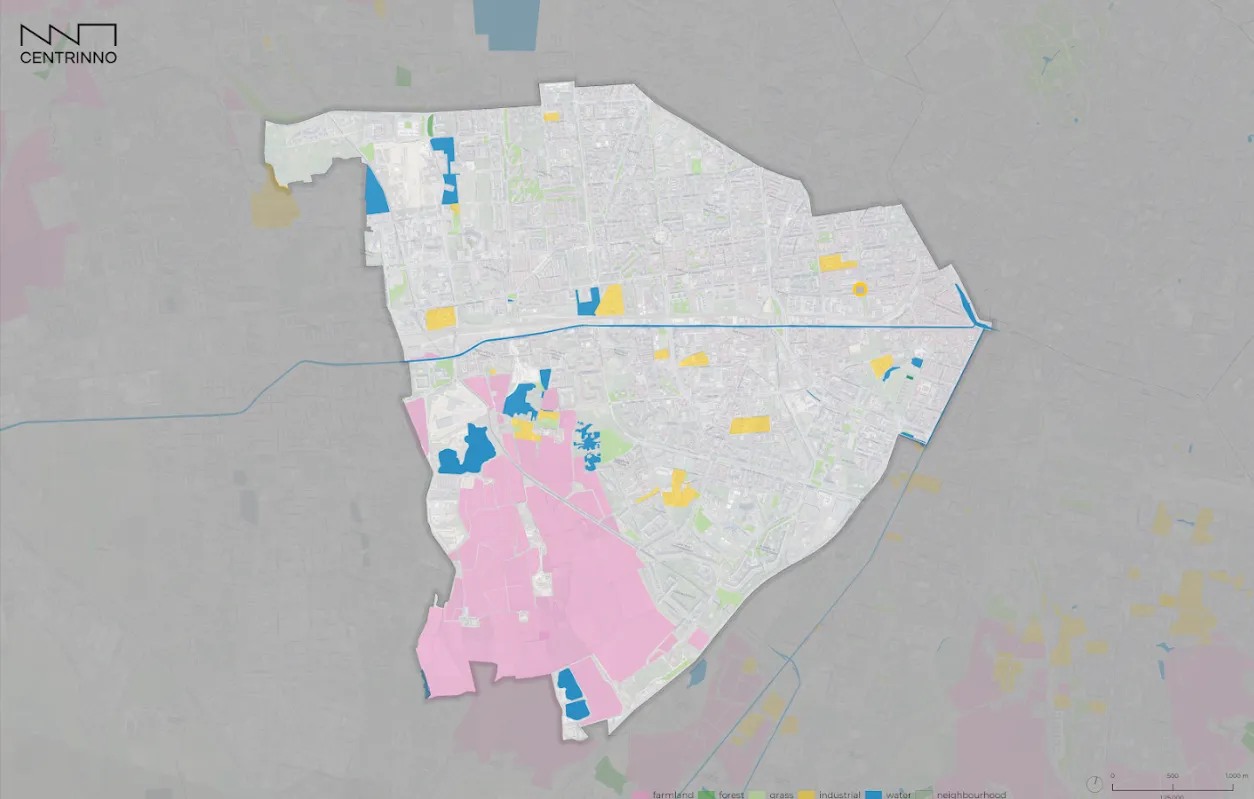

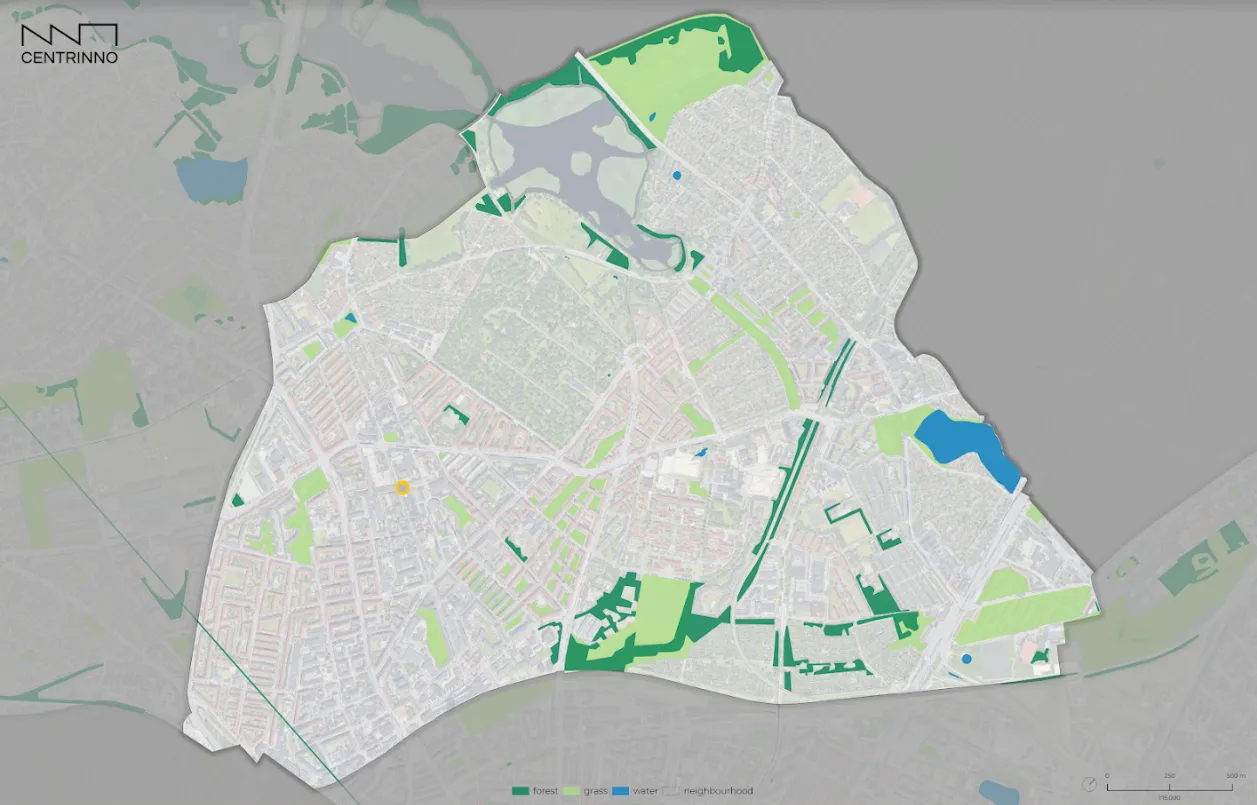

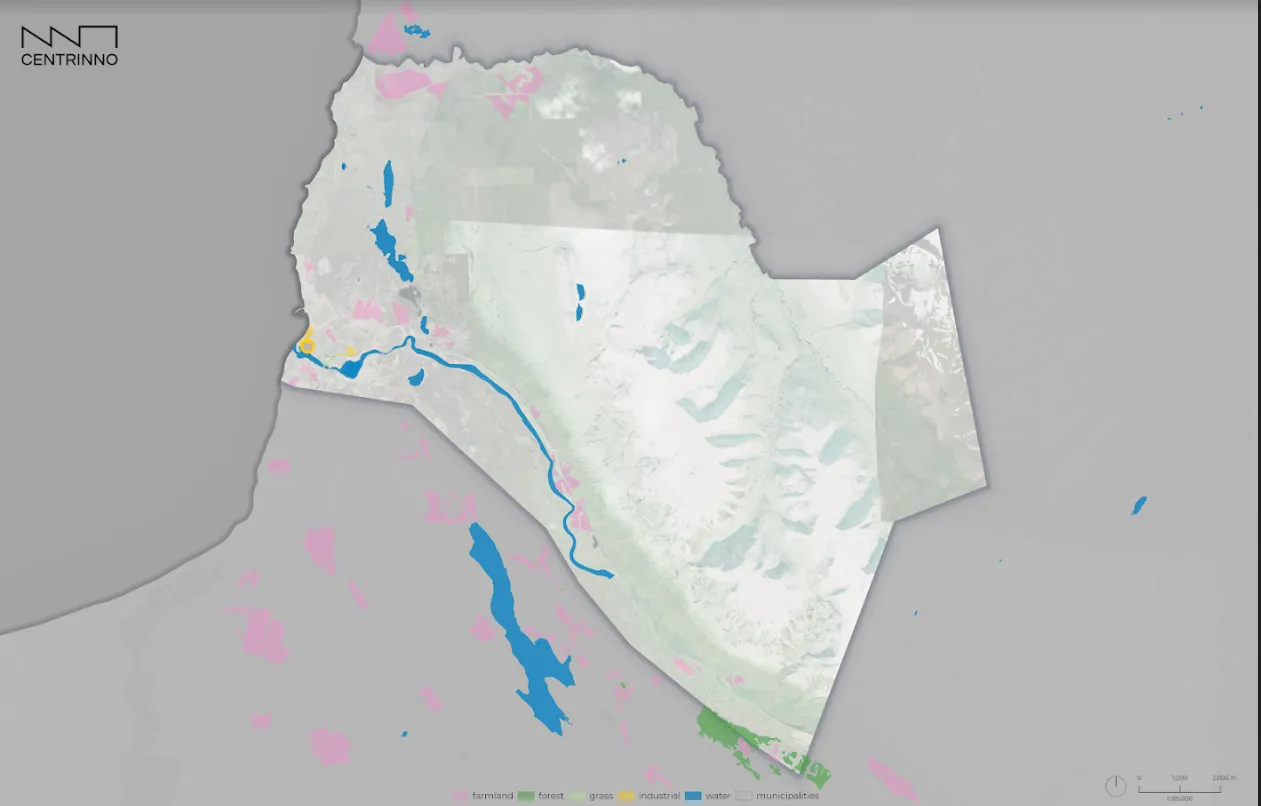

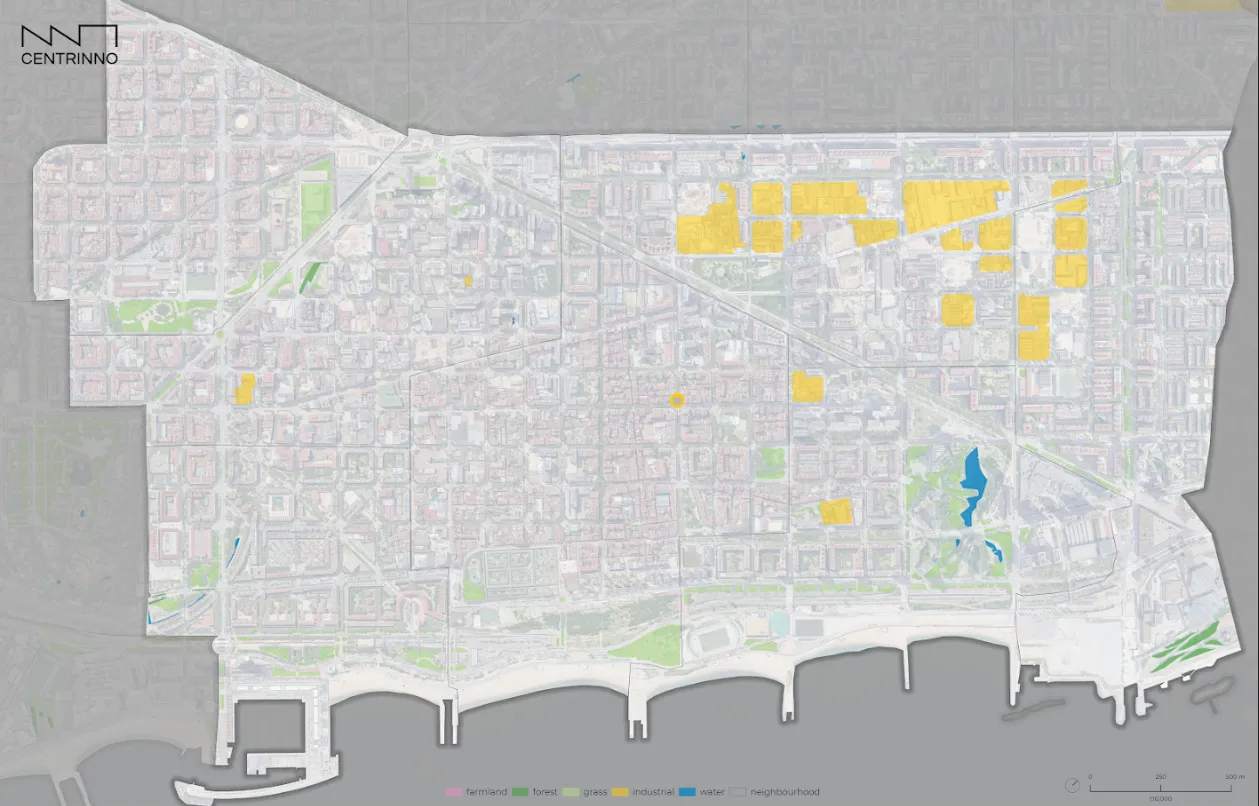

During the coming years, the three sister projects will each develop their own version of an online mapping tool. These tools should raise awareness about resources in Europe’s historic, post-industrial and meanwhile areas. They should help us build collective narratives for these spaces, and spark the creation of stronger and inclusive networks for local innovation.

Whilst different in the purpose and functionality of these tools, we do see the need to continue exploring potential synergies and learning opportunities between each of our projects. Can we learn from each other how to build capacity for urban mapping projects in local communities? On how to build interactive, yet easy-to-use mapping tools with a legacy that reaches beyond our projects’ duration?

To keep this discussion going, we will establish a mapping task force, chaired by people from each sister project, where we explore these questions and potentials for collaboration. So stay tuned for more mapping insights!

Learn more about our sister projects

| T-Factor – Context Mapping:

“T-Factor’s mission is to boost radical new approaches to urban regeneration, focussing on the key role that meanwhile spaces can play in unleashing inclusive, sustainable and thriving urban areas. Through context mapping, T-Factor aims to display initiatives across Europe. This interactive map provides background knowledge of the initiative and thus supporting pilots in a broader context […] In the project, we work across different regeneration initiatives in Europe and beyond, developing an international platform of ‘meanwhile’ city-making support, mentoring and knowledge exchange. Leveraging international collaboration, we aim to build a full portfolio of tested innovations embracing design, organisation, management, governance, funding and regulatory aspects of meanwhile spaces-” – T-Factor “HUB-IN aims to foster innovation and entrepreneurship in Historic Urban Areas (HUA), while preserving the unique identity of the historic sites regarding their natural, cultural and social values. HUB-IN will utilize geospatial data to visualize and manage local innovation ecosystem in order to facilitate the diagnosis of HUA. This is therefore supporting the implementation of the Action plan activities of the pilot cities.[…] innovation and entrepreneurship as the main drivers of urban regeneration in HUAs.” Hub-In |