BLOG

Towards edible cities

Towards edible cities

Towards edible cities

Cities have emerged and evolved in symbiosis with the nurturing spaces that surrounded them. The disconnection of cities from their rural environment is very recent (late 19th century). However, we are now witnessing a twofold process that aims to reintegrate agriculture into the heart of cities by updating certain market gardening practices and by creating new pacts with a peri-urban fabric torn between two worlds, the metropolitan space and the rural space.

By Sébastien Goelzer – co-fonder of Vergers urbains

The legacy of old Parisian market gardening practices

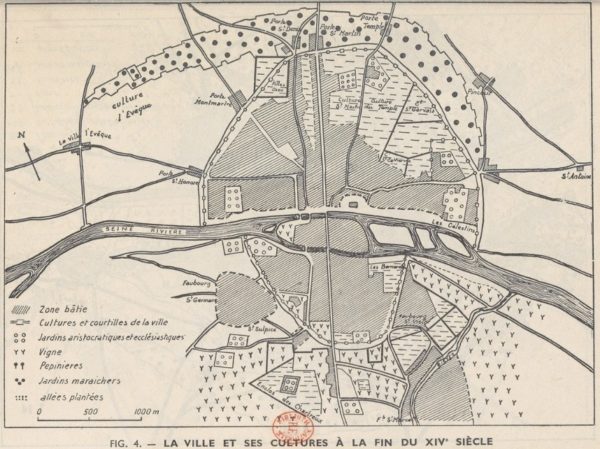

”Eating locally” is often seen as an injunction, but it is a means to an end, not an end in itself, which allows us to situate an action, to weave local networks, without forgetting the macro-economic issues that can respond to social injustices. Will urban agriculture feed the city, make us self-sufficient? This is the most frequently asked question, to which it is often retorted that this is not its objective. But we forget that in the not-so-distant past, cities drew most of their food resources from the surrounding areas. This is the case of Paris, which was one of the largest Western cities between the Middle Ages and the industrial revolution. The fertile Parisian basin provided a large part of the capital’s supply and exported its surplus to other cities. With 1800 hectares, 16% of the surface of Paris was occupied by market gardeners in 1830. In 1960, more than 20,000 hectares of vegetables were grown in the Ile-de-France region.

Yellow onions from Aubervilliers, asparagus from Argenteuil, sorrel from Belleville, cherries from Montmorency, strawberries from Bièvres, mushrooms from Paris… are all varieties that have been developed over the centuries on the Parisian soil. Peaches from Montreuil could thus be found in Saint Petersburg and asparagus from Argenteuil in London. The density of the Paris market led to the specialisation of agricultural activity in the Paris area in market gardening and encouraged the development of intensive techniques in terms of both labour and fertilisers. The inputs came from the reuse of city waste, brought back by the market gardeners when they returned from the Halles market. According to Jean-Michel Roy, Paris gives back in fertiliser what it receives in food. These techniques include espalier crops, greenhouse frames, forcing crops under cloches, hot beds, density, counter-planting and intermingling of crops, rotations, etc.

Map of Paris at the end of the 14th century. From La vie rurale de la banlieue parisienne : étude de géographie humaine / Michel Phlipponneau. 1956. Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Montreuil, fruit walls © Sébastien Goelzer

It was following the rural exodus and immigration in the 18th and 19th centuries that market gardening in Paris underwent rapid improvement, an unprecedented dynamic of agricultural innovation, thanks in large part to the mixing of cultures and practices, and the exchange of techniques between people from different provinces or countries. The royal gardens, especially the king’s kitchen garden, with the work of Jean-Baptiste La Quintinie, participated in the research and development of these techniques, which were then taken up by the gardener-gardeners of the capital. Conversely, the work of the latter had an influence on that of La Quintinie.

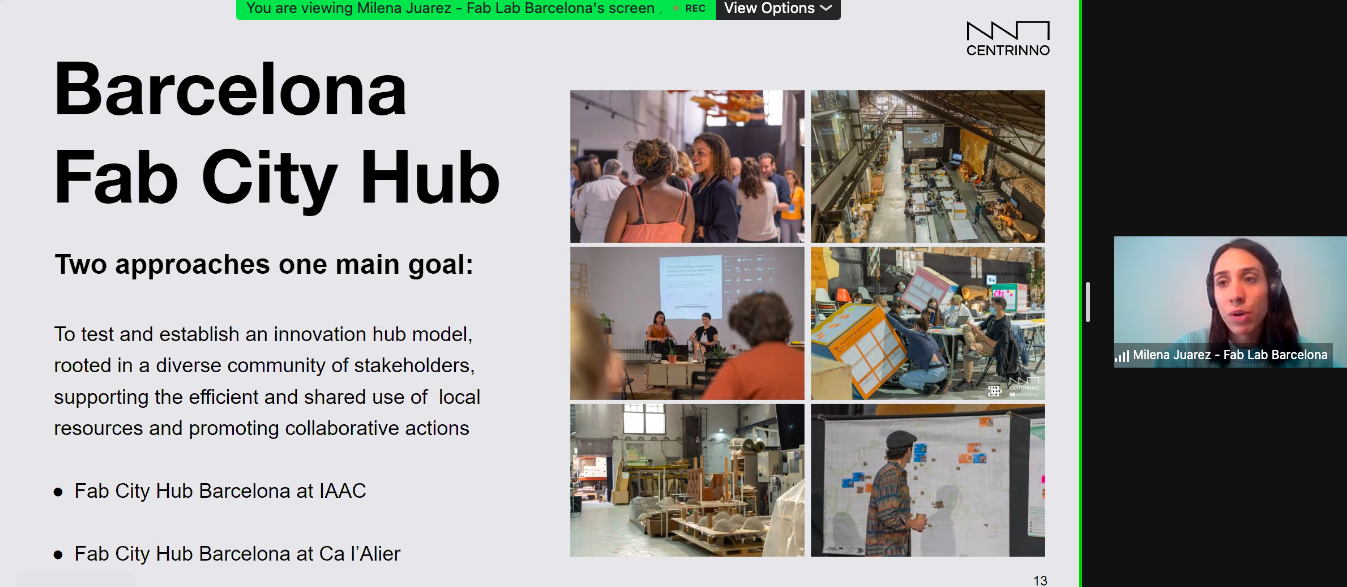

Contemporary urban agriculture makes it possible to rediscover this mix of experiences and innovations: it has become the heir to this tradition, which was lost for a few decades and is coming back through other doors. Pressed by social, economic, environmental and urban issues, we are barely rediscovering this economy that was created around the feeding of cities, by the city.

The techniques of the 18th and 19th centuries were described in the Manuel pratique de la culture maraîchère de Paris, by Moreau and Daverne1. Today, they inspire the pioneers of small-scale farming and permaculturists. Indeed, what is described in this manual is none other than the functioning of an urban micro-farm, which makes it possible to grow melons from April onwards, for example, or to produce up to eight vegetable harvests in a year, without chemicals, without mechanisation, without fossil energy, with locally selected seeds, contributing to the capital’s food self-sufficiency, at least in vegetables.

Ways to make cities self-sufficient

The rediscovery of this knowledge was undertaken in particular by Eliot Coleman, a Californian pioneer of organic farming in the United States, known as one of the instigators of the bio-intensive market gardening system with John Jeavons and Alan Chadwick. He met Louis Savier, one of the last heirs of these practices, in Paris in 1974 and thus followed in the footsteps of the London market gardeners who, before him, in the 19th century, went on study trips to Paris to find inspiration and refine their techniques. The Manual’s fame spread beyond the borders.

Eliot Coleman, author of Four Season Garden, evokes in his book, his Parisian trip by divulging his well inspired techniques. Jean-Martin Fortier, one of his disciples, was the author of The Market Gardener. This book, which is a reference for many new farmers, with No Agricultural Background (NAB), opens with a history of agriculture in Paris.

It is thus thanks to the North Americans that these forgotten Parisian techniques have been given a new light… in France, helped by well-known NABs: Perrine and Charles Hervé-Gruyer with the Bec-Hellouin Farm, largely inspired by Eliot Coleman and Jean-Martin Fortier.

Bec Hellouin Farm. Inspired by both agroforestry and intensive organic market gardening © Sébastien Goelzer

The development of these new practices on the North American continent and elsewhere also owes much to Alan Chadwick. Inspired by biodynamic agriculture, he helped spread the concept of Bio Intensive Farming or the “French method” with the aim of developing high yields with very little investment, using manual techniques that allow the same yields to be achieved as those of a mechanised market gardener, but on 1/10th of the area.

For some contemporary followers of this method, 1000 m2 is an area beyond which mechanisation becomes necessary and where the increase in labour is such that the size of the investments and operating costs cause the profitability of the farms to fall. In his book “Small-scale market gardening, the French Method”2 , Christian Carnavalet compares these traditional models with the practices of contemporary pioneers and shows that these yields can now be achieved more easily if modern tools are used at the right times and in the right places (irrigation systems, winter sails or the mechanical shovel for initial soil preparation). The challenge is not to copy the model but to update it according to our current knowledge and techniques. With only 1.5 Human Work Units, on 1000 m2, he shows through some examples that it is possible to generate between 20,000€ and 50,000€ in turnover. That is to say, as much as a mechanised market gardener on 1 hectare, with an investment 50 times less. This viability is reinforced if several French Méthode farmers join together in a cooperative, for example 9 or 10 farmers on 1 hectare, sharing certain tools, sales, purchases, logistics, etc.

Christian Carnavalet refers, for example, to the figures of Pierre Kropotkine3 who, during a visit to France, visited the Parisian marshes, including that of Isidore Ponce4 and gave a precise description: An annual production of 172 tons of vegetables on 1.1 hectares by 8 people (whose value would be equivalent to 472,700€ at retail today). This is far from mechanised vegetable farms but close to the profitability of contemporary intensive organic micro-farms (Neversink Farm in Claryville in the United States, Ferme du Bec Hellouin in France, Green City Acres in British Columbia, or Martin Fortier’s Jardin de la Grelinette in Quebec…). The feeding capacity per unit area is thus well above the figures proposed by Parcel5, an application developed by Terre de liens based on INRAe6 figures. In Ile-de-France, to feed 12 million inhabitants… some 3.6 million hectares would be needed using conventional methods, i.e. no less than six times the current useful agricultural area in Ile-de-France (569,000 ha in 2018, source: Agreste), with a sharp reduction in animal products (-50%). These techniques are currently being promoted by the FAO (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation) as a means of helping certain developing countries achieve a certain degree of food autonomy, through a training programme supervised by John Jeavons (one of the main advocates of these traditional methods), under the name Grow Bio Intensive Farming (BIF).

There are very few examples in France, with the Bec Hellouin farm already mentioned as a pioneer. Several micro-farms have been studied from the point of view of viability by Kevin Morel7 , but they are generally on larger surfaces or do not derive all their income from their production. The challenge now is to demonstrate the viability of these 1000 m2 farms more widely and to open up fields of experimentation with the installation of market gardeners, accompanied and trained in these techniques. The main obstacle is currently the lack of training courses likely to disseminate these techniques and above all the preconceived ideas against any system wishing to demonstrate its viability on less than several hectares.

Urban agriculture revisits old practices

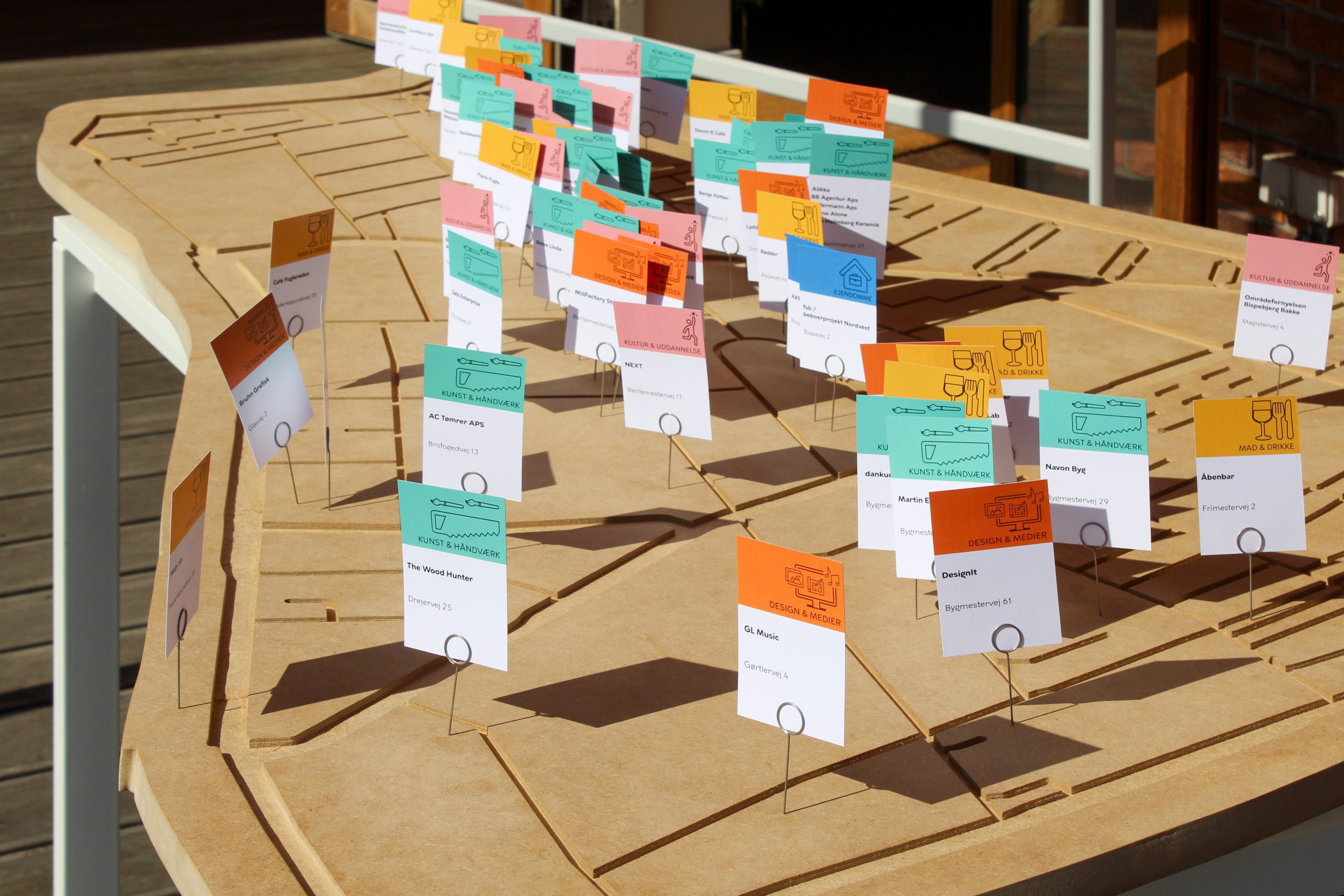

In 2019, the exhibition Capital Agricole at the Pavillon de l’Arsenal8 highlighted both this heritage and the urban farmers who are taking up the torch of this innovative dynamic.

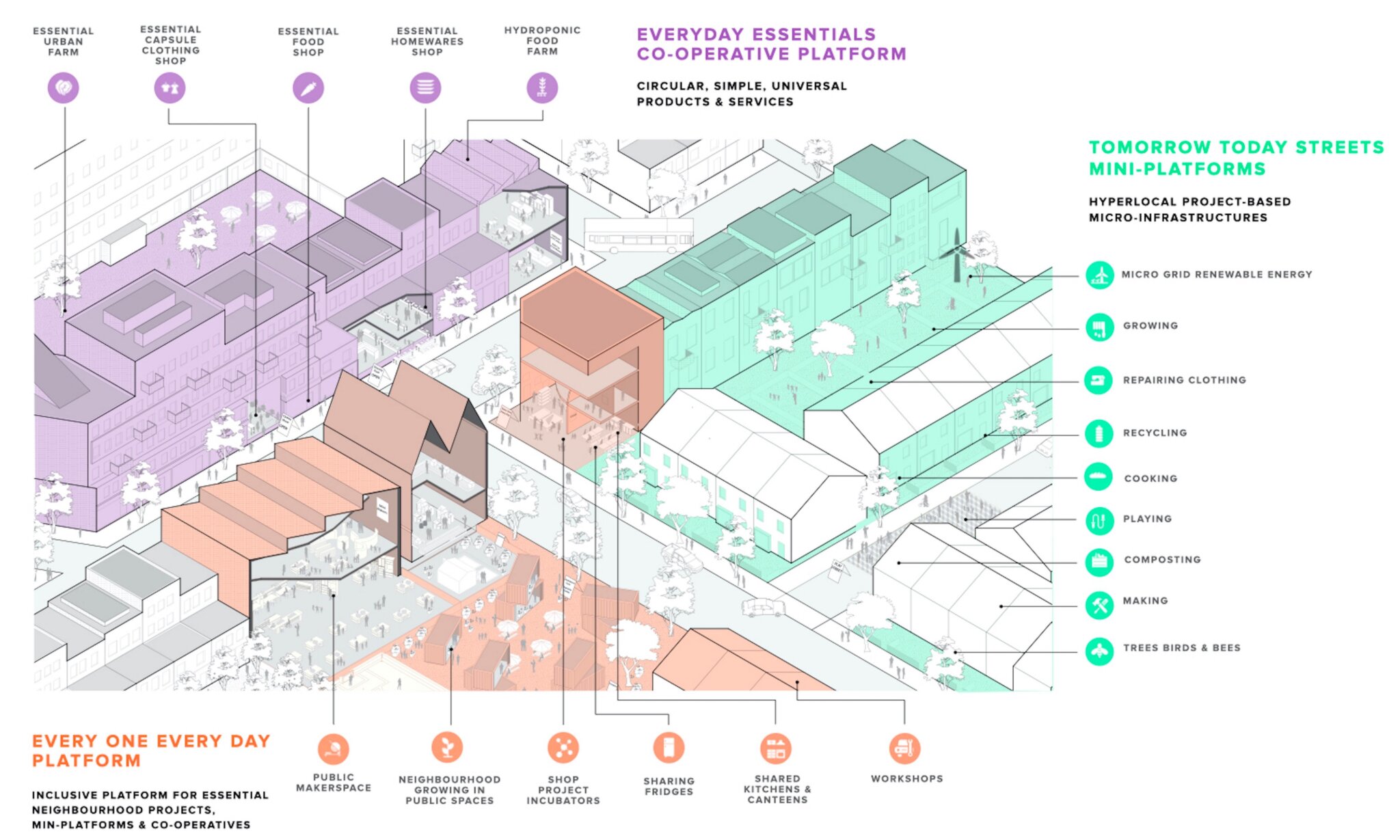

In the 175 years since the textbook was written, growing techniques have greatly diversified (more or less high-tech, with hydroponics, aeroponics, or mushroom growing in car parks, vertical roof gardens, micro-foam crops, etc.). ), new ways of processing in the city have appeared (shared kitchens, or other foodlabs), of distributing (neighbourhood food halls, food baskets, farmers’ markets, etc.), of recycling city waste (recovery of spent grain, mushroom growing substrates, coffee grounds and soon human urine again, etc.), or simply the revival of forced cultivation under a frame or under a bell (for example by recovering used beer kegs, keykeg type).

Like the former market gardeners (often referred to as “specialists”), urban farmers have specialised in the most fragile products that are difficult to transport over long distances (leafy vegetables, herbs, fruit, melons, mushrooms, cut flowers, etc.) and have a high added value.

Toit du Bout du Monde. Centre Jean Dame, Paris 2e, géré par Toits Vivants. © Sébastien Goelzer

Toit du Bout du Monde. Use of warm layers, mulching and amendments based on compost, spent grain, cocoa pods, champost, crops under cloches (used keykeg)… © Sébastien Goelzer

Urban farmers are just as subject to the development of urbanisation as their predecessors, but they are seeking to return to the heart of the city to take over its interstices, its temporary wastelands or its car parks and rooftops, the rare urban spaces that are conceded to them. Their role, for lack of a suitable surface to really feed Parisians, has diversified to meet social and educational challenges, which does not make them any less essential players in the urban space. The development of urban agriculture is based on the observation that agricultural production has gradually moved away from urban centres, and many of the rings identified by Von Thunen7 have disintegrated.

It is not the increase in the number of urban mouths to feed that has broken the capacity of cities to be largely self-sufficient, but a change in the economic model, where agricultural production has become largely dependent on oil, the food industry and large-scale distribution. Agricultural areas have become physically and mentally disconnected from the heart of the cities, and a disappearance of know-how has finally completed the interaction between town and country. The rediscovery of small-scale cultivation techniques has opened up new avenues for reestablishing links and reanimating certain areas.

Towards a reconciliation between town and country

Today, there is a craze for the development of market gardening “belts”, linked to the rural world, at the interface of a double movement: ruralisation of towns and urbanisation of the countryside. A movement that responds to a craze for the local and a dynamic of proximity, but which often forgets that the crops that take up the most space are those that make up the major part of the population’s diet: field crops, mainly cereals (depending on the food crops and the climate, these can be wheat, barley, rice, maize, etc.). Crops subject to international markets, far from cities despite their spatial proximity.

A new solidarity between the city and its hinterland must be (re)constructed, by returning to the virtuous forms that have shaped our territories, with the integration of new, more diversified and resilient modes of cultivation. Our rural and peri-urban territories can turn to agroforestry, give a greater place to mixed farming and livestock breeding, allowing fertility transfers maintained by outdoor livestock breeding, by associating legumes among the crop cycles to reduce the need for nitrogen fertiliser.

Ferme du Bonheur, Nanterre. 2012 © Sébastien Goelzer

With renewed diversity and smaller-scale cultivation, an image tarnished by the conventional model embodied by large-scale cereal crops can be restored. For urban dwellers, the image of the peri-urban agricultural area is greatly devalued, it becomes a sort of non-place, far from the image of an idealised, green and picturesque countryside. Hedges and copses have disappeared, rural roads have been closed or eliminated. In short, the landscape has become monotonous and frustrates the dreams of the neo-suburbanites of the countryside.

Not all agriculture is equally conducive to this close relationship. Some farmers, such as small-scale market gardeners, are better adapted to the urban or peri-urban context, they need access to the urban market and some urban dwellers seek access to fresh food at low cost, as well as the proximity of an authentic landscape. This is what food belts are all about, and their purpose is to feed, not just to develop a picturesque setting worthy of a Renaissance-style painting.

Gonesse, large wheat fields. Photo taken during an exploratory walk in 2016 organised for the summer workshops on urban agriculture and biodiversity. © Sébastien Goelzer

The question of soil pollution will arise. In any case, the success of micro-farms in intensive organic market gardening is essentially based on “constructed soil”, i.e. prepared and enriched with organic matter (manure, compost, green waste), disconnected from the existing soil. Moreover, as urbanisation pushed them further away, Parisian market gardeners used to move with their land, which they had spent years building up.

More and more local authorities are seeking to encourage the development of cooperatives, while preserving the agricultural vocation of the land. Some, aware of this potential, have launched calls for projects to exploit plots of less than 5,000 m2 , but underestimate the support required (on outlets for example), or the inclusion in a cooperative environment (in a network with other farmers for example, or in synergy with other elements of the context). A dynamic that can create self-employment and give access to land to people in precarious situations, so that they can earn a supplementary income.

Other towns are taking control of their agricultural production by creating an agricultural board, such as Mouans le Sartoux, which supplies the canteens of three schools with 100% organic food at no extra cost to the beneficiaries. The idea of creating an agency was born of the difficulty for the commune to ensure its supply from local farmers. Four hectares, then six, were acquired and converted to organic farming to supply the canteen with fruit and vegetables. The commune managed to lower the price of meals, despite the higher cost of vegetables compared to the market price, thanks to a policy of reducing food waste, which concerned almost 30% of meals.

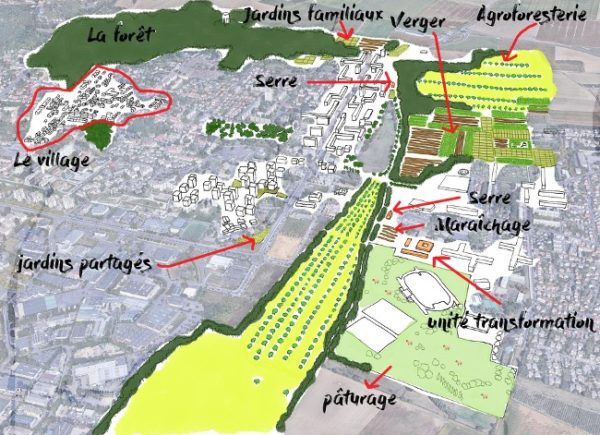

Towards the creation of agri-urban parks

These dynamics give farmers the opportunity to change their strategies: to adopt short supply chains, to turn to on-farm picking, to modify their distribution methods, to develop new activities with higher added value, more adapted to this proximity and with new relationships with the community. Farmers can become partners and not simply operators, or service providers, managers of the landscape. This implies a profound change in their profession, adding other strings to their bow and becoming aware of the expectations placed on them and the essential role they can play in their territory. Urban and peri-urban agriculture with a productive vocation can thus be fully integrated into the urban fabric and not be considered as a blank space on planning documents, or a land reserve, but as structuring spaces. The challenge is to give them colour and to consider them as full spaces, in complementarity with other forms such as allotments, shared gardens, or large-scale farming areas, participating in the reorganisation of cities. These spaces can take the form of large semi-public parks, within which productive, educational or commercial spaces have been set up on a local scale. They combine pleasure and production and integrate economic, environmental, social and cultural issues….

Agri-urban park project, Villiers-Le-Bel © Vergers urbains

According to John Dixon Hunt (The Art of the Garden & Its History) “in all societies, many of the formal elements of garden art have been developed from the agricultural landscape […] and that the third nature has merely taken up and refined already existing agrarian models”. It is conceivable that within this third nature the art of a garden cultivated in a concrete way, not only in its symbolism, develops and that these three entities hybridise, at least on their margins.

the Author : Sébastien Goelzer is a freelance urban planner, specialised in urban permaculture, co-founder of the association Vergers Urbains and the Collectif Babylone. He is involved in many urban agriculture and collaborative urbanism projects.

Source : https://www.revue-openfield.net/2022/02/01/villes-nourricieres/

NOTE / BIBLIOGRAPHY :

- Manuel pratique de la culture maraîchère de Paris / par J. G. Moreau et J. J. Daverne,… 1845

- Le Maraîchage sur petite surface – La french method, Christian Carnavalet, Oct 2020. éd de Terran

- géographe, anthropologue, activiste russe, théoricien du communisme libertaire, auteur de l’Entraide, ou La Conquête du Pain.

- Maraicher, auteur de la Culture maraîchère pratique des environs de Paris. (1869, la Maison Rustique)

- https://parcel-app.org

- https://www.inrae.fr/

- https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01930607v5

- https://www.pavillon-arsenal.com/fr/expositions/10992-capital-agricole.html#:~:text=La manifestation « Capital agricole – Chantiers,la ville et le sol.

- Economiste Allemand ayant décrit la manière dont sont organisés les espaces agricoles en fonction de leur éloignement par rapport au centre urbain

Le Maraîchage sur petite surface – La French Method. Christian Carnavalet, Oct 2020. éd de TerranManuel pratique de la culture maraîchère de Paris / par J. G. Moreau et J. J. Daverne,… 1845

La vie rurale de la banlieue parisienne : étude de géographie humaine. Michel Phlipponneau. 1956. Accessible sur gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Des légumes en hiver : Produire en abondance, même sous la neige. Eliot Coleman, Nov. 2013. Acte Sud.

Le jardinier-maraîcher — Manuel d’agriculture biologique sur petite surface. Jean-Martin Fortier. éd. Ecocité, Janv. 2016.

Capital Agricole, Augustin Rosensteihl Pavillon de l’Arsenal, Fév. 2019

Ville affamée Comment l’alimentation façonne nos vies. Carolyn Steel Rue De L’échiquier– juin 2016Sitopia, Carolyn Steel, Rue de l’échiquier. Sept. 2021

Jardinages en région parisienne. Jean-René Trochet, Jacques Péru et Jean-Michel Roy, Paris, 2003

Laure de Biasi, Jean-Michel Roy, La grande histoire des légumes et de leurs terroirs en Île-de-France. Note Rapide, IAU n° 868. Oct. 2020. Institutparisregion.fr