BLOG

Reclaiming locality: A path towards a brighter future for Sesvete

(Harry Reddick, part of the CENTRINNO partner Amsterdam University of the Arts, went to Zagreb on 04-02-23 to 07-02-23, to meet the Zagreb pilot team and their partners in the local area, and find out more about Sesvete itself. Below is his report)

The need for context

The challenges facing each site in the CENTRINNO project are rarely uniform. I wanted to know: when trying to initiate a sustainable transition, what is actually effective? How can these transitions succeed, when no one single blueprint exists towards implementing the vital changes societies need to move towards climate-minded cities? Each pilot site has its own history, its own context, its own tensions, populations, infrastructures, political battlegrounds, ecological/environmental situations, social debates, fragmented and contested identity categories… I could go on. In a site visit I recently undertook to Zagreb, and its pilot site in Sesvete (just outside of the Zagreb city centre), I began to understand just how important this context is for the work of CENTRINNO in the Croatian capital.

The former Sljeme meat factory

Image credit: Harry Reddick

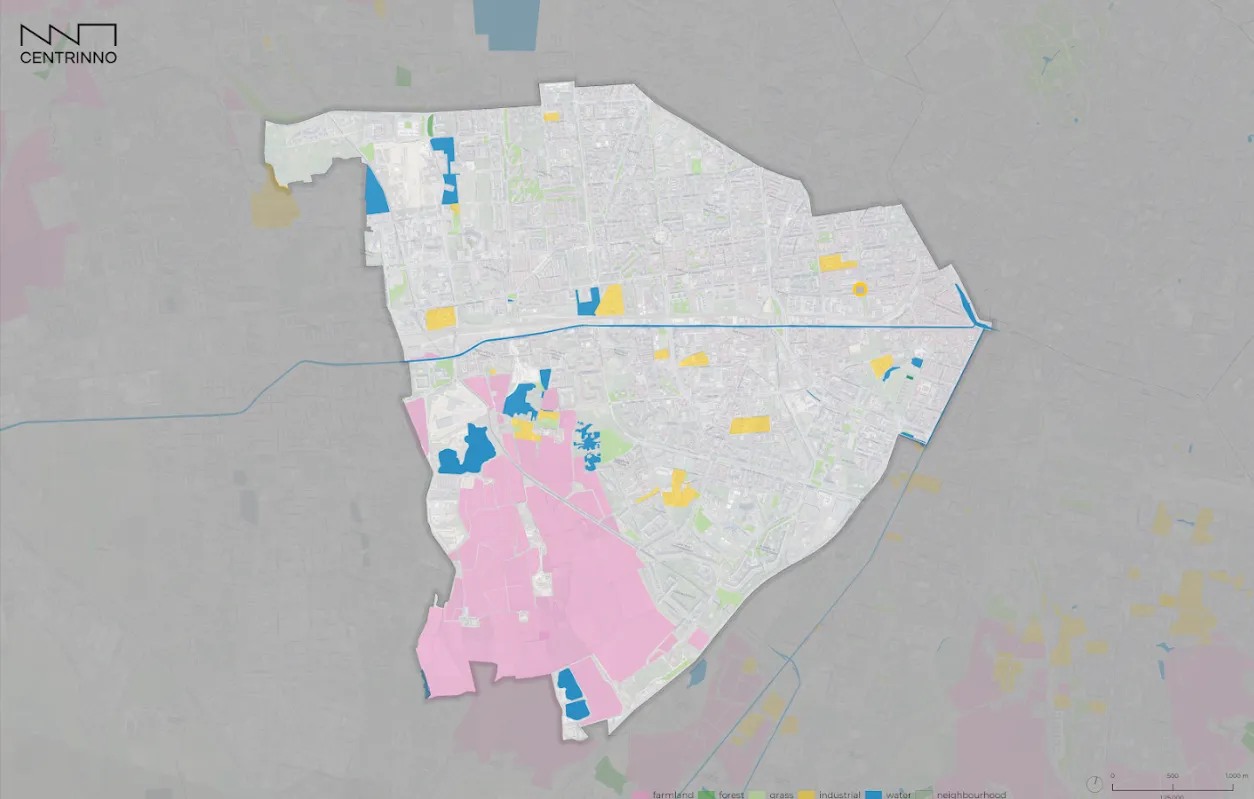

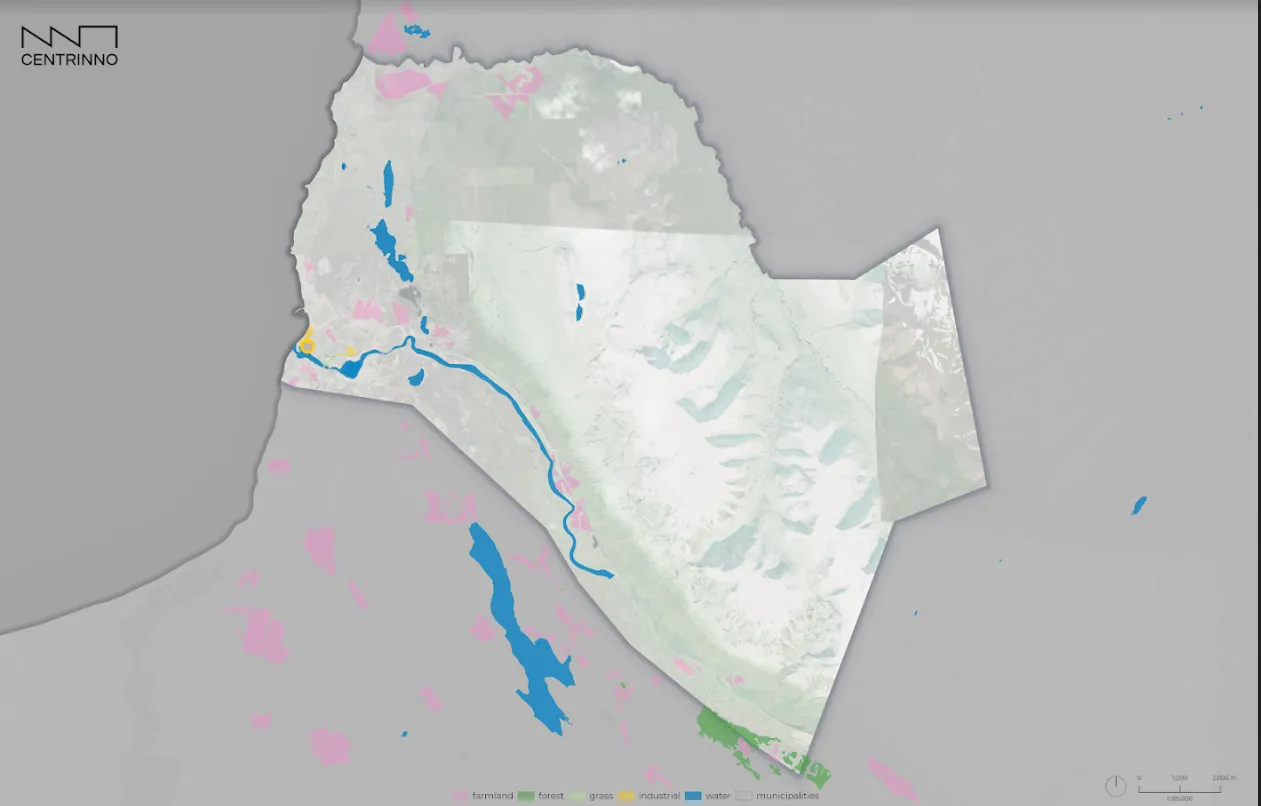

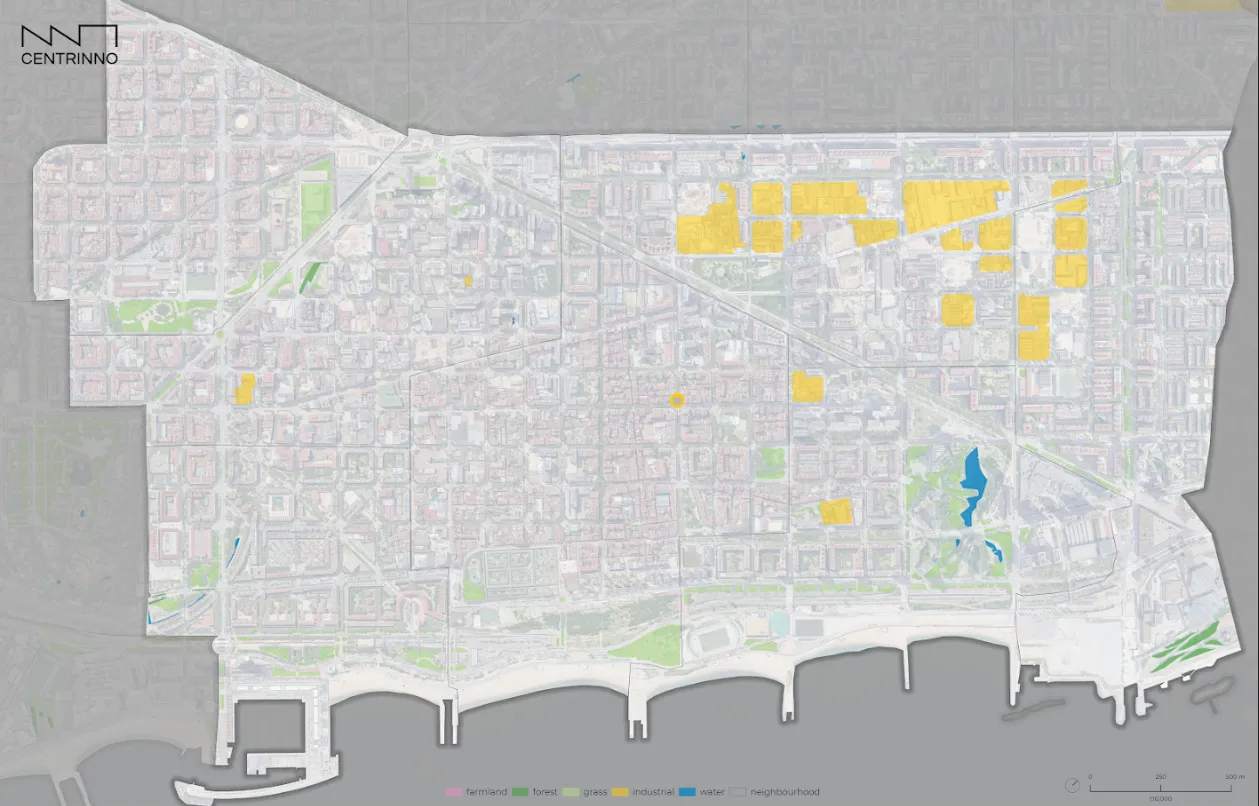

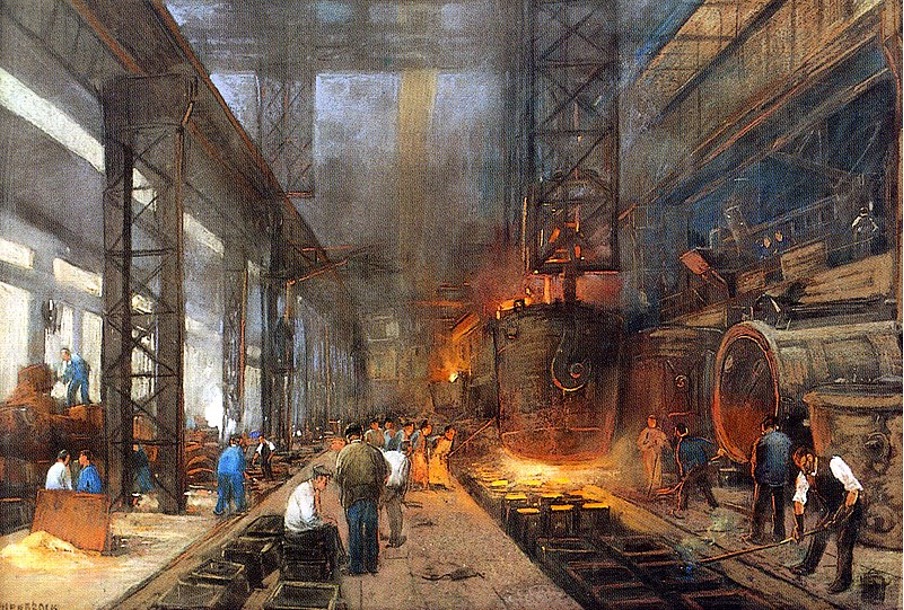

First, some background. Sesvete is the easternmost city district of the greater Zagreb area, with a population of around 90,000 people [1], which has three primary demographics: the traditional rural residents; the immigrant population who moved for industrial work; the refugees from Bosnia-Herzegovina and those affected in the surrounding areas during the war in the 1990s [2]. This makes it the largest district by population in Zagreb, and – notably – also the youngest. Located about half an hour by car from the centre, Sesvete is a district that feels like a town unto itself: indeed its status as part of the municipal voting jurisdiction of Zagreb is a relatively recent development (but one with some significance given the share – the largest – Sesvete has within the capital’s electorate). Sesvete is home to the former meat factory of Sljeme (closing in 2005), which had a footprint of some 285 hectares, and was the biggest meat-producing body in the world, with much of the space (about 185 hectares) now part of the city’s ‘masterplan’ for future urban regeneration, for a housing settlement for around 10,000 people. The remaining hectares are caught in an administratively-tricky ‘industrial zone’. As one would expect from such a large-scale employer and source of work, the area’s industrial trajectory has had a significant role to play in the intertwined social and historical lineage of not just Sesvete, but Zagreb as a whole.

Losing and locating the heart of Sesvete

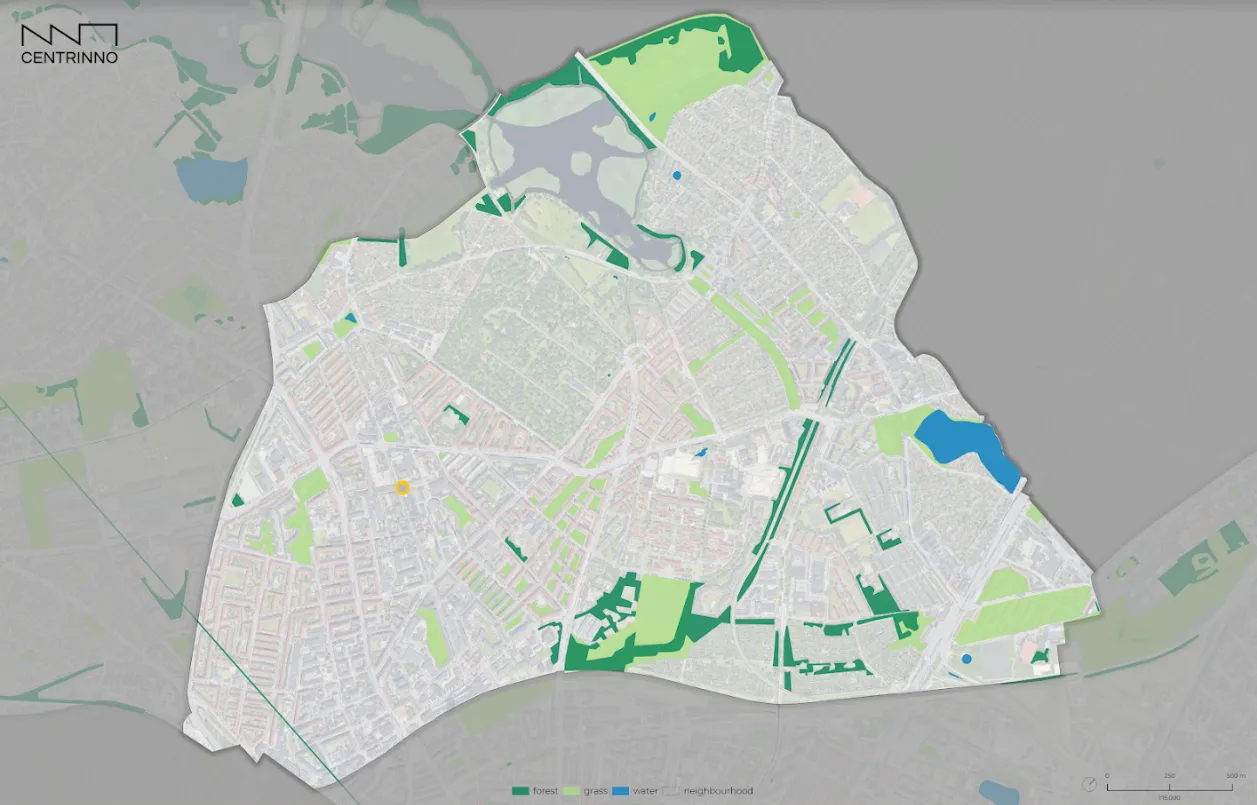

A local photography exhibition in 2021 was held to demonstrate Sesvete’s identity and distinct character. Of over 150 entries to the competition, not a single image was of Sesvete’s built environment, with every individual entrant instead deciding to submit photos of the natural landscape beyond the district’s urban boundaries. Put another way, no entrants felt that an image of the urban space of Sesvete could visually represent what they loved about the place they call home. What might that tell us about the way in which people relate to Sesvete as a place? Calling a place home suggests some kind of recognisable features that are relatable to the inhabitants, that allow them to furnish a place with meaning. There is, however, no coherent city plan for Sesvete, despite its historical significance and sizable number of residents. The district consists of small housing developments distributed unevenly along the train tracks, rather than coalescing into something resembling a city centre from which the urban space grows outwards. This lack of a ‘true’ city centre affects coherence of the urban experience when sensorially exploring the Sesvete area. As described to me by Bojan Baletic, one of the members of the Zagreb pilot team within CENTRINNO, the generation of a sense of belonging and even a cogent sense of place is hindered by this architectural dispersal of the urban landscape across parallel railway-adjacent settlements. If this lack of identification with the local has an architectural cause, is there therefore an architectural solution?

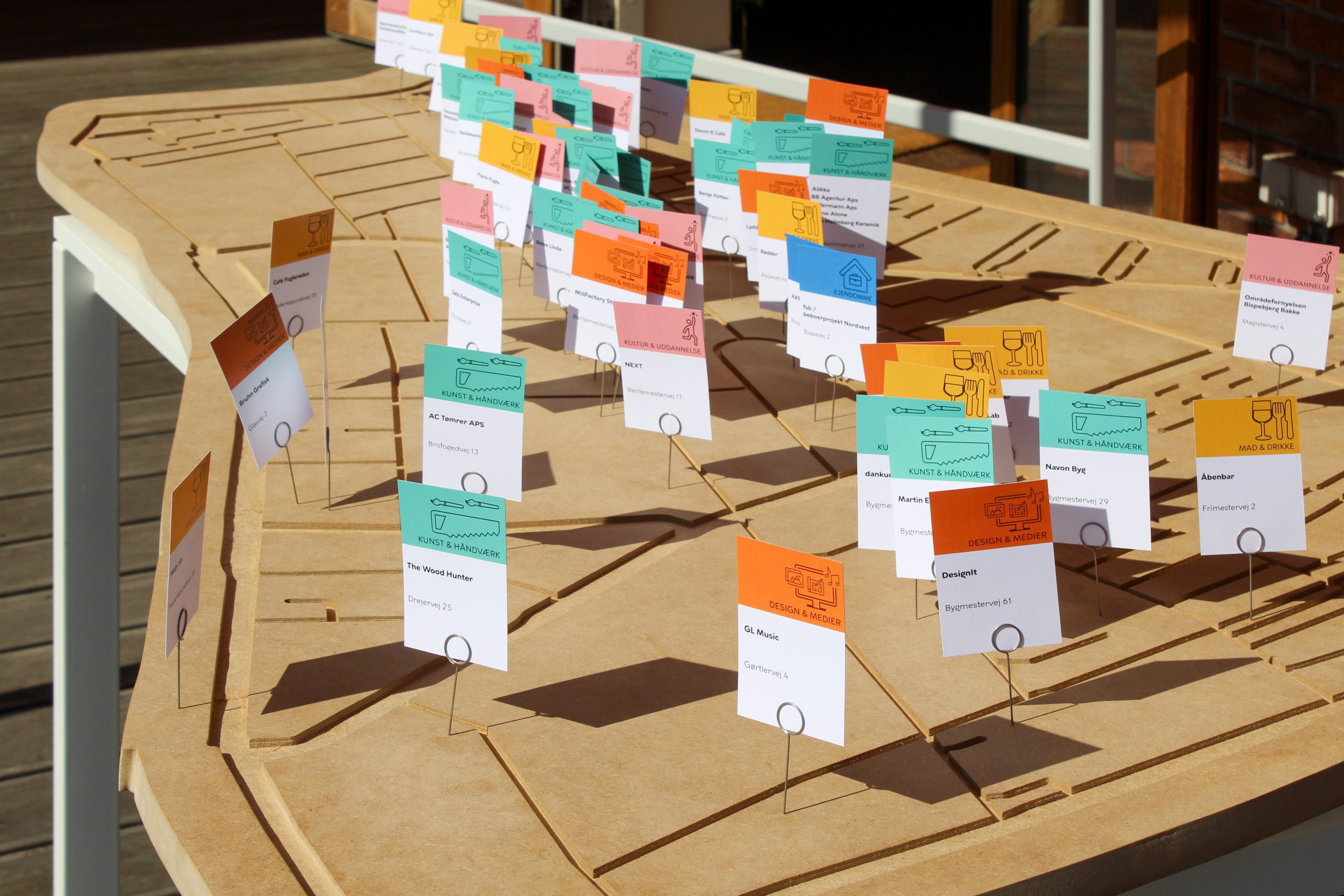

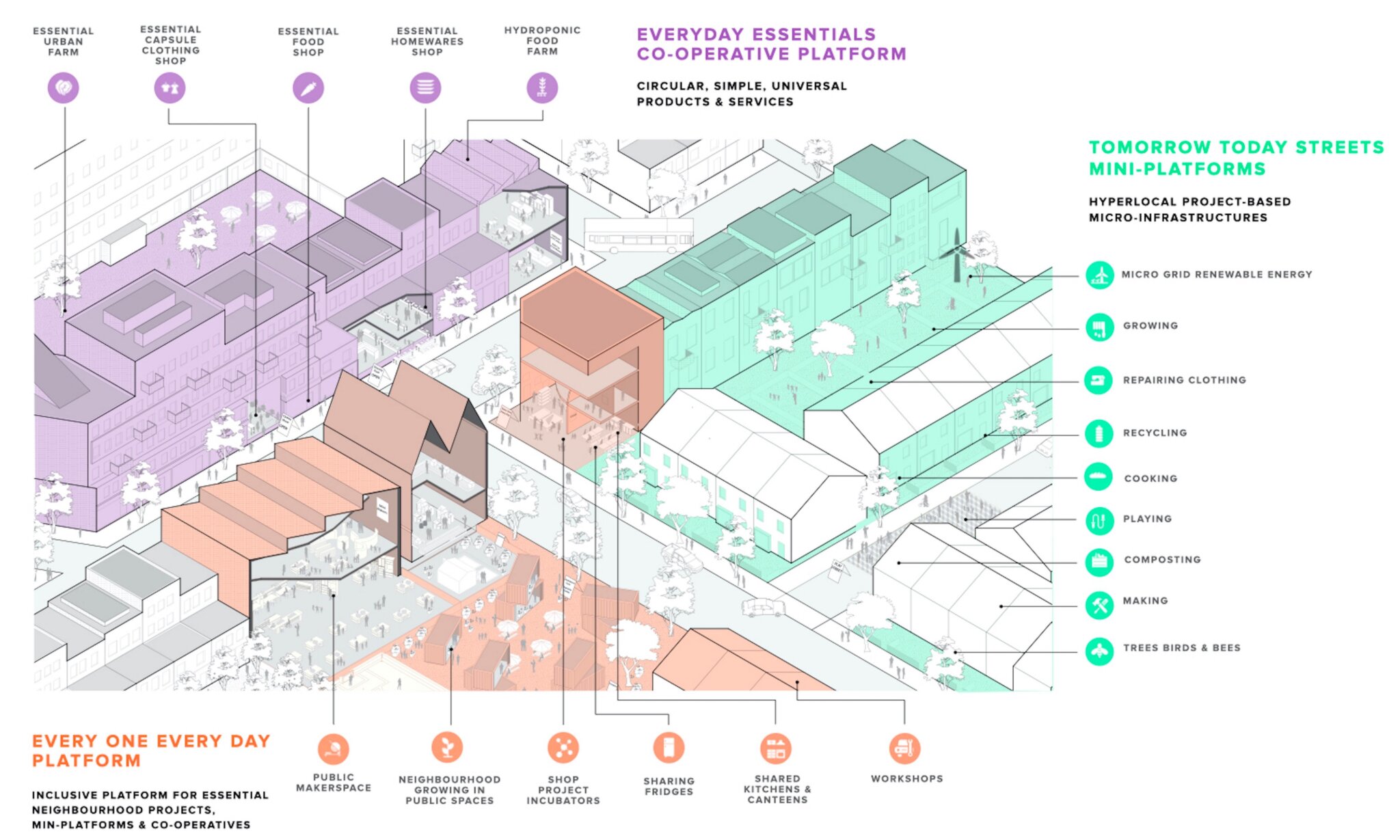

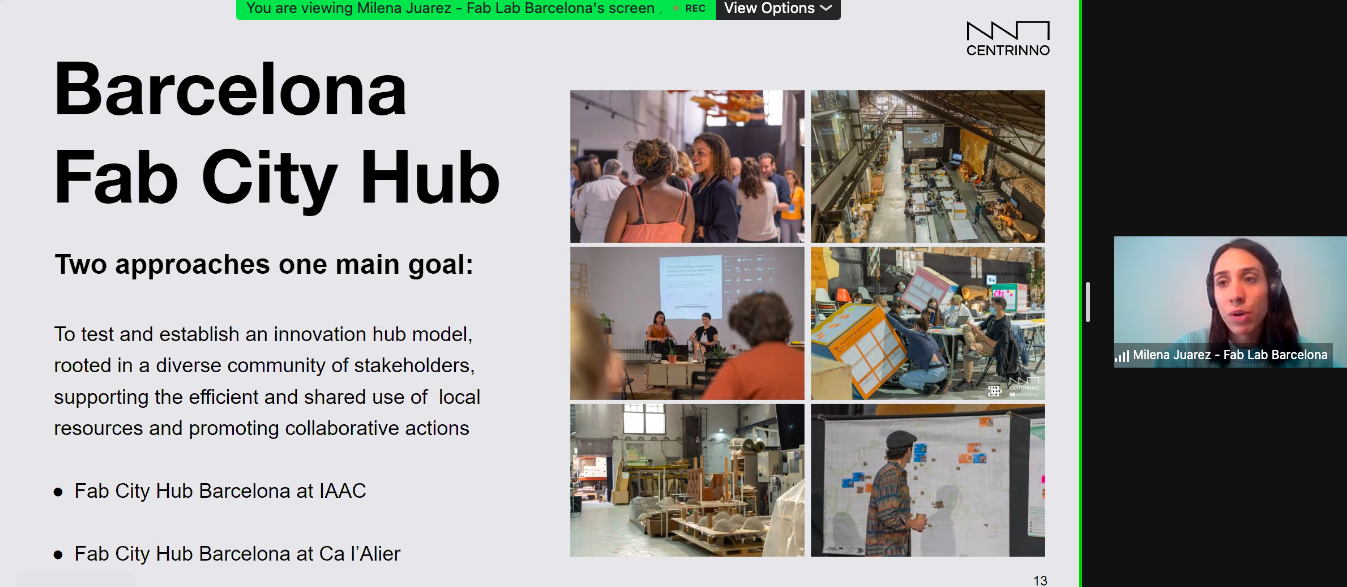

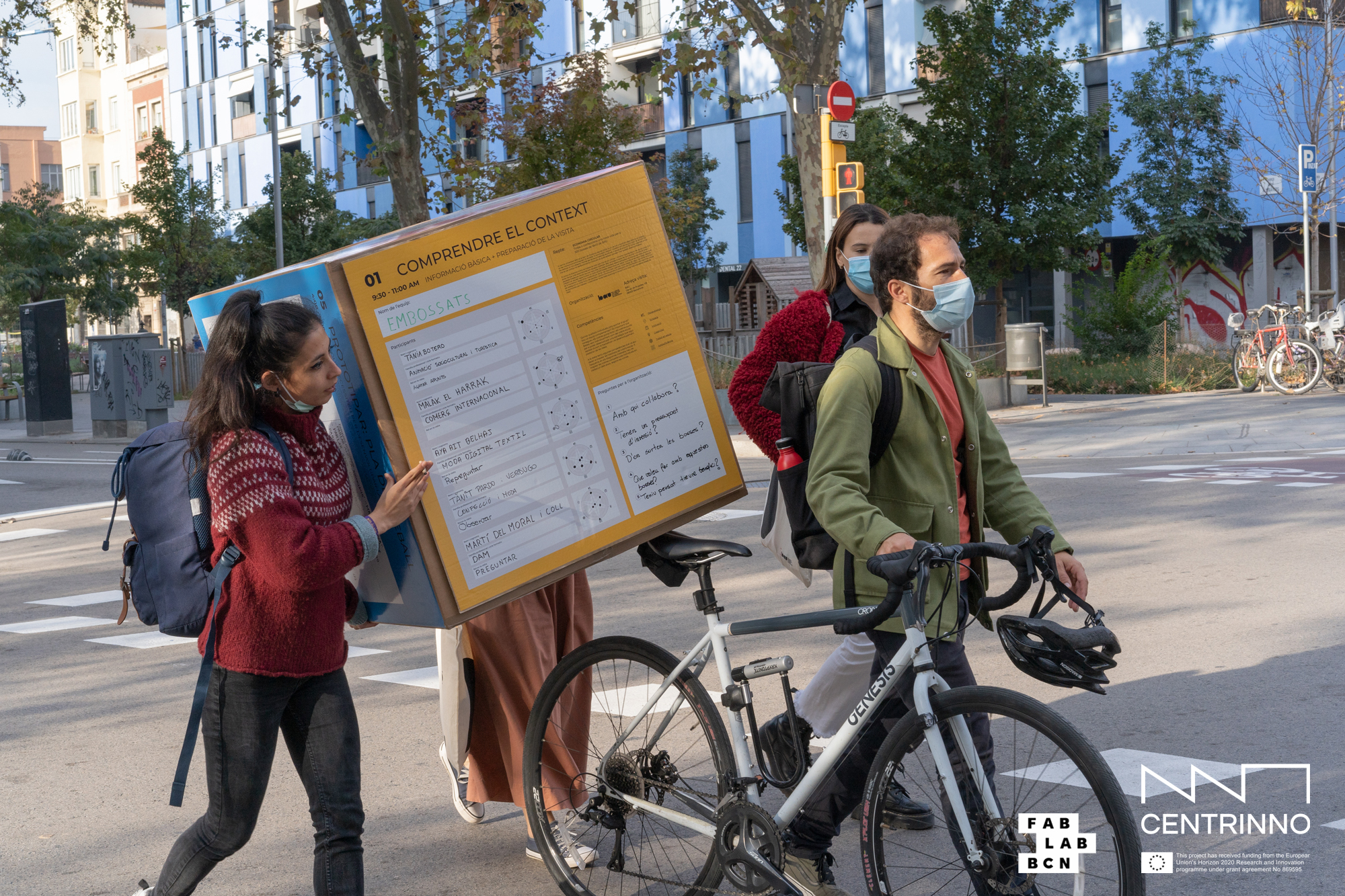

CENTRINNO’s representatives in Zagreb’s pilot team think so. Working in coordination with Fab Lab Zagreb in 2016, the group of architects and planners that would later become the CENTRINNO pilot team developed a new architectural scheme for the Sesvete area, having conducted extensive interview processes with locals to find out what they hoped for Sesvete in an uncertain future. The plans aim to bypass the sense of separation created by the train tracks, by connecting the old industrial space – with its new housing development – to the central area of Sesvete via a connecting bridge over the railway. In addition to this, the new development plans to build or renovate buildings for new manufacturing spaces via the creation of another Fab Lab (to replace the industries that collapsed in the 1990s and early 2000s), a new building for the Sesvete School of Music, which has an abundance of young talent but nowhere to practise, and much-needed revamps of the health, community, and security services. This is in addition to the already-implemented reuse of the old factory silos as the backdrop of a community garden, and the moving of the industrial zone to the western outskirts of the city.

The former silos turned into Community Gardens

Image credit: Harry Reddick

Green and Blue Sesvete: a community-led path to a brighter future

Such a plan aims to make this proposed new heart of Sesvete the fulcrum of the ‘green corridor connecting the ‘Green’ Medvednica, through the Sesvetska dolina, along the Vuger stream [through to] the ‘Blue’’ river Sava located beyond Sesvete’s southernmost boundary [3]. This architectural intervention thus inspired the name of the project (followed by an NGO of the same name): Green & Blue Sesvete. This formed part of the coalition working on the proGIreg Project, launched in 2018, also via Horizon 2020. Many of these local organisers, who previously found collective identification via the phrase ‘Sesvete in my Heart’, have been working together for many years. Green & Blue Sesvete’s members certainly carry with them the heritage of the area in their own hearts, informed by witnessing the slow disintegration of the industrial heart of the district. Taking their cultural heritage seriously extends, even, beyond the purview of the human, with a project undertaken recently implicating the ecological inheritance of the area in their regeneration plans. In cooperation with the Croatian Forestry Institute, the NGO instigated a project cloning the seeds of ‘600-year old linden trees from Planina Donje, a settlement at the highest altitude in the Municipality of Sesvete’ [4]. Sesvete’s locality is still not yet fully realised, but it is clear that the place still breathes with the history they carry with them both individually and in terms of the wider cultural and natural ecosystem. The work of CENTRINNO hopes to help articulate this history.

I spoke with two members of Green & Blue Sesvete, Mr. Radoslav Dumancic, and Mr. Ante Damjanovi?, both of whom have been living in Sesvete for decades, being part of the aforementioned third generation of migrants into the area in the 1990s. Indeed – it became clear after two hours of conversation in the NGO’s offices – each truly holds Sesvete close, thinking of it as home and being committed to improving the sense of community that Sesvete has. The two volunteers, who come from opposite ends of the political spectrum, prioritise Sesvete to such an extent that they put aside their political differences for the good of their home. Keeping their individual politics out of their work in Sesvete however, does not mean that Sesvete is kept out of the machinations of politics at large.

Politicising locality; localising politicisation

In 2021. a new mayor for Zagreb, Tomislav Tomaševi?, was appointed. As part of Tomaševi?’s election campaign from a centre-left position in the preceding 18 months, he conducted meetings with members of Green & Blue Sesvete and the members of the CENTRINNO project working alongside them. They met at the NGO’s office, where they also host the community chess club. In the meetings, the mayor listened enthusiastically to the proposed architectural plans about the railway-traversing connection between the ‘failed’ meat factory’s spatial boundaries and the district’s central areas [5]. His campaigning then included the public support of these plans as part of his electoral promises. This included the implementation of the new ‘general urban plan’ that incorporates Green & Blue Sesvete’s and CENTRINNO’s designs for Sesvete’s infrastructural and architectural renovation [3]. Since the election however, those plans remain to come to fruition. Having garnered significant local support for such a plan, the team remains in a deadlock thanks to the stumbling blocks of administration and bureaucracy.

Entrance to proposed new Fab Lab space

Image credit: Harry Reddick

The question, therefore, of what happens to Sesvete is clearly interlinked with the wider political developments of the Croatian capital. This may simply be a matter of resources, and how their allocation is prioritised – or not – in a city in which Sesvete is not the only area in need of development. It also could point towards the time in office for politicians being outstripped by the amount of time it takes to be held to account for all promises made on the campaign trail. The most optimistic view, meanwhile, would be that Sesvete’s brighter future is simply a matter of waiting, and that in due course these much-needed changes will come. Whatever the reality, however, Sesvete’s citizens have come to realise that, while their political views may differ, there is undoubtedly a need to be politicised in order to see the changes they hope for in the place they have called home for decades.

On-site detritus at the proposed Fab Lab that will remain until CENTRINNO’s various plans come to fruition

Image credit: Harry Reddick

Working with the heritage of places with fragmented, complicated and painful pasts becomes therefore a way to activate and draw connections between these projects of politicisation. It is vital to scratch beneath the surface, to be fully attuned to the divergent historical experiences that underpin the lived experiences of a populace in the present. Working critically and creatively with how the past surfaces in the present is at the core of the CENTRINNO heritage approach. Articulating and contextualising these experiences deeply and emotionally makes visible the reality of places like Sesvete. For Sesvete’s citizens, to be capable of putting pressure on the political bodies able to effect change, this requires a connection and a solidarity, specifically premised on this context and a personal relationship to place itself. Understanding such dynamics, of history, class, culture, ecology, politics and beyond, and how they become embedded in some sense of that slippery notion called ‘identity’, is a vital outcome of working with heritage the CENTRINNO way. Done right, these scars of the past can become paths traced towards healing.

Read more about Zagreb Pilot:

- How to build a strong local community engagement.

- Mapping of reusable resources in Zagreb.

- Fab City Hub Zagreb: a community driven hub

[1] – https://connectingnature.eu/oppla-case-study/26299

[2] – Conversation with Bojan Baletic and Roberto Vdovic, Zagreb, February 6th 2023

[5]- tportal.hr/vijesti/clanak/tomasevic-nakon-izbora-krecemo-u-izradu-novog-gup-a-za-sesvete-20210508