BLOG

Making do with the Past: Postindustrial Space and the Industrial Imaginary in Milan

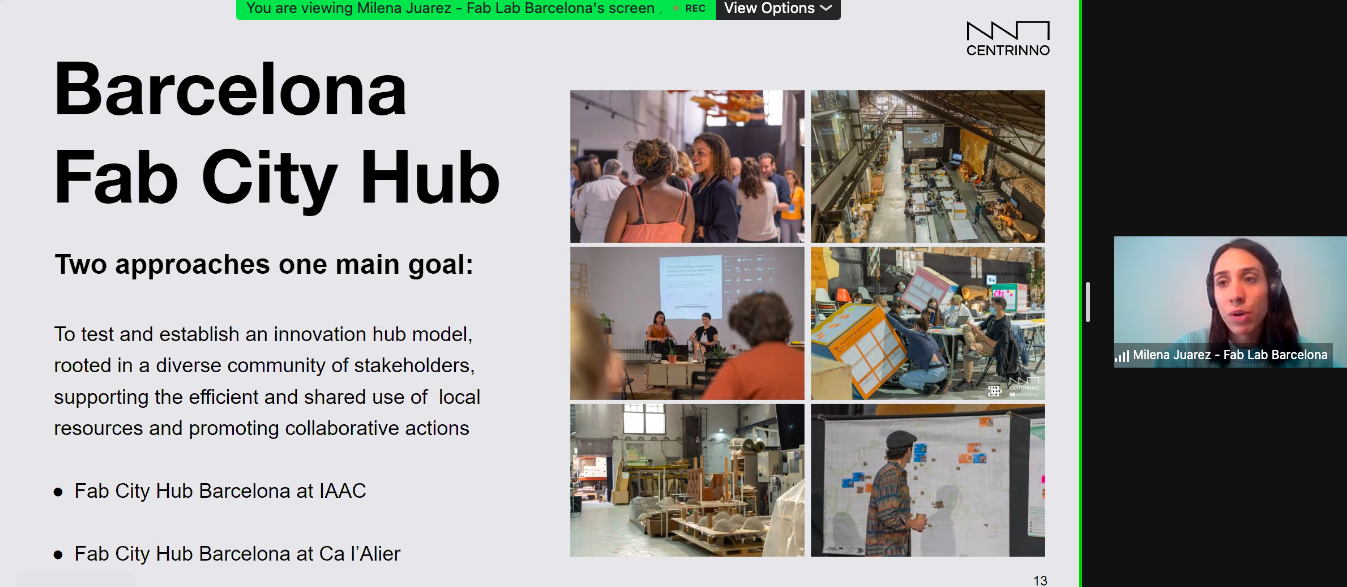

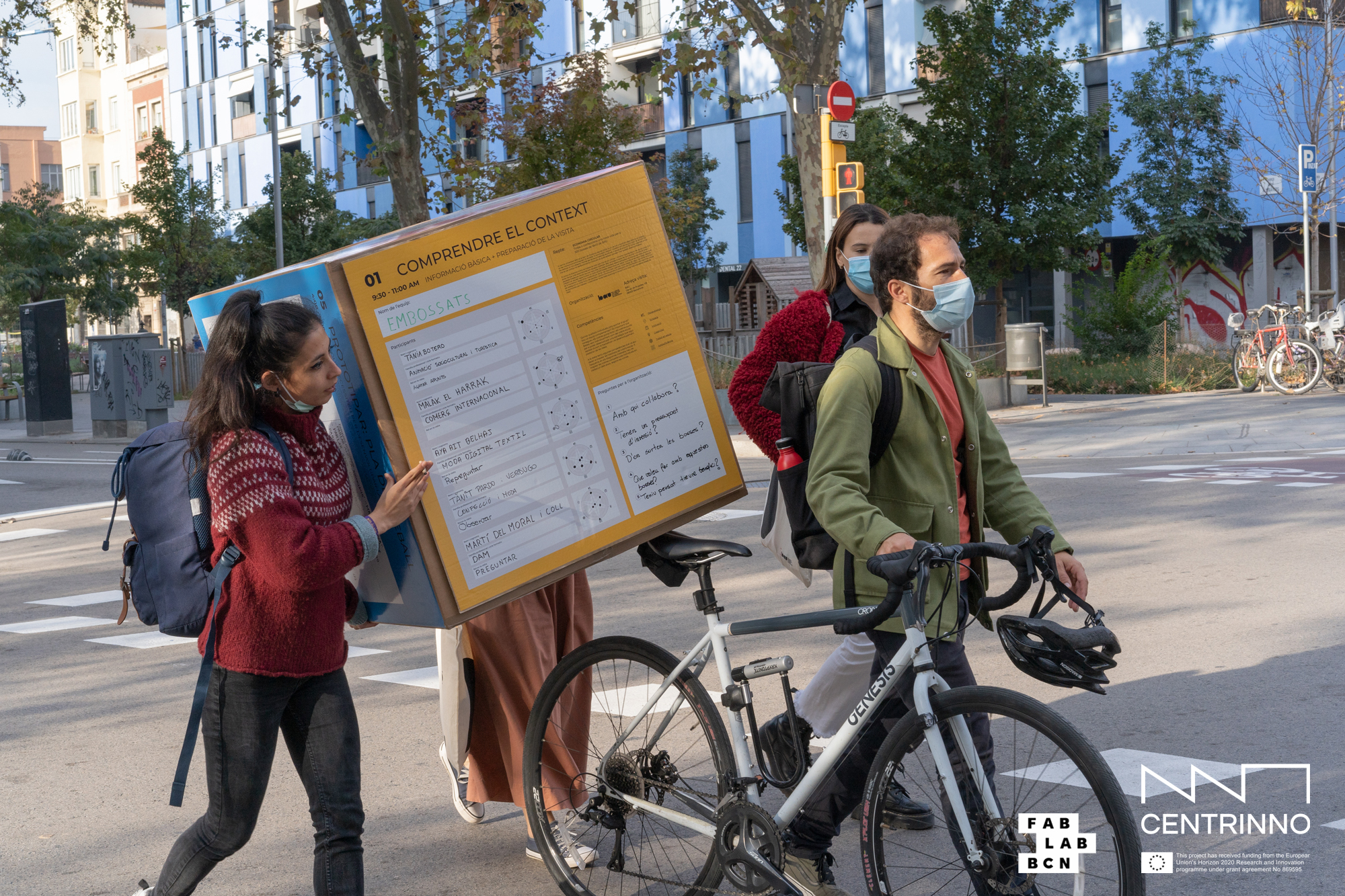

The way in which industrial space is used and reused in modern societies is a frequent source of debate amongst scholars of deindustrialisation and real estate developers alike, much as it is a fulcrum of the work being undertaken during the CENTRINNO project. In Milan, this debate is especially relevant, as a result of the transition the city has undergone in recent decades. I visited one of the globe’s key fashion locations to observe how this change has taken place.

By Harry Reddick

Fig. 1 – A model at Milan Fashion Week 2022. Image credit: Christopher Macsurak, Wikicommons

Through its status as one of the most globally-recognised fashion destinations, Milan has a reputation for the chic, the boutique, and the trendy. And understandably so: Milan Fashion Week is one of the key events in which style and material culture come together to designate and prescribe the ways in which people will express themselves through clothing for the months ahead, on a worldwide scale. The framing for this trendsetting is the catwalk, on which models elegantly display the latest designs. Extending the frame slightly further still, however, brings into focus the wider context of Milan’s historical relationship with the materiality of not just textile and fabric, but also of steel, steam, and glass. That is, of industrial manufacturing as a whole.

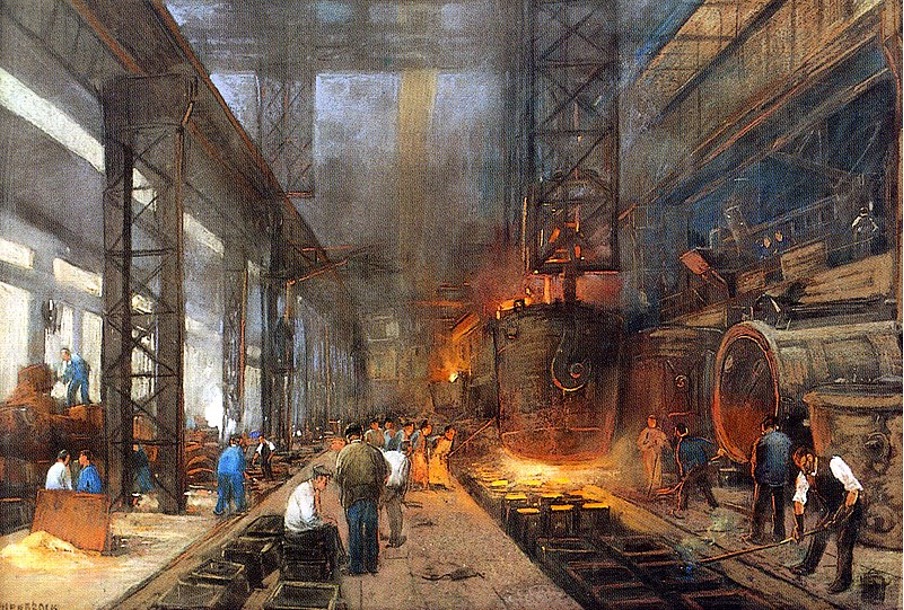

The setting for fashion catwalks in Milan is, invariably, industrial warehouses. Upon the collapse of the industrial manufacturing capacity – for example of the steelworks and train component manufacture in the former Ansaldo complex in Porta Genova, where the CENTRINNO project’s partner BASE is now located – industrial spaces fell into disuse, shorn of their capacity to make things. The establishment of the famous Italian clothing label Armani, which ‘settled…in the former Nestlé factory’, or the relocation of renowned photographer Fabrizio Ferri’s ‘studio and photographic laboratory to a former factory’, both in the Porta Genova area, are two such cases in point. [1] These spaces, characterised by heavy-set brickwork and imposing production halls, then became canvases the fashion industry could use to sketch their creative impulses upon: photography studios, film sets, and set design came together to contrast the vibrancy of the fashion industry with that of metal, sparks, and smog. A cursory google search for ‘Milan industrial spaces’ illustrates the change that has taken place in the city for the usage of space. Rather than a list of spaces in which industrial work is undertaken, what is listed are industrial spaces for rent, accompanied by terms like ‘industrial-chic’ and ‘corporate events’.

The ‘industrial imaginary’?

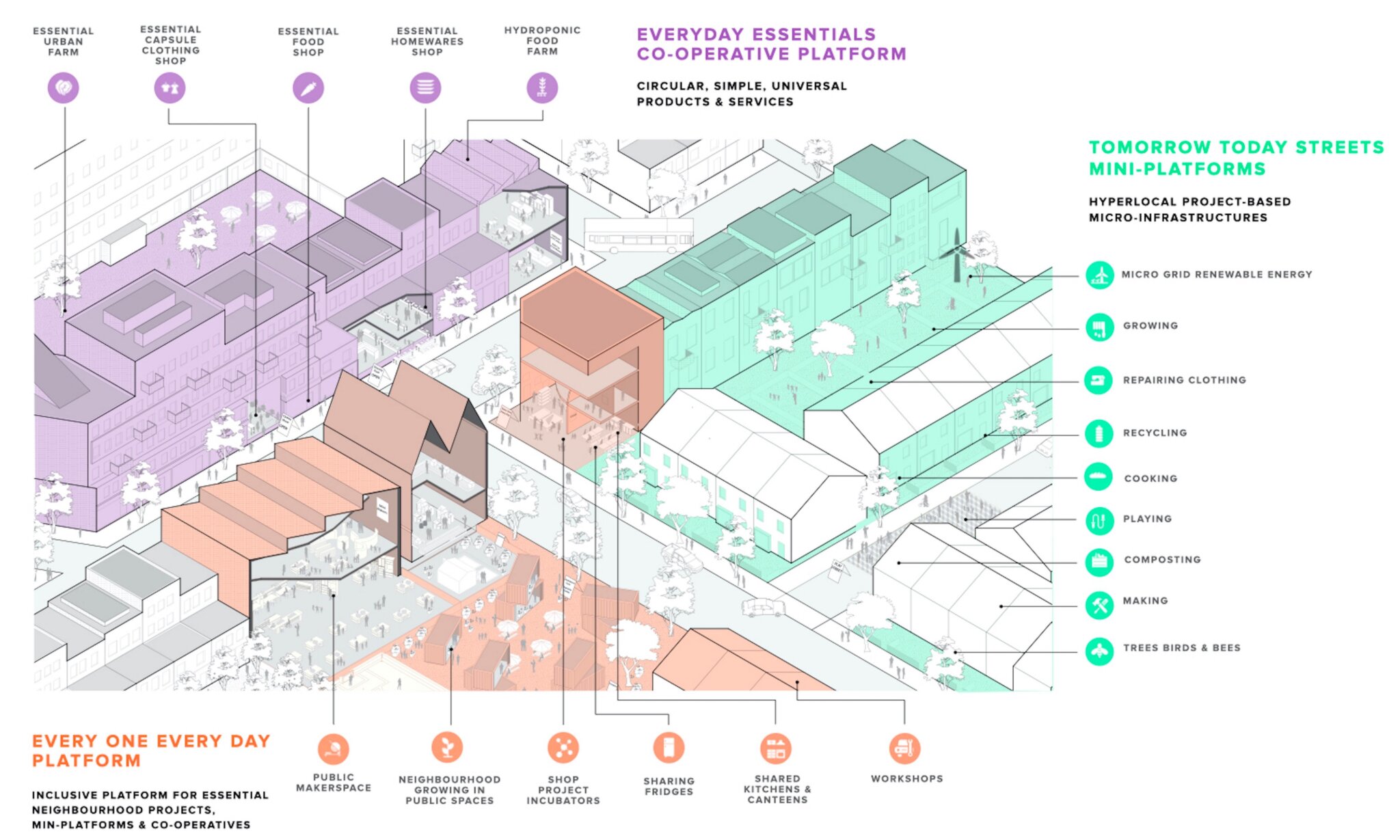

What emerges from this contrast is the ascension of a new(er) kind of conceptual and imaginative framing of Milan’s industrial spaces, while another recedes. Spaces – and labourers – whose function was to create and produce from materials on an industrial scale, became spaces and labourers for whom the act of creativity in itself was the goal: the so-called ‘creative class’. The ‘creative class’, as a result, are defined as those underpinning the forward motion of cities and regions in which ‘creativity has become the principal driving force in the[ir] growth and development’. [2] This, of course, is a transition that has played out across much of (at least) Europe’s manufacturing centres, and indeed is part of the tensions underpinning the research of the CENTRINNO project as a whole. However, in Milan, this tension is particularly pronounced, given its characterisation as one of the key ‘creative industries’ cities in Europe. [3] Such a transition could signify the movement away from what could cautiously be termed as an ‘industrial imaginary’.

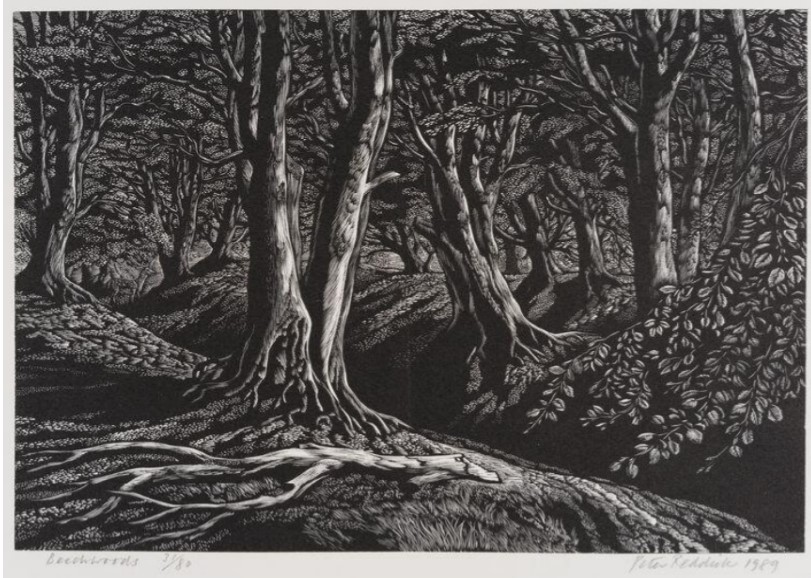

Such a term is not new, and is eminently and repeatedly problematisable beyond the realms of what can be achieved in this piece’s short scope. [see 4, 5, 6] For our purposes here I shall use it in general terms as a way of conceptualising modern life in which industrial operations are paramount. That is to say, the structuring of life according to the working day and clock time, the process of producing goods from raw materials on an industrial scale with (mostly) physical labour, the related experience of working in heavily polluting conditions, and the relationship between labourers, particularly as that intersects with the management who profit from their labour. This is an imaginary in which the perception of work is of hard labour amongst metal, oil and stone, where the smoke hangs low and where there was a collective movement to the ‘taverns, where people would replenish themselves after work’, as described in the Living Archive Story Under the Smoke of the Chimneys.

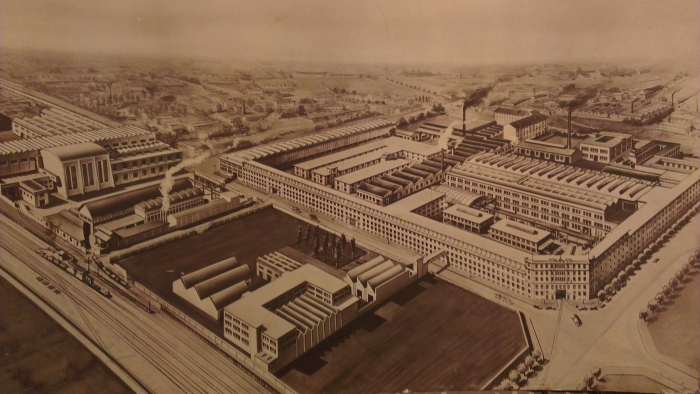

Fig. 2 – Archive image of the Ansaldo complex. Image credit: Federico Manca (Milan pilot)

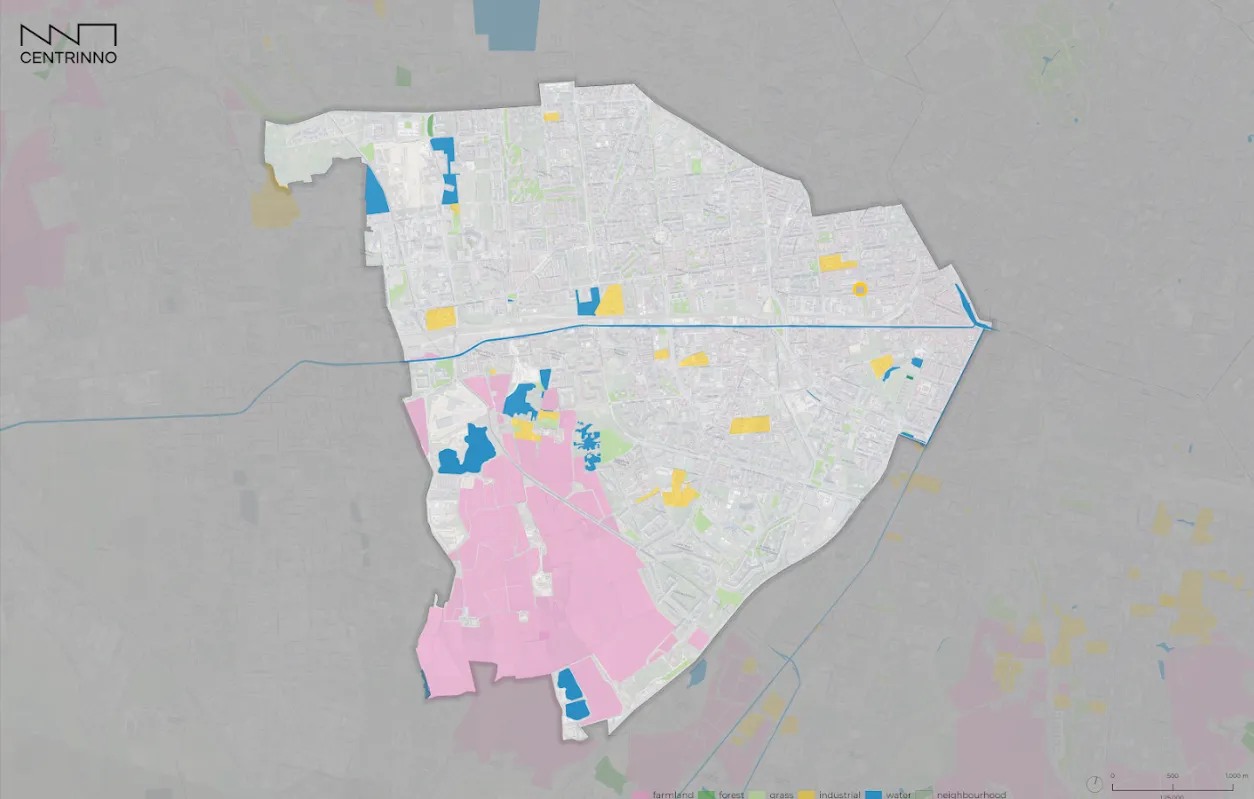

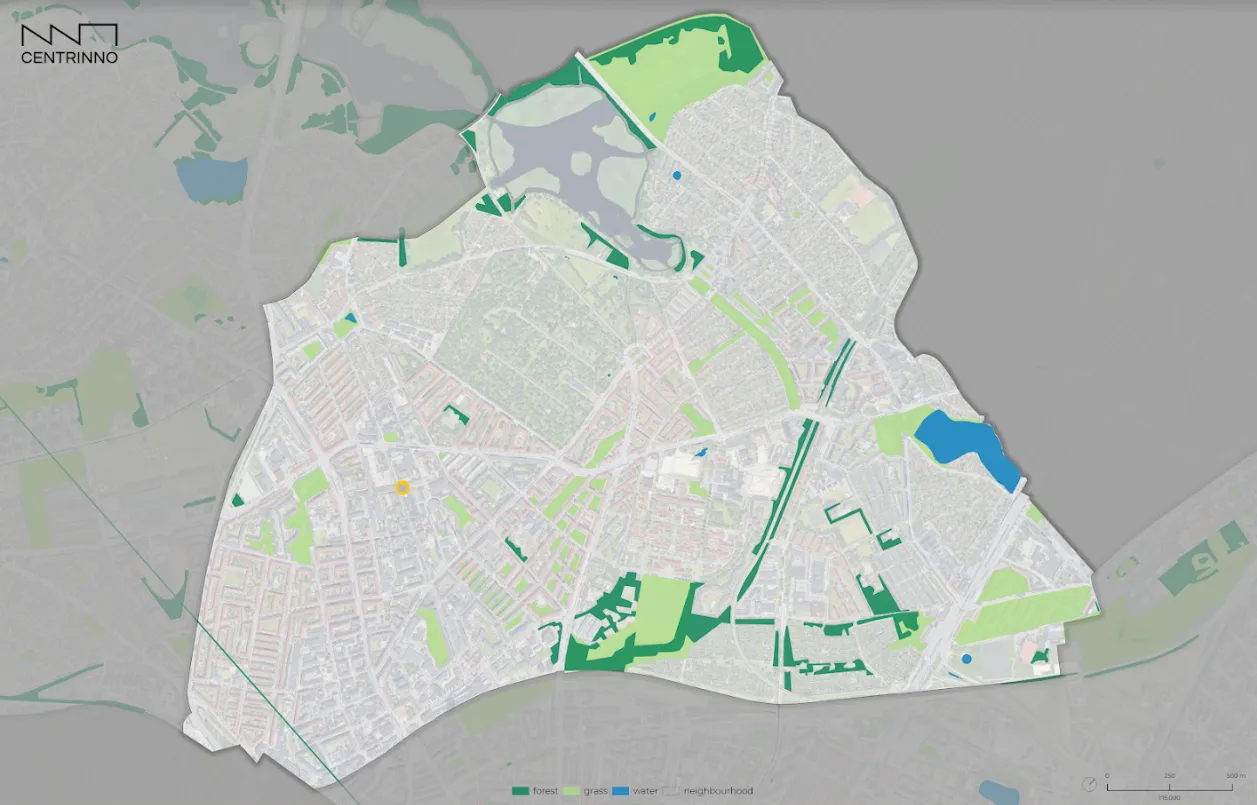

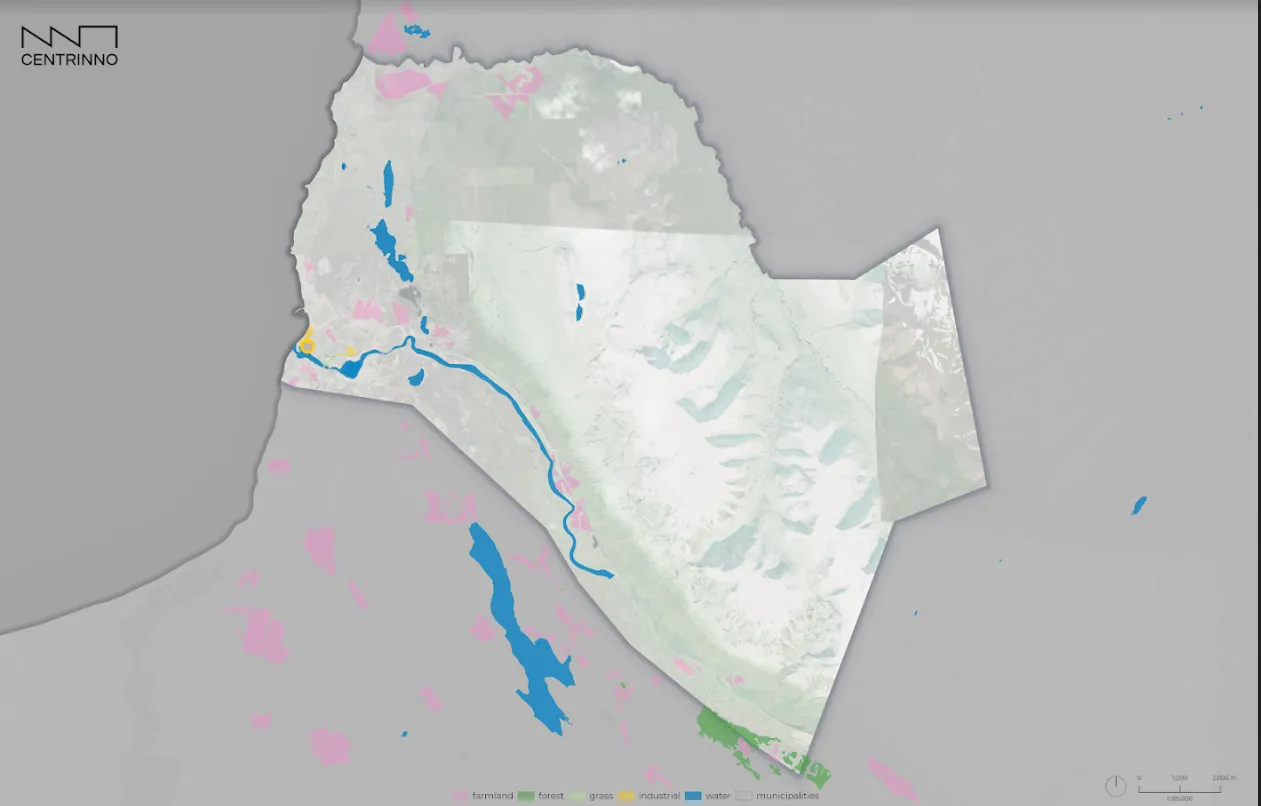

In Milan specifically, the industrial imaginary meant working with textiles and metals in huge industrial spaces dispersed both within the city and in the Milano hinterlands, connecting to other industrial centres in Turin and across Lombardy. Likewise, it meant working-class neighbourhoods with a neighbourly spirit, as well as, even after the industries began to collapse, a kind of subversive collectivism, with many squatters and activists making homes out of the former industrial spaces before they were municipally accounted for. [7] The Living Archive story The Evolution of Via Novi, for example, describes the Fabriccone, a factory that turned into the ‘embodi[ment of a new counterculture’, where ‘anarchists, mystics, and politically engaged artists emerge[d]… in the ’70s.’ In this sense, what is important about the industrial imaginary is the way in which aesthetics conjure up certain associations from the past that permeate and affect the present, what narratives can be made about industrial places, and the associated capacity for meaning-making therein. This goes beyond merely association: Giovanna Fossa demonstrates that municipal planning designates that ‘creative re-uses (showrooms, workshops…exhibition spaces…etc) are interpreted as ‘industries’ by the City Planning Department’ to circumvent lengthy zoning change regulations, even though they don’t hold the same function as when such laws were implemented. [1] Evidently, the idea of industry stays with spaces even after the industrial activity in it has ceased, at least in some important areas such as public policy.

To see how the effect of this notion plays out in the modern day, reimagined industrial spaces of Milan, I visited some different former industrial spaces with a variety of reuse functions. Across the three different approaches used by BASE (and its Porta Genova surroundings) itself – as well as Fondazione Prada, the modern art museum located in Milan’s south-eastern quarter, and the former steam factory Fabbrica del Vapore in Milano north – the way in which the imaginary effect of the industrial era can be understood to intersect (or not) with the modern face of Milan, started to become clear. In doing so, industrial heritage and a postindustrial future appear as irreversibly tangled and complicated by one another.

A break from the past: Fabbrica del Vapore

Fig. 3 – The ‘cathedral’ space within Fabbrica del Vapore. Image credit: Fabbrica del Vapore

The Fabbrica del Vapore (‘The Steam Factory’) complex comprises the remaining structures of what was once ‘an industrial area and home to the historic Carminati Toselli manufacturer of tram and railway rolling stock.’ According to the complex’s website, ‘the factory has been renovated, recovered and given a new life starting from the new millennium.’ [8] The life that has been left behind is outlined in the section ‘La Storia’, which explains how Carminati Toselli, from 1899, ‘dedicated itself to the “construction, repair and sale of movable and fixed materials for railways, tramways…”’. The company developed into a more significant entity over the following twenty years, being a key part in the expansion of the Milanese tram network from 99 km of track and 125 trams ‘circulating every day’ in 1886, to 150 km of track and 700 trams in 1926. By 1935, and in connection with the seizing of power by the fascist regime, the company dissolved, with the space being described as used in various ways for ‘textile and pharmaceutical industries, typography, road haulage and various deposits’ until its current iteration. [9] Now a municipally-funded ‘place for the implementation of interventions to promote youth creativity, entertainment and aggregation’, the space is home to a number of inclusive projects aiming to encourage integration and artistic endeavours, such as The Art Land and SPINOff. [10, 11] The well-meaning nature of these projects notwithstanding, the case of Fabbrica del Vapore illuminates some further complexities. How much does the industrial imaginary persist here, for example?

The complex at Fabbrica del Vapore is visually defined by classically-recognisable industrial architecture. Warehouse facades are maintained in all their imposing glory, with large squarely-divided windows set amongst uniform brickwork. Inside the on-site bar, ‘Vapore 1928’ (why it references this date is not clear), exposed piping lines the walls, and steel girders cross the rafters. The image of industry is clearly still present, and is part of the presentation of the entire space. Indeed, this is evidently the focal point of the aesthetic strategy utilised in the site’s reuse. It looks cool to design – or retain elements of a previous design – in this way.

Despite its appearance however, the space is not a site of industrial production. These warehouses, as discussed, are not full of machines still manufacturing railway components or the doors of trams, much less the production lines populated by industrial workers operating said machines. Their labour is at the heart of the history of this space, and yet the space barely makes reference to the workers. The passing comment on the companies as a whole, mentioned in the ‘La Storia’ section of the website, comprises the bulk of mentions of the site’s former manufacturing capacity. As a result, no individual workers are historically recognised: only the overarching private enterprise their labour supported are given space in the story.

The industrial imaginary then, is produced in aesthetics, purely on a surface level. Illustrating this further is the treatment of the surrounding area in the transition. Situated on the ground floor of what is now the expensive VIU Hotel Milan, just opposite the Vapore complex, is the Bulk Mixology Food Bar. While in this instance, any reference to industry is completely removed, in favour of the polished aesthetic of foodie culture, the location is notable because of the space’s history as a squat, in direct proximity to and in connection with the former industrial complex.

Before its demolition to make way for the sleek facade of the hotel, the squat was an active anarchist space of creativity, making, and subversion, keeping alive the aspects of industrial life that prioritised community and craft, alongside a political focus on alternative cultural production. These artists present in the squat were not, however, offered the opportunity to move their operations into the premises at Vapore, with the municipality preferring instead to work with creatives with a ‘cleaner’ and ‘safer’ image, as one of the former squatters told me. [12] There was even a bar in the squat, also named Bulk. That the new space effectively architecturally and socially sanitised the creative and community-orientated ethos of the squat, whilst retaining the name, speaks to the hollow nature of the wider invocation of the industrial imaginary, and the pitfalls of certain development strategies which seek to reuse industrial space without paying the necessary attention to the industrial past itself.

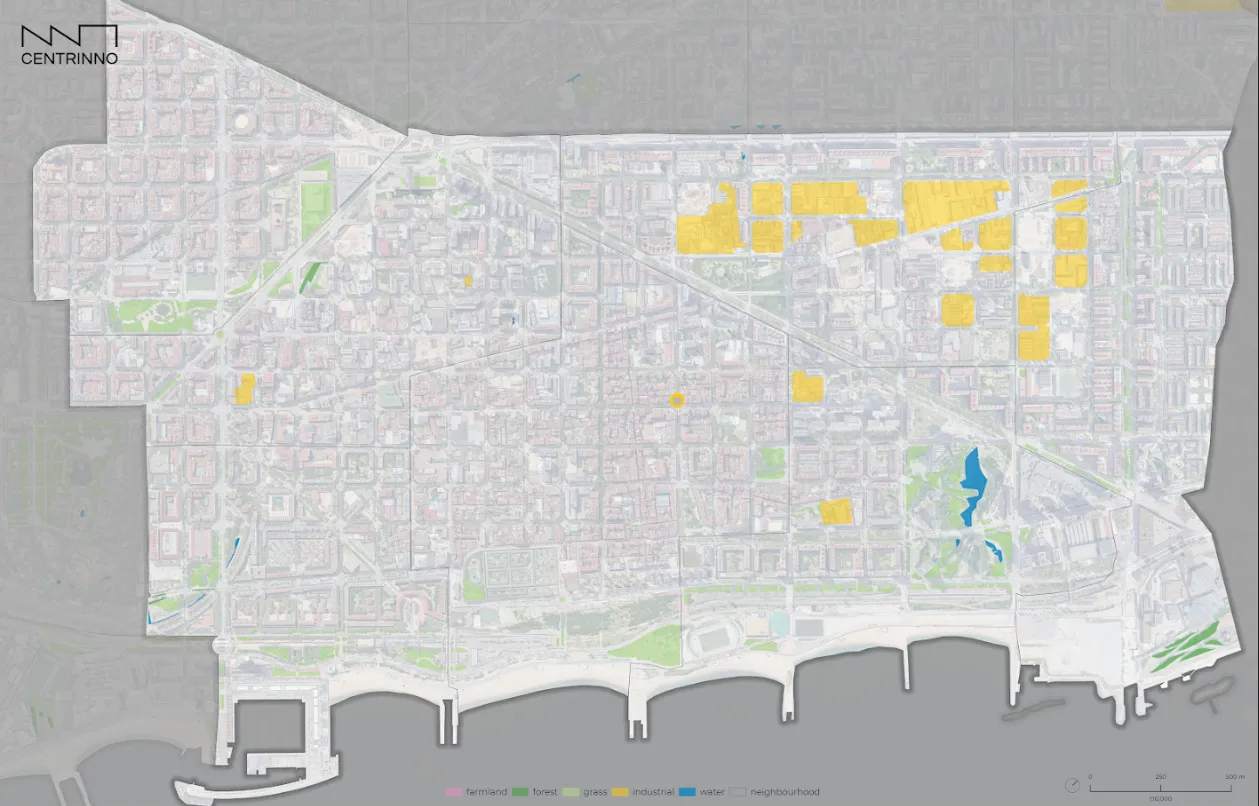

Sidestepping the Postindustrial: Fondazione Prada

A sprawling art museum complex with a 19,000m total footprint, situated across several different buildings making up a former distillery, the Fondazione Prada art gallery takes a quite different approach to the utilising of a postindustrial space. As described on the museum’s website, Fondazione Prada is ‘characterized by an articulated architectural configuration which combines seven existing buildings with three new structures (Podium, Cinema and Torre).’ Indeed, as head architect of the design, Rem Koolhaas describes: ‘The Fondazione is not a preservation project and not a new architecture. Two conditions that are usually kept separate here confront each other in a state of permanent interaction’. [13] This interaction extends to the programming of the museum itself, with the ‘Haunted House’ installation of Robert Gober and Louise Bourgeois’ work an ‘enhance[ment]’ of the original distillery structure, with large ‘windows highlight[ing] a strong relationship with the external landscape and the adjacent buildings’, while maintaining ‘an intimate spatial scale’. [14] The allure of the Fondazione Prada then, is found in its placing the new and the old into an ongoing architectural and artistic conversation and confrontation, in which temporal moments begin to blur and fold, ouroboros-like, into one another.

Where does that leave us in terms of the use of former industrial spaces as reimagined, reinvented, and reused spaces? Is this even a postindustrial space? What are the characteristics of that word – ‘post’ – when it comes to this kind of architectural intervention? Certainly this is a manifestation of space after its time as a space of industrial work. But the way in which the industrial imaginary lingers upon the complex implies a different relationship with the aesthetics of industry. Upon arrival into the Fondazione Prada space, or even when passing through the surrounding area, there are recognisably industrial structures, such as the pointed-roof large warehouse format shown in Fig. 5, that one can see from outside the southernmost exterior of the site. However, upon entering the site, the sense of industriality begins to rapidly distort. The adjoining structure between separate exhibition spaces, depicted in Fig. 6, coated in grey granite and supported by chrome columns, belongs much more to the aesthetic of an art gallery than of a remembered industrial site.

Fig. 5 – The outermost exterior wall facing south. Image credit: Harry Reddick

Fig. 6 – Inside the Fondazione Prada complex. Image credit: Harry Reddick

It would be difficult to say that the industrial imaginary is noticeably present within Fondazione Prada, in the sense that it is rather a place of continual reinvention of its own aesthetic boundaries and reference points. That said, the crucial difference, to my mind, is that the space makes no claims upon such a history by retaining clearly-recognisable industrial aesthetics. This may seem like an irrelevance: after all, why mention it at all if it is simply a completely different use of an industrial space? Where I think a subtle – but important – distinction lies however, is in the fact that, unlike the VIU Hotel on the outskirts of the Vapore complex, this is not a complete reconstruction, but instead, as Koolhaas stated, a combination of retention of old and addition of new structures. In this sense, an element of industrial fabric remains, but without the appearance of being industrial. A good example of this is the ‘Haunted House’, shown in Fig.7, which sees the entire former distillery structure coated in a sheet of vibrant gold leaf. One does not see such a building and find themselves immediately drawn into industrial-era reverie. Likewise, one does not enter the Prada complex and get a sense of the industrial past, or even solely of an art space. Rather, it exists somewhere peculiarly in-between, as in intervention into the idea of industrial spatial reuse, with a different agenda than simply emptily reproducing the absent past.

Fig. 7 – The Haunted House (top right), inside the Fondazione Prada complex. Image credit: Fondazione Prada

Creative-industriality at BASE and Porta Genova

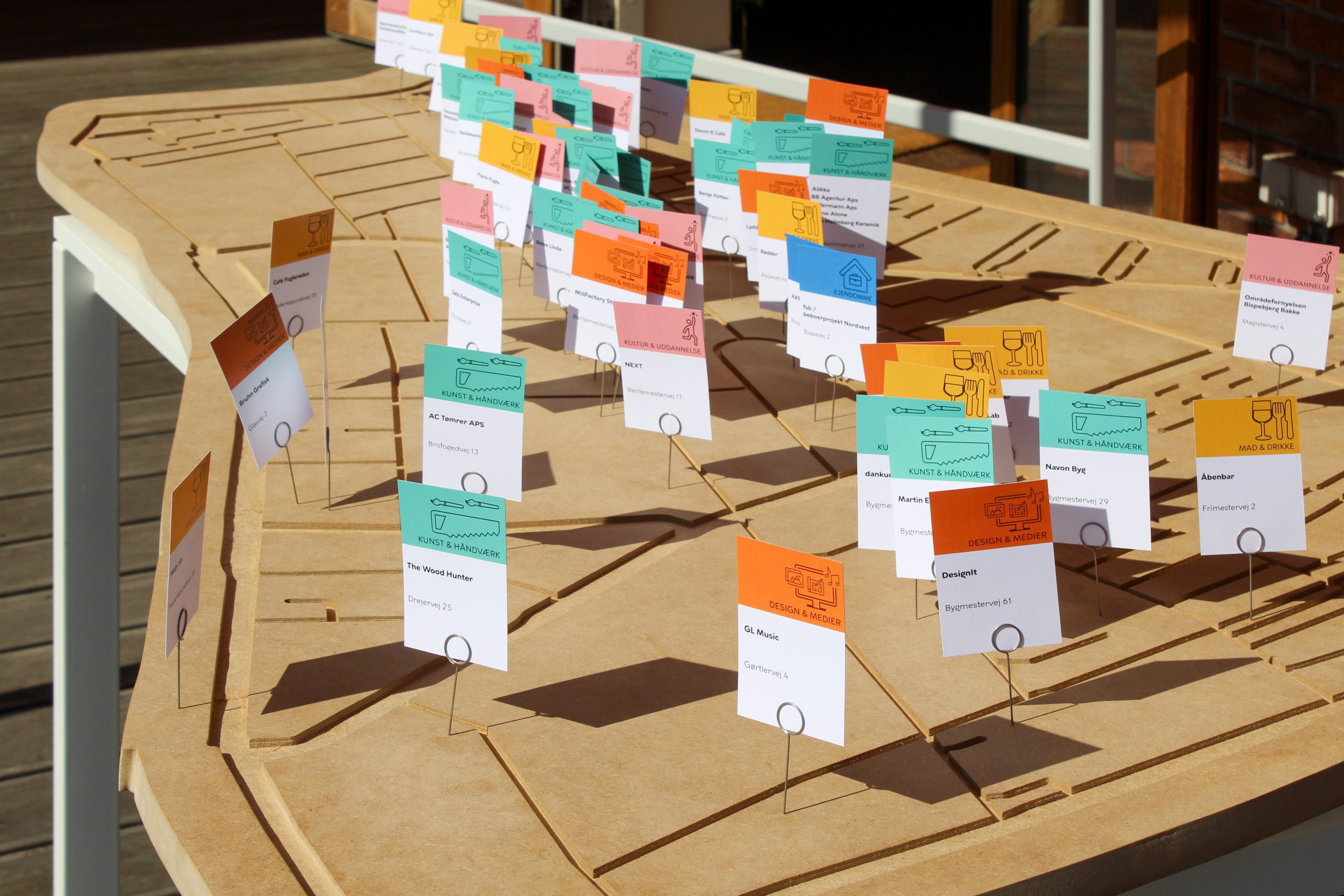

The BASE complex is, according to the organisation’s website, a ‘hybrid cultural centre to serve the city,’ [15] and is elsewhere described as ‘the new project for the culture and creativity of the Lombardy capital which brings the over 6000 square meters of the former Ansaldo to life.’ [16] In order to explore the relationship between what is now BASE, the focal point of the CENTRINNO pilot in Milan, and the idea of the industrial imaginary, it is necessary to situate it within the wider context of the Porta Genova area. This is particularly relevant given that the Living Archive stories from the Milan pilot are sourced not only from the Ansaldo factory, but also in the neighbouring streets.

Fig. 8 – Entrance to the BASE Milano complex.

BASE’s spatial footprint makes up a large chunk of the the Porta Genova area, a ‘wide industrial neighbourhood (about 2 km long and 500 m wide) [that was] born at the end of the 19th century…and is bordered by the railway line that runs along the Naviglio Grande Canal.’ [1] The result of a long and speculative debate ‘inside and outside the Municipal Administration’ of Milan, BASE is the culmination of over a century of industrial activity. Construction of the factory began in 1904 and was completed in 1923, before ‘initially becoming the headquarters of the Roberto Zust company and then being purchased by Ansaldo in the mid-1960s…[where the company had] produc[ed] locomotives, railway carriages and tramways for over thirty years.’ Becoming a municipal property in 1989, the former-Ansaldo factory serves as one of the key architectural landmarks in a ‘neighbourhood that has experienced a profound transformation in recent years, moving from the industrial vocation that has characterized it since the 1960s to a creative one.’ [16] The recent opening of the Museum of Extra-European Cultures, with an eye-catching design within the factory’s salvaged built structures by world famous architect David Chipperfield, underlines this transformation.

As shown in Fig. 8, The large opening leading to BASE’s interior has the words ‘The future is an invisible playground’ adorned above it, an installation developed by artist and sculptor Robert Montgomery. [17] Such a provocation speaks not only to the change to a ‘creative’ zone referenced above, but also to the forward-facing mindset embodied by the cluster of organisations calling it home today. To (poetically) make reference to the unknowability of the future appears at first glance the kind of perspective that we have seen constitutes a break from the past that marginalises the industrial history present in the space. There is, I would argue, some validity to this argument with regards BASE’s present-day conception, given the well-trodden pathway of industrial space transformed into creative space, explored here and elsewhere. This is precisely where the work of the CENTRINNO project comes in.

With former industrial workers less present (or indeed, completely absent) in the day-to-day operations of BASE itself, the collecting of stories for the Living Archive provide a platform for their voices to be heard, and the implications of their labour to be understood, and threaded amongst the work done by the premises’ current occupants. Central to this is the theme of making. Pietro, the protagonist of the story Under the Smoke of the Chimneys, ‘spent most of [his] life in that factory, skillfully and dedicatedly working with metals… surrounded by the melody of machinery and the warmth of the blast furnaces.’ Guiseppe’s story Handcrafted Straw Hats meanwhile, speaks of gaining respect amongst his peers when ‘started to work in the family business [of making straw hats] at the age of thirteen’, following in the footsteps of his ‘grandfather [who] had started as a worker many years before.’ The business also produced ‘colonial hats’ at a certain point, complicating further the legacy of industrial production in the 20th century by situating this labour within the wider web of colonial international relations that still resonates painfully and significantly today. To uncritically present the industrial era – without these complex, structural and relational stains upon historical memory – would be to undermine the necessary work of heritage as it is undertaken within CENTRINNO.

In the post-industrial period, further stories illuminate further aspects of the complexities of the BASE complex’s heritage. The story A Wonderful Place finds Carlo Traviganti recounting his experience amongst a group of craftsmen working with precious metal (having moved into the same former ‘anarchist social center’ described earlier on) on the cusp of the 1980s. Alfredo meanwhile, telling what happened Among the Shadows of Time, describes ‘streets [that] resounded with the sounds of machines and workers going back and forth’ during the bustling industrial period. Returning to the area many decades later, Alfredo finds it a shell of its former self, with an accompanying ‘sense of loss’ for a neighbourhood that ‘seemed empty, deprived of its soul.’

Difficult past(s), different future(s)

The sense of loss in Alfredo’s story perfectly captures the tensions that persist in industrial spaces. Between rose-tinted nostalgia (of which, within the Milan pilot stories, there is a lot), and the pain of the industrial community’s dissolution, stand the many complex iterations of heritage generated by the logic of the industrial era. It is through this aspect of the translation of the BASE historical fabric into stories within the Living Archive that the industrial imaginary remains present within the Milan pilot site. That is not to suggest that the BASE approach is beyond criticism: there are a few problematisable aspects to both the tone and the reach of the stories collected. However, what is vital about the heritage work undertaken here is illustrated in two key points. Firstly, the fact that the space remains a place of making, just with some differences in output in accordance with the altered needs of the present (the pilot’s partnership with another Milan makerspace, OpenDot, assists with this makership capacity), and the associated social shift towards the creative industries. The second – and perhaps most important – aspect is the way that the industrial imaginary is evoked not just through workers’ stories, but in the bringing forth of the entire trajectory of industrial space, from manufacture, to deindustrialisation, to creative reuse, and finally to memory, which swims back and forth amongst all these other historical moments. As discussed earlier, this is a trajectory with both a more general set of characteristics, and a Milanese specificity.

This historical trajectory is evidently full of contradictions, painful moments, shifting balances of power, blossoming solidarities, new beginnings, environmental abuses, demographic change, migration patterns, sociopolitical developments, and more besides. Parsing the most ethical route out of such a tangled web of relations is an arduous and complex task. But whoever suggested it would be easy? The heritage work in CENTRINNO exists precisely as a way to tease out the most socially-inclusive, sustainable, and circularity-promoting aspects of the past, and with such an approach, a path towards a brighter future for and via historically-tensioned places like BASE, might well be possible.

References

[1] Giovanna Fossa, ‘Milan: Creative Industries and the Uses of Heritage’, in Heike Oevermann and Harald A. Mieg (eds.), Industrial Heritage Sites in Transformation: Clash of Discourses, (New York: Routledge, 2015), 69.

[2] Richard Florida, Cities and the Creative Class, (New York: Routledge, 2004), 1.

[3] Cheng Shen, Xinyi Zhang, and Xiang Li, ‘The development of global creative centers from a regional perspective: A case study of Milan’s creative industries’, PLoS ONE, vol. 18 no. 4, (2023), e0281937, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281937

[4] The industrial imaginary in relation to the Victorian cultural psyche is explored in: Tamara Ketabgian, The Lives of Machines: The Industrial Imaginary in Victorian Literature and Culture, (Detroit: University of Michigan Press, 2011).

[5] The industrial imaginary is also evoked as a way of understanding the total reconstruction of modernity according to the lines drawn between time, production, profit, and data, in: Iris M. Zavala, ‘The Industrial Imaginary of Modernity: The “Totalizing” Gaze’, in A.L. Geist (ed.), Modernism and Its Margins: Reinscribing Cultural Modernity from Spain and Latin America (New York: Routledge, 1999).

[6] The field of deindustrialisation is rightly critical of various applications of an industrialising aesthetic when using it in a nostalgic and uncritical way. Some important texts delineating this critique are: Tim Strangleman, ‘“Smokestack Nostalgia,” “Ruin Porn” or Working-Class Obituary: The Role and Meaning of Deindustrial Representation’, International Labor and Working-Class History, vol. 84, no. 1, (December 2013), 23-37., and David Lewis and Steven High, Corporate Wasteland: The Landscape and Memory of Deindustrialization, (Toronto: Between The Lines Publishers, 2009).

[7] This point was raised via a conversation I had with Marianna D’Ovidio, associate professor in Urban and Environmental Sociology at the Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca, and Milan pilot team member (and former squatter-activist) Zoe Romano on October 11th 2023. Marianna had previously experienced the neighbourhood support in an industrial neighbourhood, and witnessed first-hand its slow erosion from the local area.

[8] Text translated from Italian using Google Translate. Unknown author, ‘Homepage’, Fabricca Del Vapore, https://www.fabbricadelvapore.org/ accessed 25th October 2023

[9] Text translated from Italian using Google Translate. Unknown author, ‘La Storia’, Fabricca Del Vapore, https://www.comune.milano.it/web/fabbrica-del-vapore/la-storia, accessed 25th October 2023

[10] Text translated from Italian using Google Translate. Unknown author, ‘Chi Siamo’, Fabricca Del Vapore, https://www.comune.milano.it/web/fabbrica-del-vapore/chi-siamo, accessed 25th October 2023

[11] Text translated from Italian using Google Translate. Unknown author, ‘Laboratori Creativi’, Fabricca Del Vapore, https://www.fabbricadelvapore.org/laboratori-creativi. accessed 25th October 2023

[12] As per conversations I had with former squatter of the space, who shall remain anonymous for their privacy.

[13] Unknown author, ‘Visit Milan’, Fondazione Prada, accessed at https://www.fondazioneprada.org/visit/visit-milan/?lang=en, accessed 30th October 2023.

[14] Unknown author, ‘Robert Gober / Louise Bourgeois’, Fondazione Prada, accessed at https://www.fondazioneprada.org/project/louise-bourgeois/?lang=en , accessed 6th November 2023.

[15] Unknown author, ‘Home’, BASE Milano, unknown publication date, accessed at https://base.milano.it/en/ on 6th November 2023.

[16] Text translated from Italian using Google Translate. Francesca Vittori, ‘BASE MILANO. NUOVE FONDAMENTA PER L’INNOVAZIONE CULTURALE’, Il Giornale delle Fondazioni, published 15th April 2016 at www.ilgiornaledellefondazioni.com/content/base-milano-nuove-«fondamenta»-linnovazione-culturale#:~:text=Lo%20stabilimento%20è%20stato%20costruito,locomotive%2C%20carrozze%20ferroviarie%20e%20tramviarie accessed 6th November 2023

[17] Guilia guido, ‘The light poem by Robert Montgomery’, Collater.al, published 2020, accessed at https://www.collater.al/en/robert-montgomery-base-milano-installation/ on 8th november 2023