BLOG

Creating a circular hub at the ZIC site

Creating a circular hub at the ZIC site

Creating a circular hub at the ZIC site

The ZIC – an actor for circular transformation?

Words by Metabolic, Ressources Urbaines RU & On l’fait OLF

ABOUT THE PILOT AREA

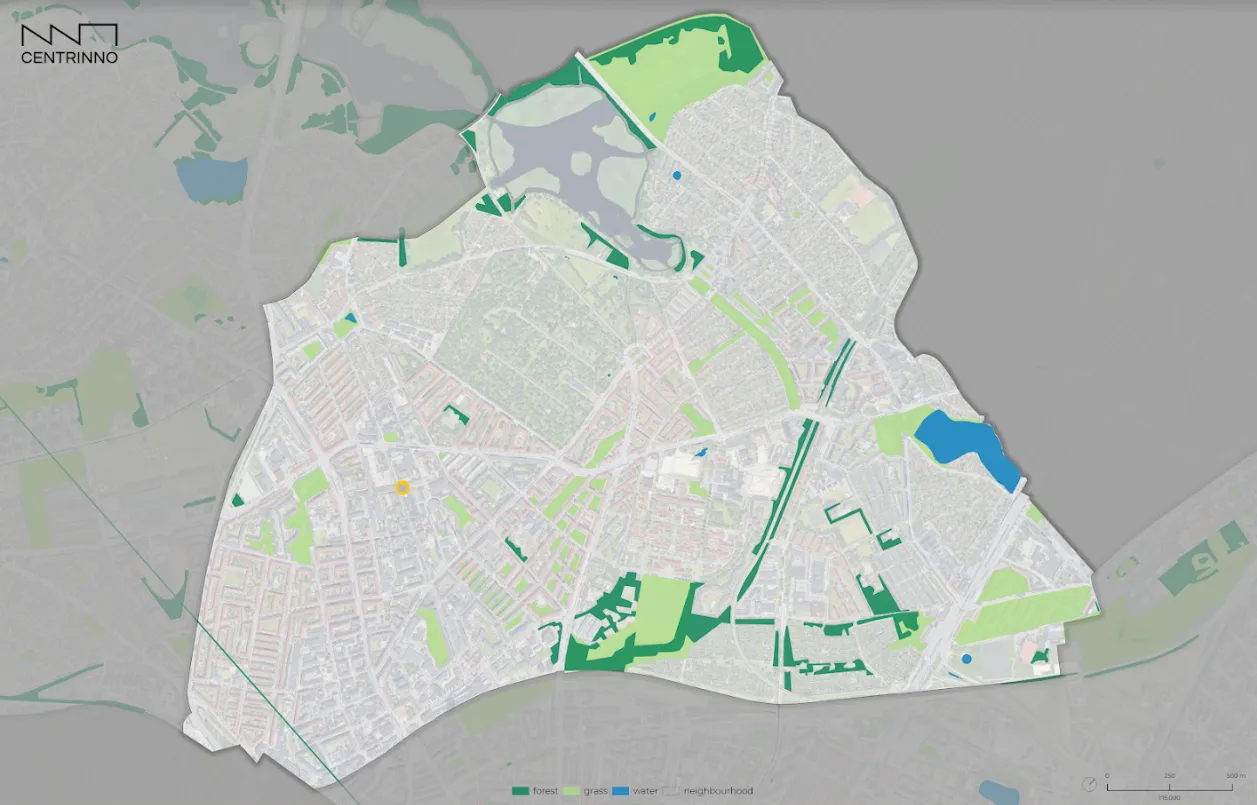

Pilot area: ZIC Zone Industrielle des Charmilles

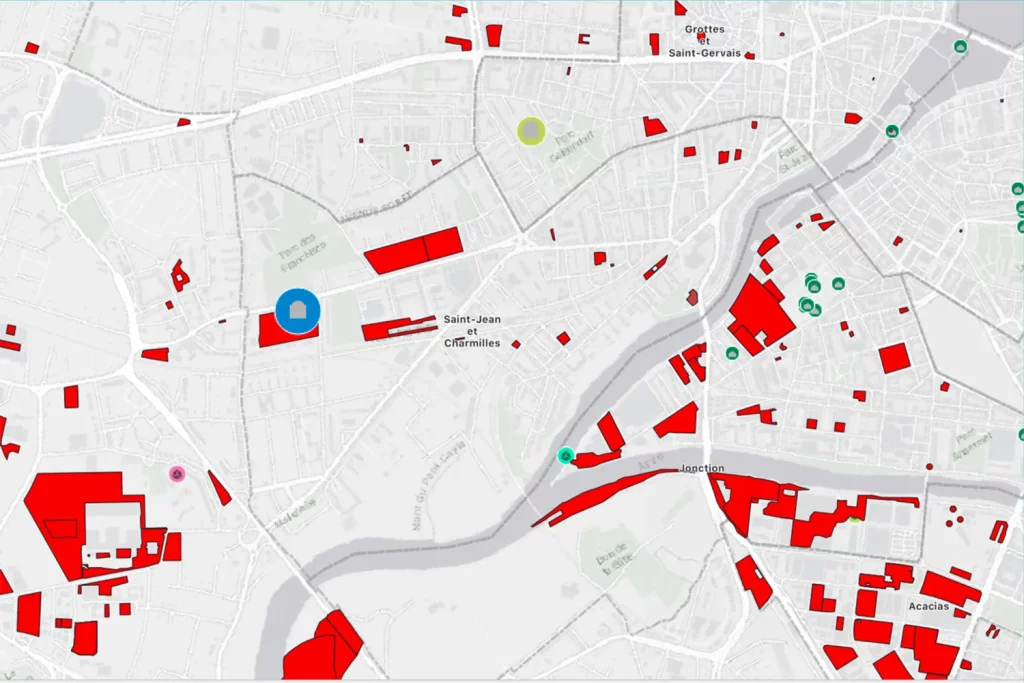

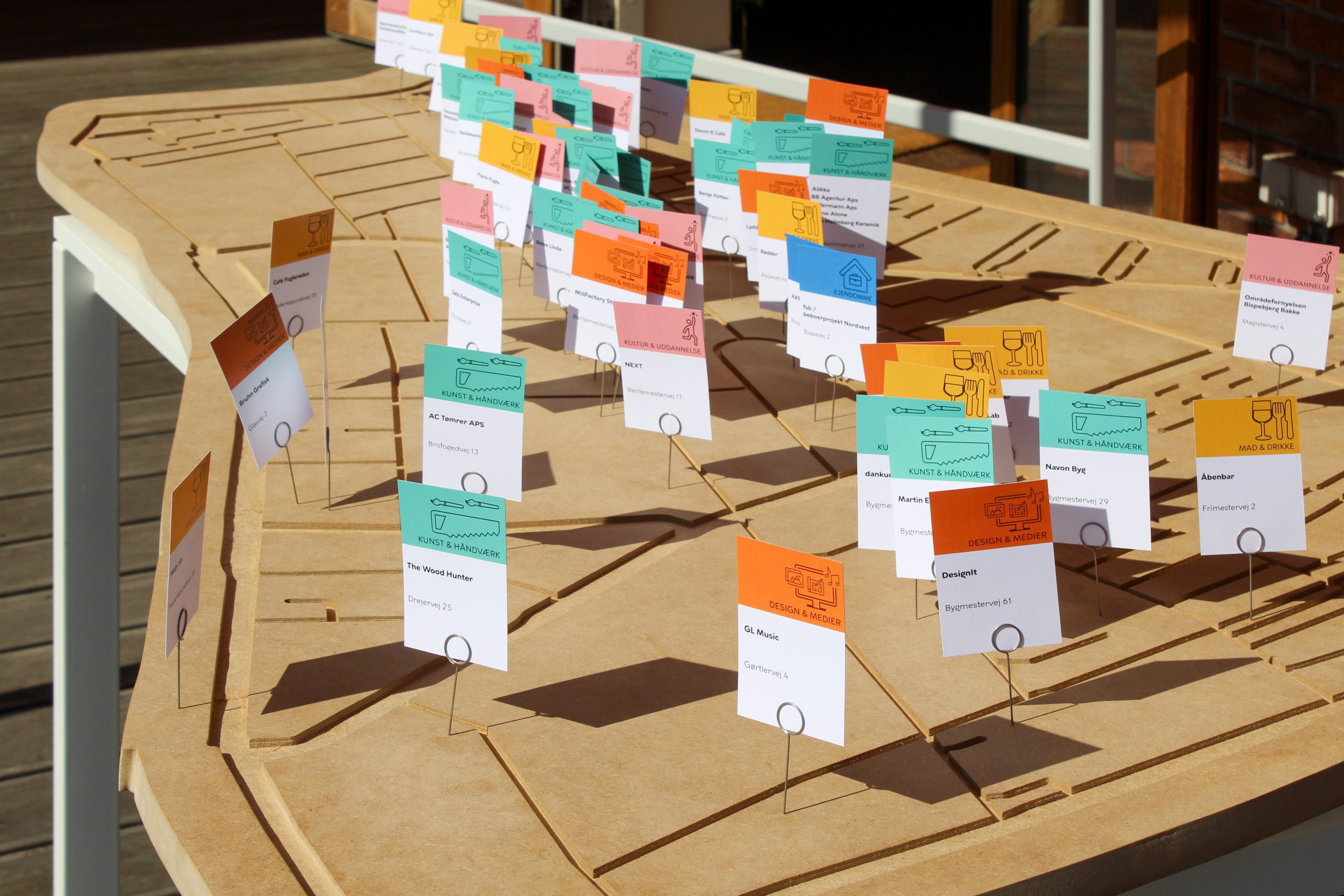

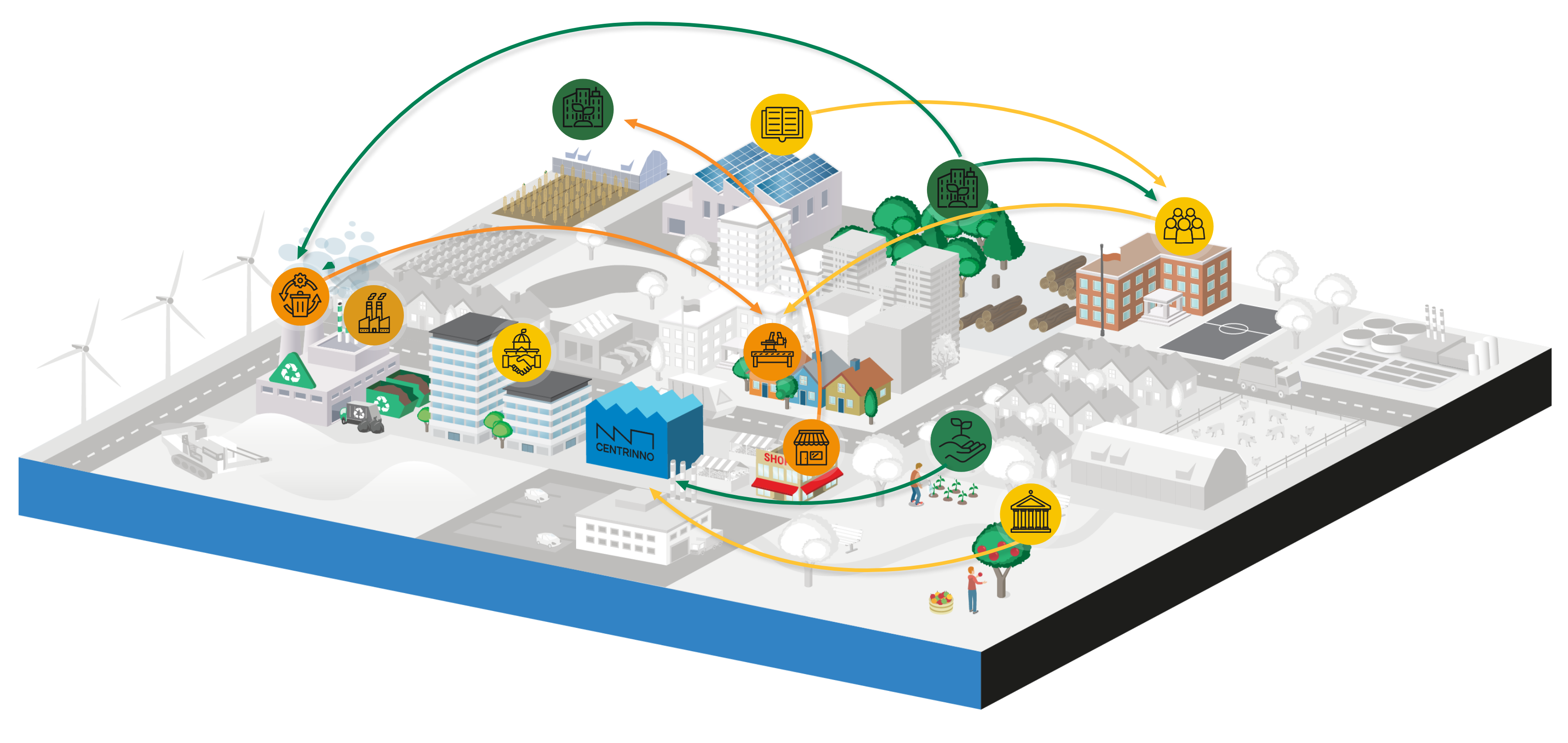

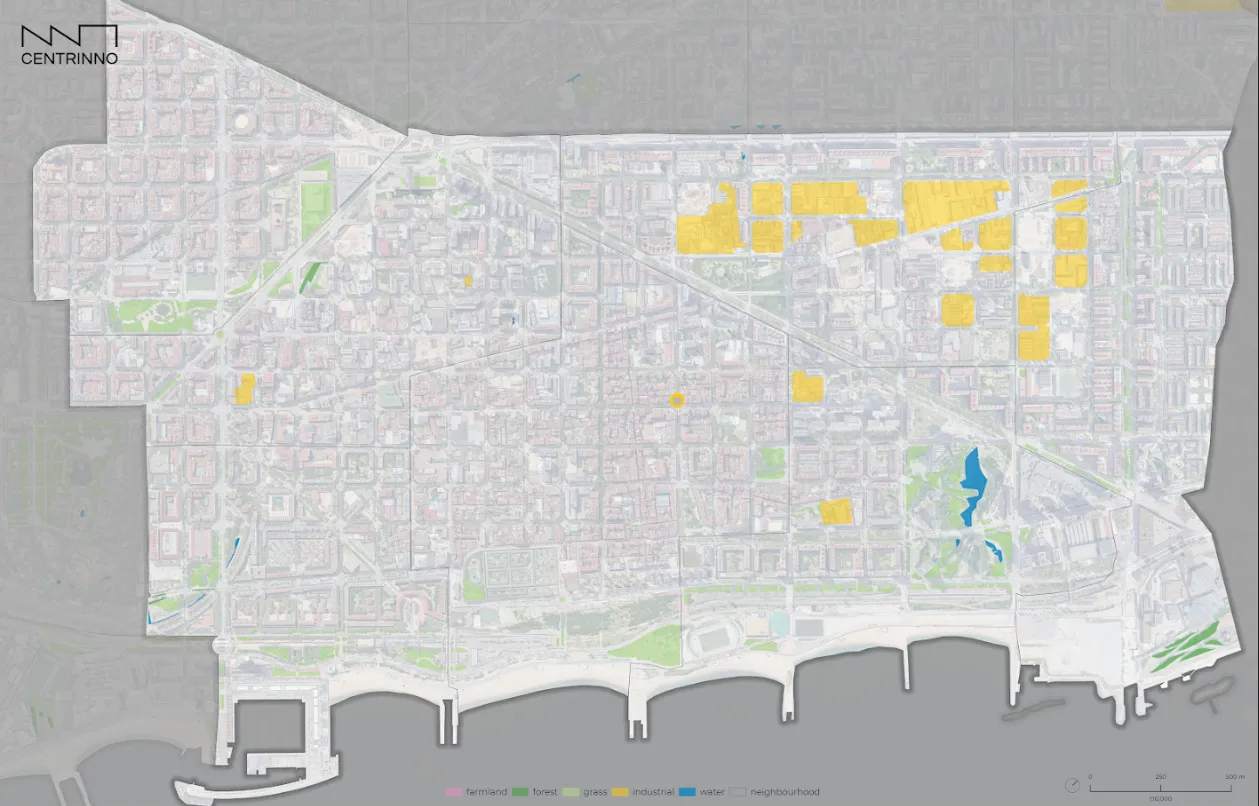

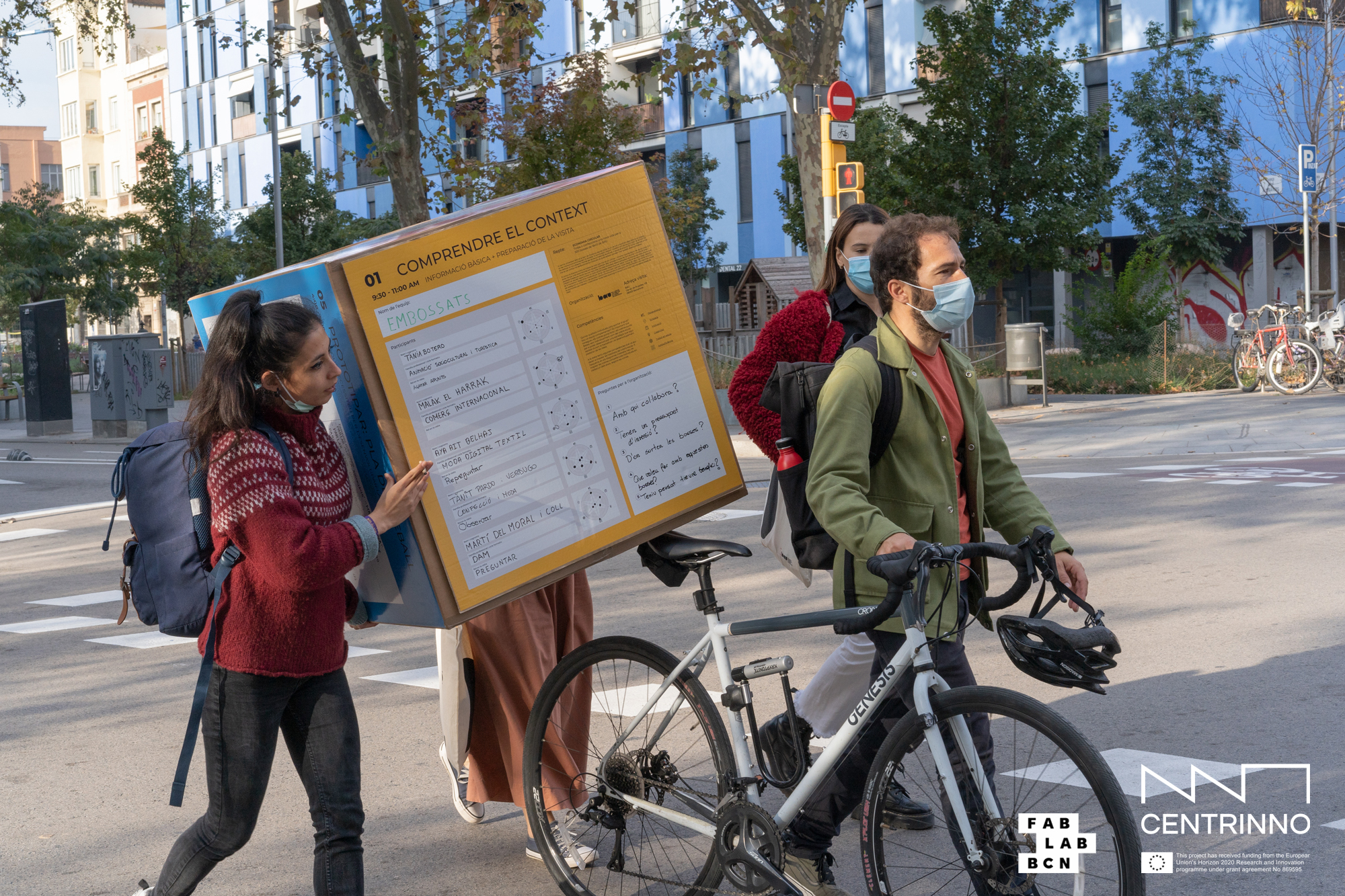

Led by Ressources Urbaines RU and Onl’fait OLF, the Geneva pilot team created a detailed cartography of the the local makers, craftspeople, artists and businesses currently active around the Manufacture Collaborative MACO hub in the Zone Industrielle des Charmilles – or ‘ZIC’. By mapping and interviewing local ZIC stakeholders on their resources, the pilot team identified several available material resources that could be integrated in a circular value chain. Next to the detailed inventory of local makers, our pilot team has also mapped the city-wide flows of construction waste to understand how the makers of the ZIC can tap into and contribute to a more circular economy at a city-scale.

Building bridges and closing loops with wood (waste)

The Zone Industrielle des Charmilles – in short ZIC – is the last standing large industrial zone within the City of Geneva. Located in Charmilles, a neighborhood characterized by major development projects, the ZIC is home to a diverse mix of traditional craftspeople, small businesses, artists, architects, designers, innovative and cultural organizations co-existing on the site. Materials like wood, metal and concrete are as much part of the ZIC as digital technologies, innovation and the dissemination of culture. It is a place where traditional craft thrives, new products are made, materials are reused and maker skills are taught. Especially as cities across the world move towards the circularization of their production and consumption processes, keeping these artisanal spaces available and avoiding the loss of diverse human capital is important.

?

With its diversity of actors that cluster resources, ideas and skills in one spot, the CENTRINNO pilot in Geneva set out to understand the potential for the ZIC’s actors to contribute towards a circular economy.

Discover the ZIC and its map here.

Our journey to map circular opportunities has not been a straightforward one, encountering hurdles along the way. Tensions and gaps between the old and the new have been unveiled, between innovation and business-as-usual, which requires us to move with intention and caution. To understand how business-as-usual has transformed into the ZIC throughout the past, let us dive into this history before mapping opportunities for tomorrow.

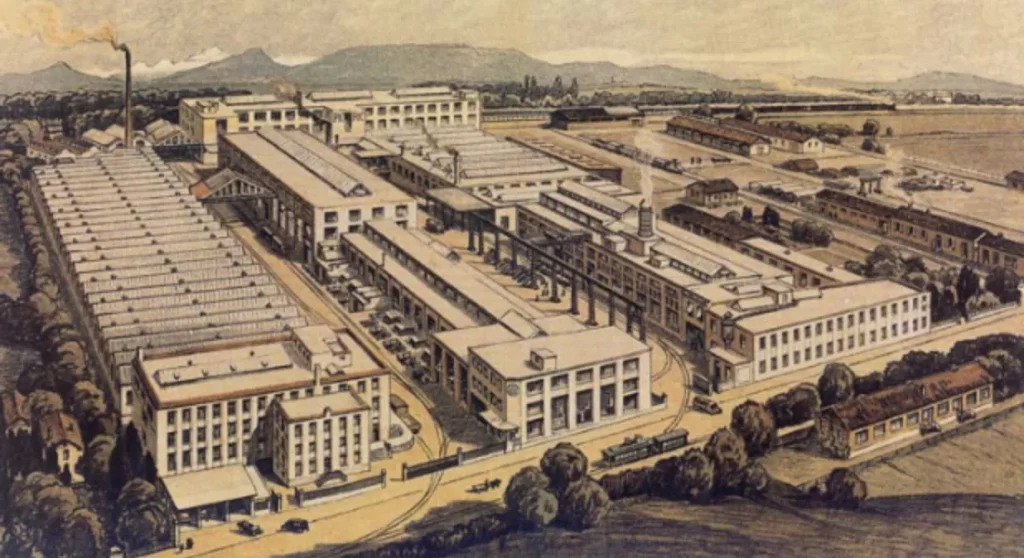

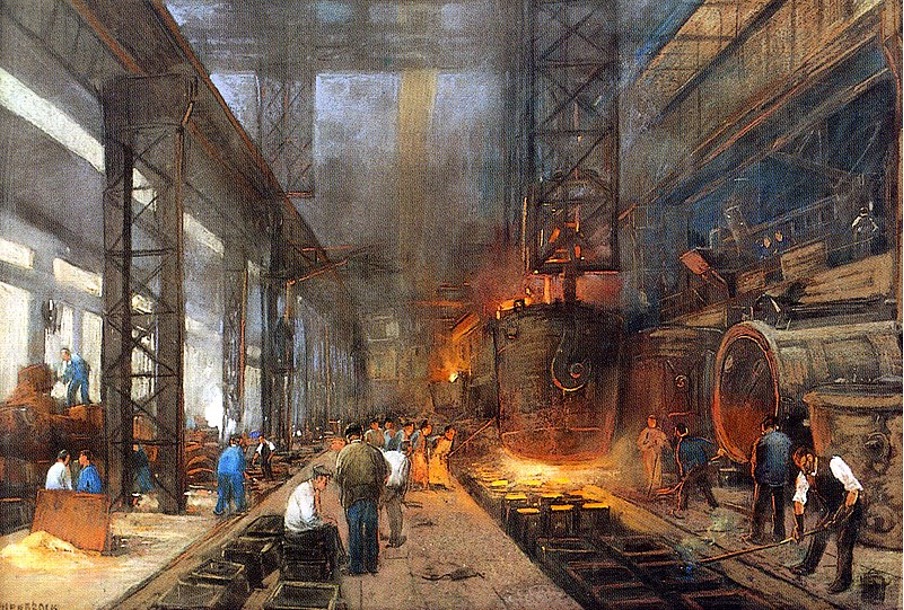

Image 1. Charmilles neighborhood around 1920. Source: RPI-Recensement du patrimoine industriel -1800 à 1975

The ZIC – between innovation and tradition

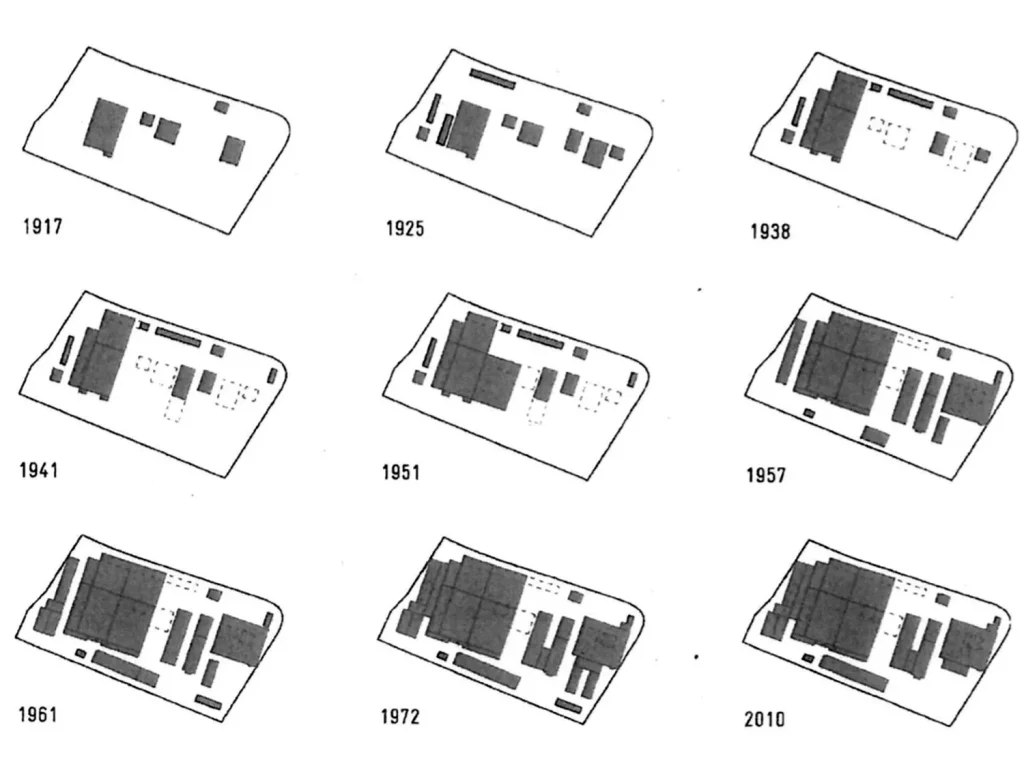

?The development of the zone started about a hundred years ago when the ‘Société des Instruments de Physique’ (SIP) needed to expand its production from its main site in the center of the city. The ZIC site – standing on the City of Geneva’s municipal boundary – was chosen, as the surrounding area “Charmilles” was a fertile ground for the implementation of new innovative industries close to the Rhone river, the city and its workforce. From 1920 to 1970 the ZIC site was developed in an incremental manner which saw many buildings being erected for the different activities of the SIP.

Image 2. Development of the SIP on the ZIC site 1917-2010. Source: Ville de Genève

From the mid-seventies to the end of the nineties, Geneva followed the global movement of de-industrialisation. This meant that many of the companies operating in the neighborhood of the “Charmilles” were either delocalised to new industrial zones further away from the city, moved abroad or went bankrupt. The SIP filed for bankruptcy in 1995. The site was subsequently bought by the municipality of the City of Geneva in 1998.

Image 3. SIP-ZIC site 1970.

Since taking ownership of the ZIC site, the municipality rented out the different spaces to a relatively diverse mix of tenants of craftsmen and small companies, relocated some artists and associations who were evicted from other sites in the city or allocated spaces to its own municipal services. In 2018, Geneva decided to find new locations for the different municipal services that were based in the ZIC with the intention of bringing new innovative programmes on site. Open calls around culture and circular economy projects were launched for these newly freed spaces. It is in this context that the project of the “Manufacture Collaborative” MACO, the planting initiative “Forêt B”, the cultural project of the “6 Toits” and the sawmill “Les 2 rivières” arrived.

Image 4. Manufacture Collaborative MACO 2021. Source: Ressources Urbaines

However, due to a lacking clear middle to long term comprehensive vision, the actual cohabitation of activities on the site has grown rather detached from each other and tensions have arisen. In effect, the initiatives taken in 2018 by the municipality to implement new programmes and give these stakeholders free spaces – meaning not paying rent but asking the stakeholder to renovate and update the spaces at their own cost – has created a landscape of suspicions where traditional craftsmen and small businesses have grown unsure of the real intentions behind the insertion of these new parties. This process of bringing in new, partly subsidized, activities tends to be perceived as a form of gentrification ignoring the currently present makers’ needs. Today the situation has grown so polarized that the association of craftsmen and small business, “ALAAZIC”, has launched a petition to put in question the policy of the municipality.

In this context, though we cannot underestimate the potential for the ZIC to become a transformative living lab for circularity and an exemplary site to demonstrate the benefits of a circular productive city, it has not yet been possible for the Geneva CENTRINNO pilots to establish a bond of trust with the existing actors in the zone and to come together with common goals and projects. However, it is important to note that most craftsmen present on the site are already attentive to the valorisation of raw production materials and waste.

Building upon the realities of local tensions and challenges, we present our ideas and opportunities of the ZIC to act as a circular accelerator with caution. We have to remain humble and asses that, albeit many opportunities for internal synergies within the bounds of the ZIC as well as between the ZIC and Geneva’s wider urban metabolism exist, the precondition for them to to be exploited and put in use is the construction of a relation of trust between the different stakeholders and the definition of common denominators.

It is our hope that wood, a commonly used material by many local craftspeople at the ZIC, does not only help to regenerate local soil but also to build a bridge between traditional craftsmanship and the newly arrived actors on site.

The ZIC as a wood waste loop closer

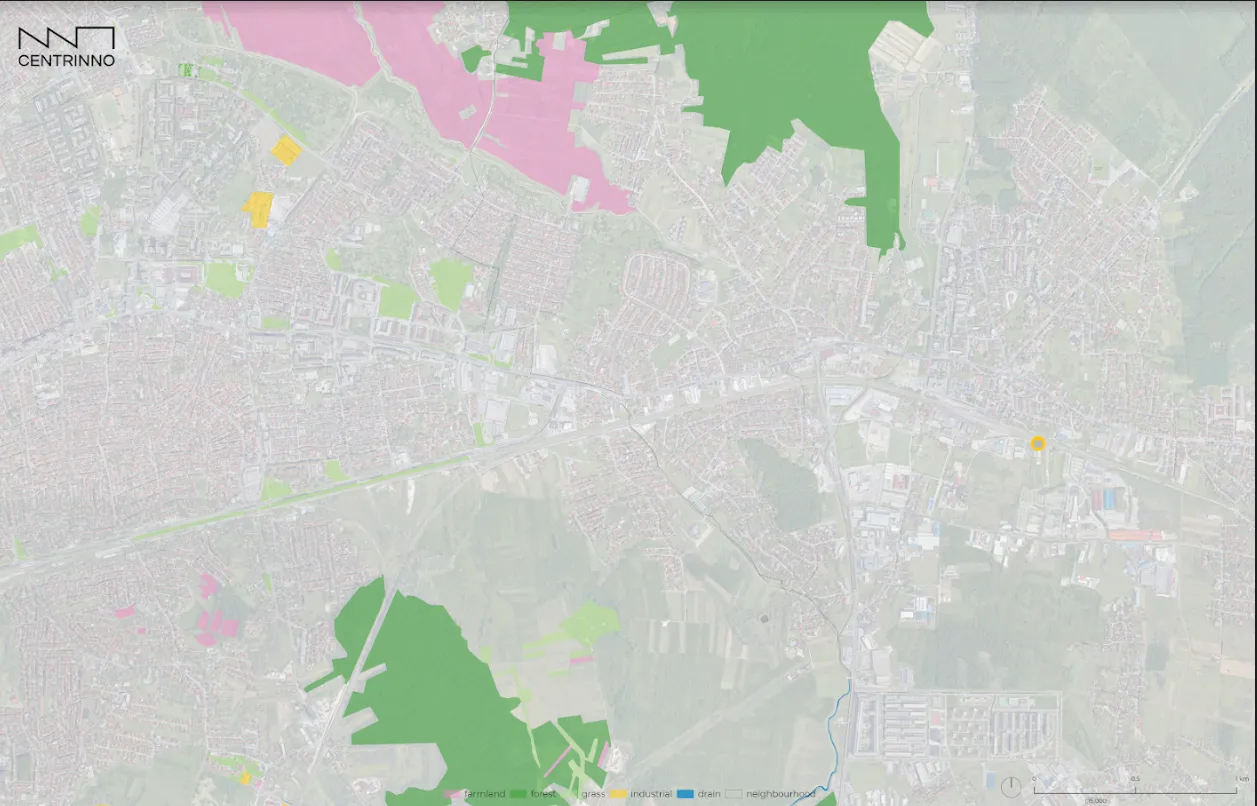

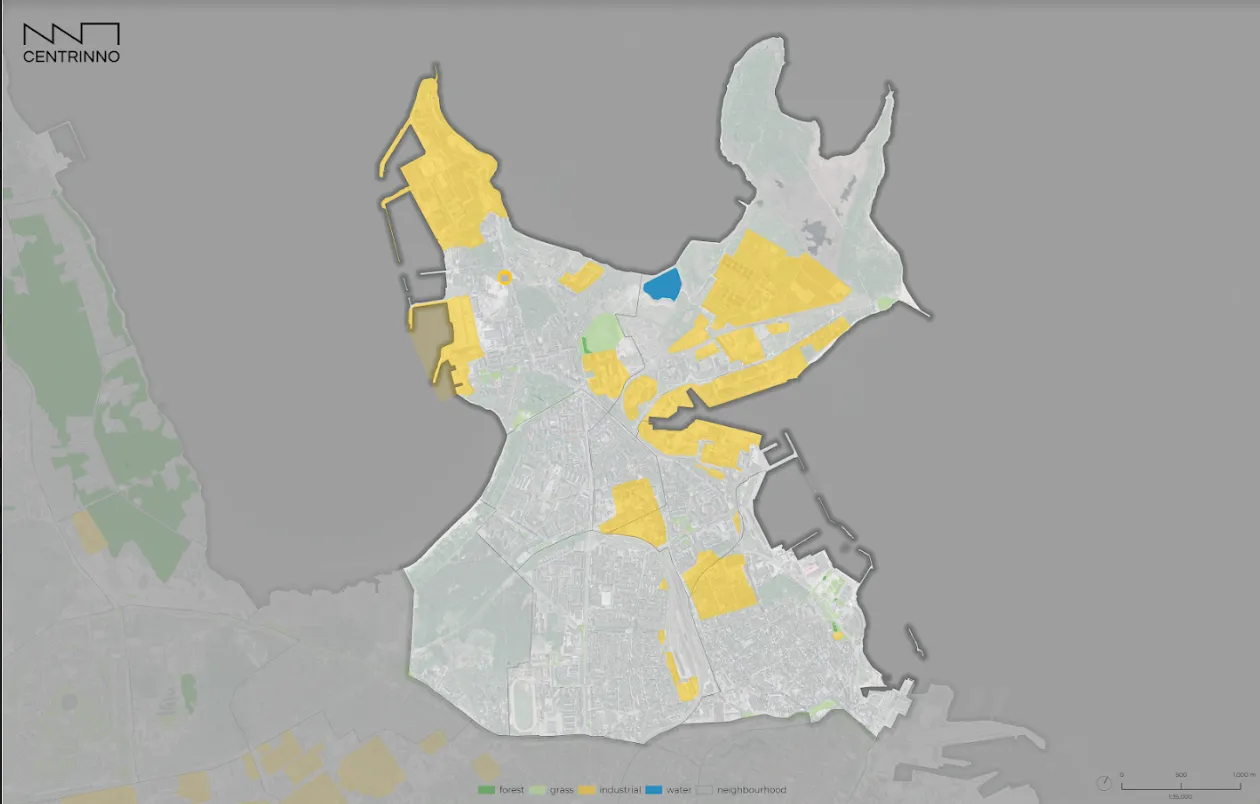

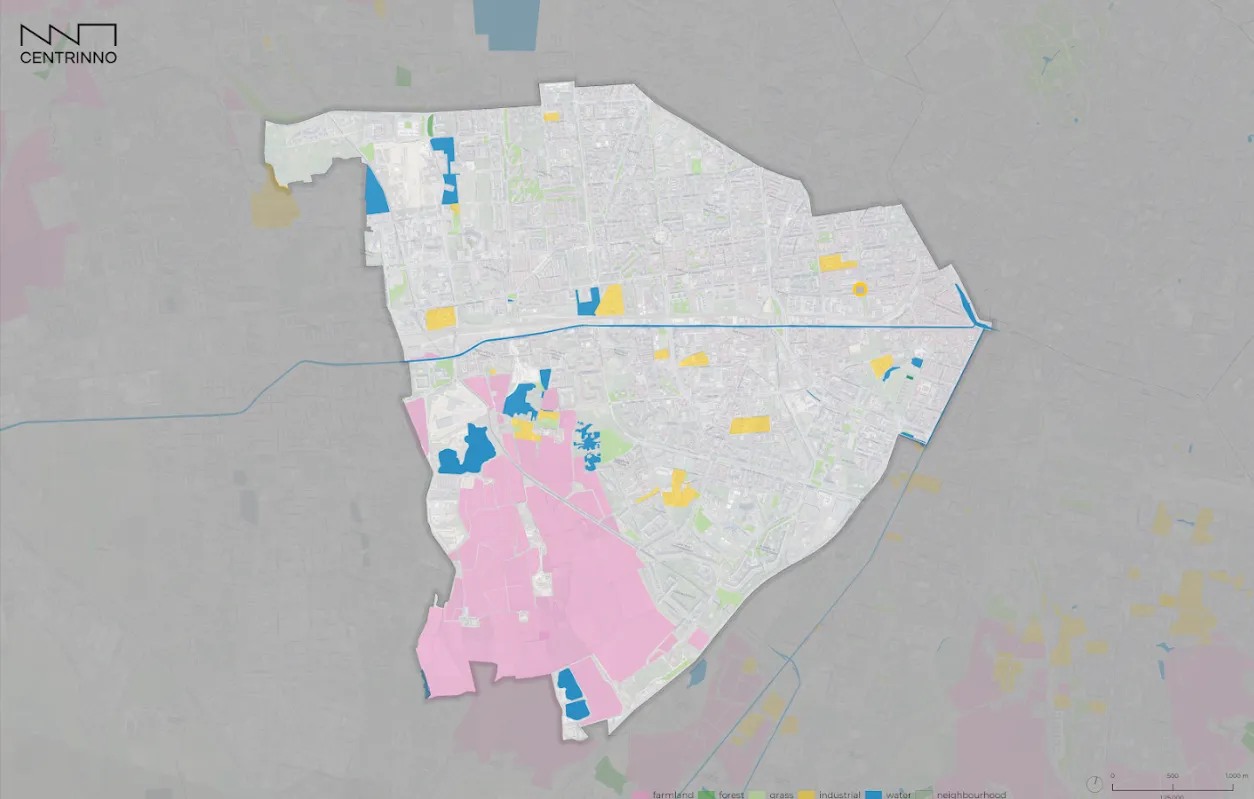

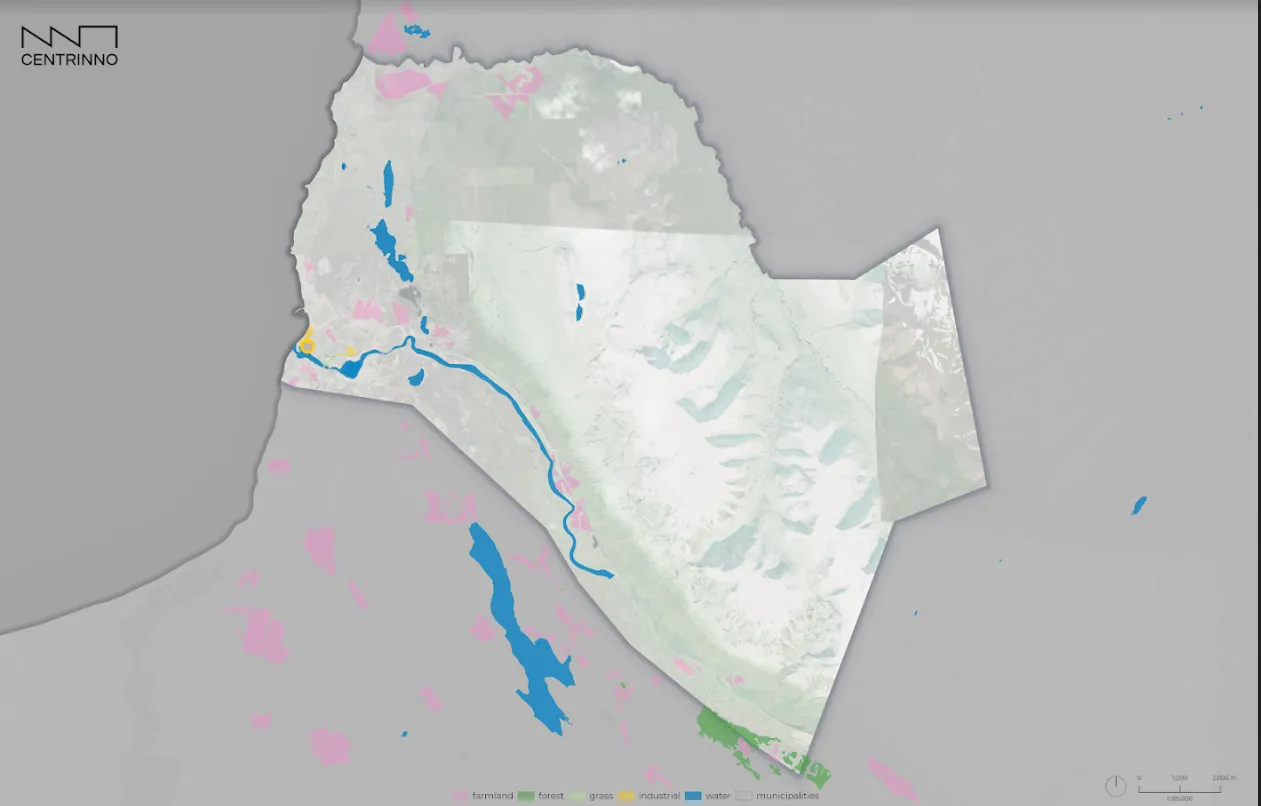

The ZIC is a hub of artisans amongst whom there are a number who use and work with wood in one way or another. For example, we find Les Deux Rivière, the city’s one and only mobile sawmill. Or Materiuum who work on recovering waste wood from construction sites right next door, traditional cabinet builders and kitchen builders. Wood waste from the ZIC is currently dropped off or collected by one of the city’s waste handlers, contributing to the 51,800 tons of city-wide wood waste collected across the territory from industrial and private businesses. The majority of this wood waste is currently incinerated, providing a significant resource for recovery. To get a better sense of which stakeholders are involved in the city-wide urban wood flows (and to identify better opportunities), our team started out with mapping the wood waste system.

Closing the loop on wood waste

We have mapped all wood waste collectors and other available information on the volume of wood waste in this interactive map.

Within Geneva, a large wasteflow comes from construction work, which produces significant amounts of wood waste. For example, in the greater city area, public works are estimated to require over twelve thousand tons of timber for building activities, meaning a potential waste flow might arise there.

Using wood waste for healthier soils

Like in many post-industrial areas, soil contamination is still a legacy of past manufacturing activities. An inventory of polluted sites in Geneva shows that the ZIC and a fair number of locations in the area are currently listed as “polluted” [1]. Luckily, the ZIC itself has been evaluated as not harmful, requiring no remediation activities. For many others, decontamination of soils has been done in the process of preparing sites for the construction of new buildings. However, soil quality and pollution around post-industrial sites remains a difficult topic. For one part, because it is challenging to identify where even mild soil pollution continues to exist underneath sealed surfaces and buildings. But also because soil decontamination and soil quality improvement often relies on the import of precious topsoils from outside the city. Yet, one thing is certain. Urban soils, whether heavily polluted from industry or highly modified by compaction or soil sealing are often highly compromised. Yet, healthy soils are paramount to provide soil ecosystem services, such as water retention, food production and carbon storage [2]. Getting a better understanding of the soils around us and finding opportunities to use local resources for increasing their health is paramount to create green and thriving cities.

Map 1. Potentially contaminated sites around the ZIC. Source: SITG Geoportal

How can wood waste and other locally abundant biowaste be used to regenerate the fertility and functions of urban soils?

Biochar – feeding the soils

Wood waste from ZIC’s woodworkers, urban tree maintenance and local construction waste could help us tackle some of these issues by providing feedstocks for the production of biochar – an interesting soil amendment for polluted soils. Biochar is generated through the heating of carbon-rich biomass – such as wood – without any addition of oxygen. Using local wood waste to produce biochar could be an interesting option due to its benefits as a carbon storage, its ability to immobilize contaminants in soils and improve the fertility of soils for food production [3].

As a cluster of woodworkers, artisans and an urban sawmill, the ZIC could become a testing ground for local biochar production and urban soil remediation. Saw dust from Geneva’s urban sawmill Les Deux Rivière together with left-over wood and clean sawdust from ZICs cabinet builders and carpenters could be locally processed in a small-scale biochar generator to produce soil amendments for the site itself and beyond. Also ZICs food waste and by-products from food industries, such waste sludge from the brewery Brasserie du Mat could be generated into biochar.

To start with, generated biochar could be added to Geneva’s first Microforest located on the ZIC. With Geneva aiming to improve its green cover and replicate the micro forest concept piloted at the ZIC, a healthy soil that can support healthy trees is more important than ever before [4]. Research has already shown that compost and biochar improve tree growth in urban soils [5].

Biochar is no silver bullet and there are a number of factors we need to consider. First of all, the quality of the ‘feedstock’, in this case wood waste, needs to fulfill specific requirements to generate high-quality soil amendments. Interviews with woodworkers in the ZIC highlighted that a lot of wood waste currently incinerated contains different additives, such as glues and paints. Research has found that treated wood can contain harmful heavy metals which are not suitable for food production or soil remediation [6]. However, the treated wood biochar could nonetheless be used in other applications like landscaping, of which the European Biochar Certificate (EBC) lists a few [7].

One opportunity to improve the quality of the wood waste would be to organize workshops on adhesives for wood which are compatible with a circular economy. The ZIC already has stakeholders, such as Materiuum, who are developing unique knowledge connected to circular processes within construction, including ecodesign and the reuse of materials. Materiuum is offering training and consultancy services which are getting increasing attention from the public and the private sector. But raising awareness and showing opportunities on bio-based glues, varnishes and paints is essential to enable a circular wood economy in which wood can be fully recycled, upcycled and composted. There are a number of practical examples of businesses innovating and selling such adhesives, such as the Switzerland-based Alfapura selling cradle-to-cradle certified wood glues.

A central question remains on which parties need to be involved to make such activities truly impactful. For example, if ZIC makers get their wood from larger, regional wood retailers, then the most significant impact should be made there. In this scenario, a workshop with both these retailers, ZIC makers and innovative parties like Materiuum, would be the best step forward.

Next steps

Biochar technologies could play an important role in tackling the dual challenge of urban soil regeneration and waste management of wood industries. The ZIC, as a cluster of many small-scale wood-related trades, could serve well as a potential testing ground to further explore this circular synergy.

That being said, work is only starting. As so often, our research brought up more questions than answers which the CENTRINNO team in Geneva will explore during the next spring. Above all, assessing the feasibility of a decentralized biochar generator heavily depends on the quantity and quality of feedstock. During the next months, we will investigate the possibility to set up a centralized wood waste collection system across the site that separates treated and untreated wood. With the knowledge of volume and consistency of wood waste streams we can then assess whether and which technological solutions make sense for our site. We will further continue mapping larger saw dust suppliers in the area to achieve a critical mass for testing our biochar solutions.

We will also dig deeper on other data, such as the site’s heat and electricity demands and local soil conditions to understand both the need for biochar and potential by-products from biochar production.

Last but not least, we have a long way to go to understand the governance model, legal requirements and financing model of biochar generation. Connecting with Swiss biochar experts on available decentralized technologies is key to get a clearer understanding of our options. For now, the outlook to close loops locally is exciting and we are looking forward to the work to come.

??Check out the article and the interactive maps on the cartography site!