BLOG

Pollinating the industrial past: The role of bee(keeper)s in Kopli 93

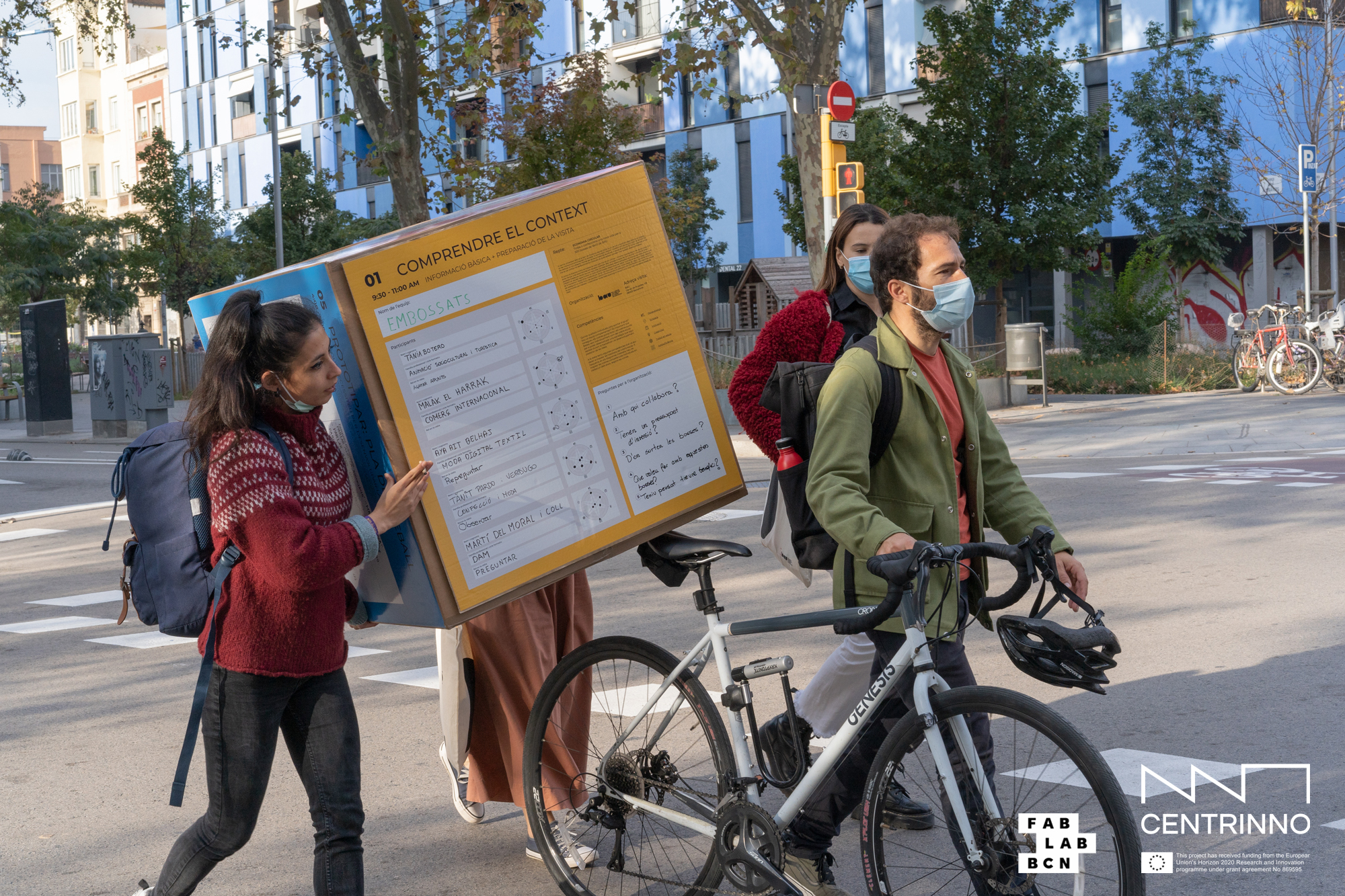

Within the CENTRINNO project, the research partners consider heritage an approach through which we can understand the complexities of the present.. In this blog post, Harry Reddick from the Reinwardt Academy spoke with the Tallinn pilot team, as well as a beekeeper from Tallinn, about what bees can teach us about how to build upon the events of the industrial past, and work towards a brighter, more inclusive future.

Photo credit: Elo Strauss via CENTRINNO Living Archive

A cross-pollinated awareness

‘I experience climate change, already’, says Karin Kruup, one of the members of the Tallinn pilot team from the CENTRINNO project. While there are innumerable different ways in which this could be experienced on an individual level, perhaps it is indeed from direct experience that the reality of a heating planet can be best understood. (Certainly this is the case in locations in the global south, many of which have already experienced ‘the end of the world’ that climate change discourse promulgates [1]). For Karin, it comes – at least in part – from her recent experiences beginning to learn about how to keep bees. Long since understood as one of the most vital parts of a healthy ecosystem, bees are now often cited as one of the imminent casualties of a climate set to change drastically in the near future, with potentially disastrous results.[2] [3] Speaking with the Tallinn pilot, as well as the Tallinn-based beekeeper Erki Naumanis who has been providing guidance in the local apiaries, it became clear that the behaviour and populations of bees provide vital insights not only for navigating what is to come, but also for how the Estonian capital as it is today came to be(e).

Erki himself started beekeeping around 2009, having ‘caught the bug’ when observing the nearby apiaries near his workplace in New Zealand, before returning to Estonia and begin his tutelage under a local, 82-year old (!) beekeeper. In 2016, having moved closer to Tallinn, he took over and made official the Estonian Beekeepers Association. Since returning to Tallinn, Erki has been a key figure among beekeeping enthusiasts across the country who look after beehives and their populations, keeping a keen eye on how these anthophiles reflect changes in the varied political and urban ecologies of Estonian cities. He also spends time convening with the international beekeeping community, whether via conversations about the pros and cons of traditional versus standardised beekeeping frames, or by listening to podcasts from beekeepers abroad.

Photo credit: Evelin Susi via Eesti Mesinike Liit

As part of the work undertaken by the CENTRINNO project in Kopli 93, children under Erki’s supervision regularly undertake visits to the Kopli beehives, which are full of docile bees that will ‘walk on your hands’. Far from the ‘hot hives’ that Erki started working with, which have previously found him ‘running into the lake’ to protect himself from swarms of defensive bees, the bees in Kopli are the perfect phenomena with which children can engage in order to begin to learn about and feel connection with the natural world. As well as the necessary caution when interacting with bees, Erki says that the main requirement when visiting the apiary – whether for the children or for the beekeepers – is that people ‘must bring happiness with them’. This could also be understood a different way: it may indeed be that learning with curiosity about these creatures is simply a joyous process. And why shouldn’t it be? Bees are a marvel of ingenuity, serving in many ways as the connective tissue of the ecosystem which they themselves cultivate, which provide a variety of insights into the sustainability goals of the CENTRINNO project.

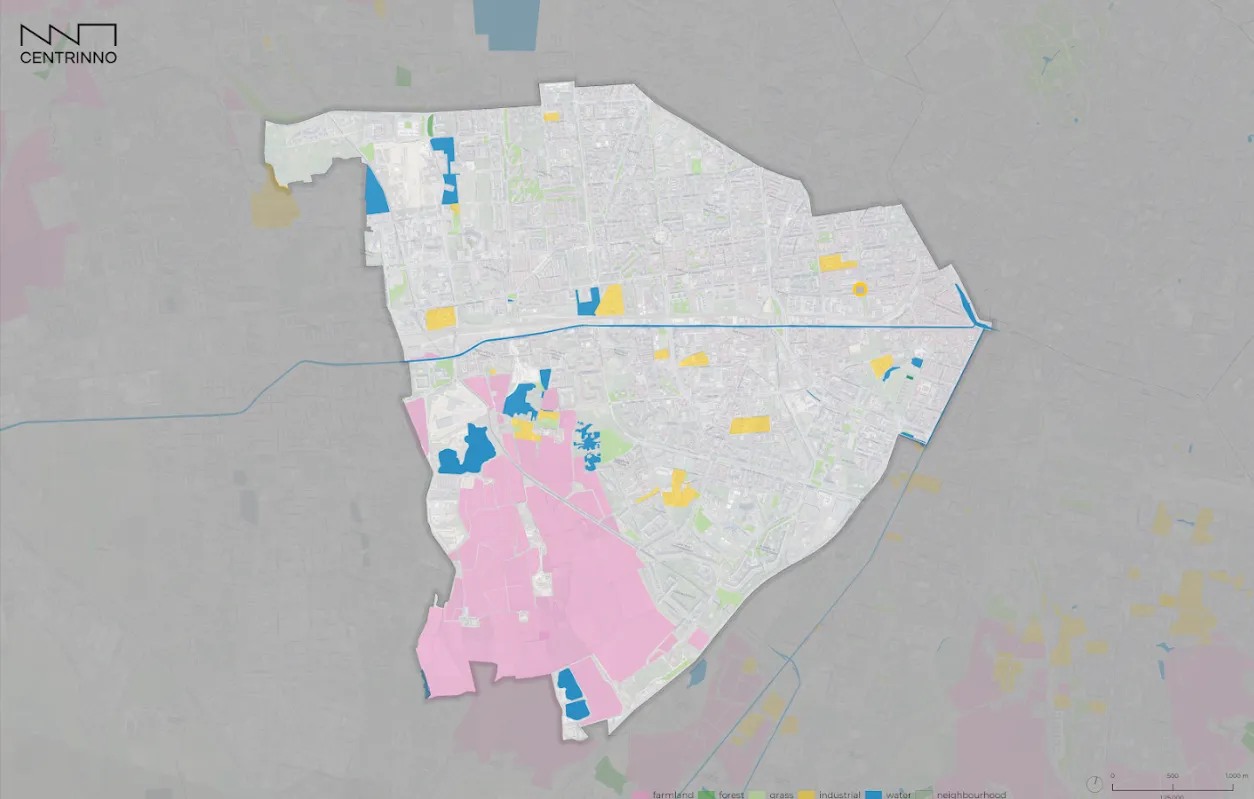

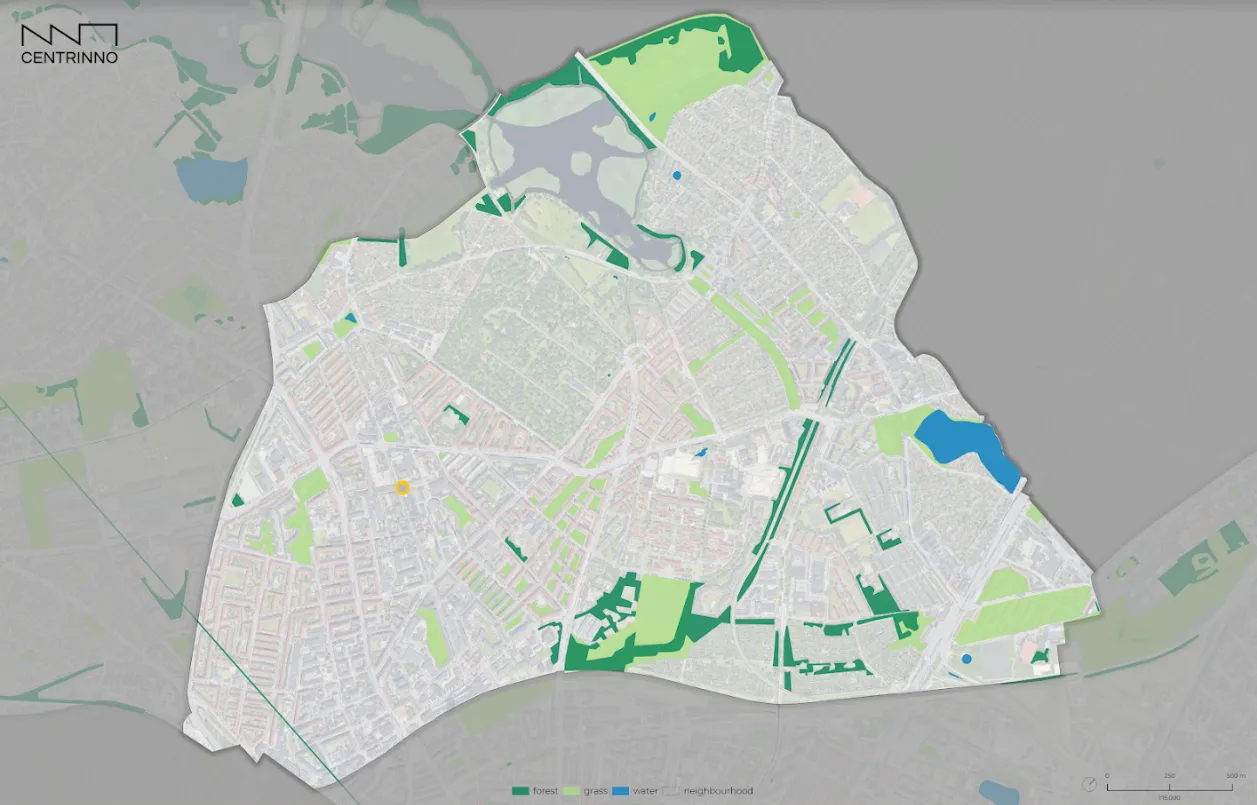

The thriving gardens of Kopli

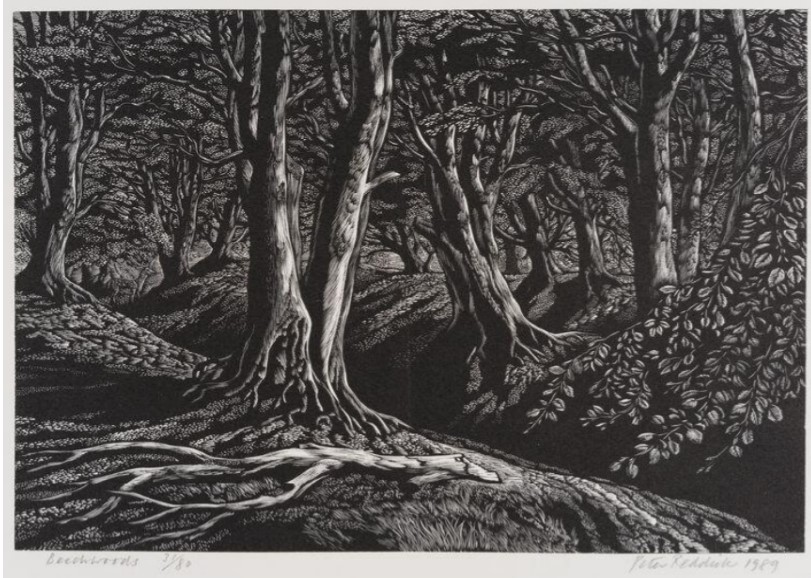

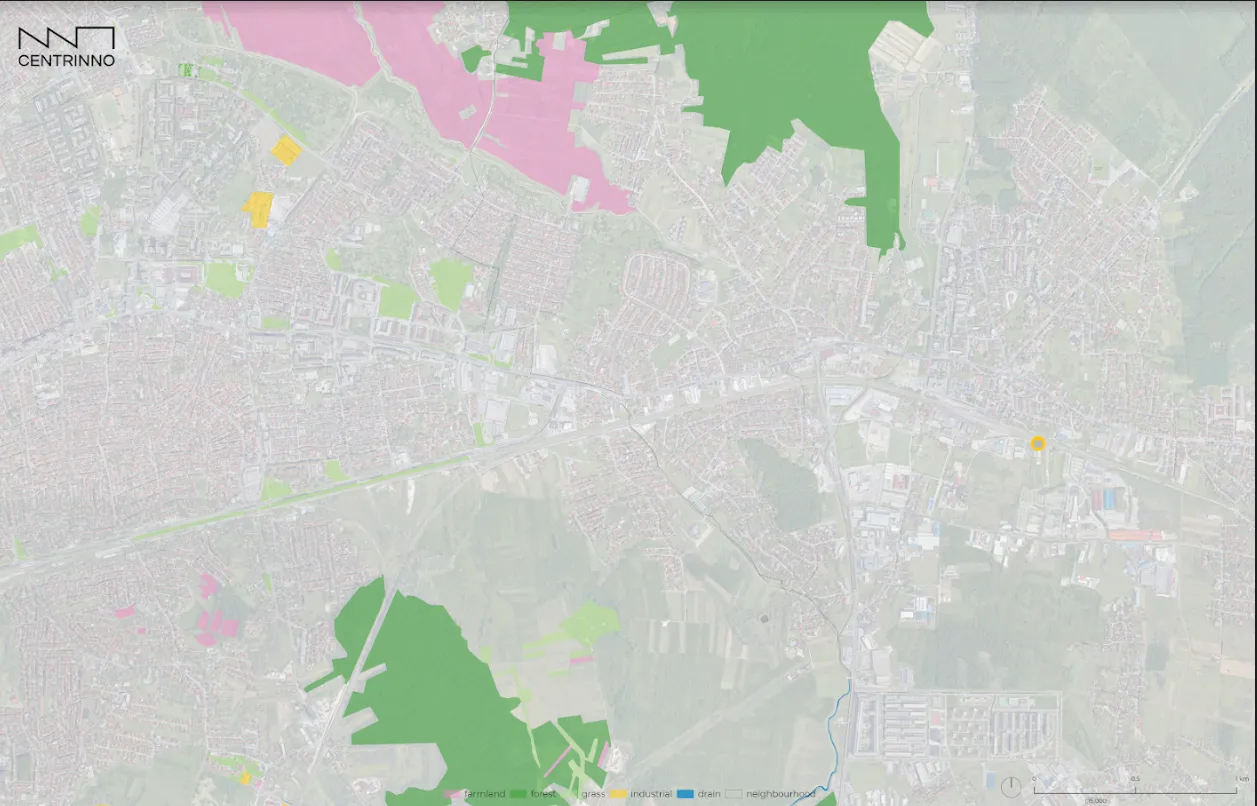

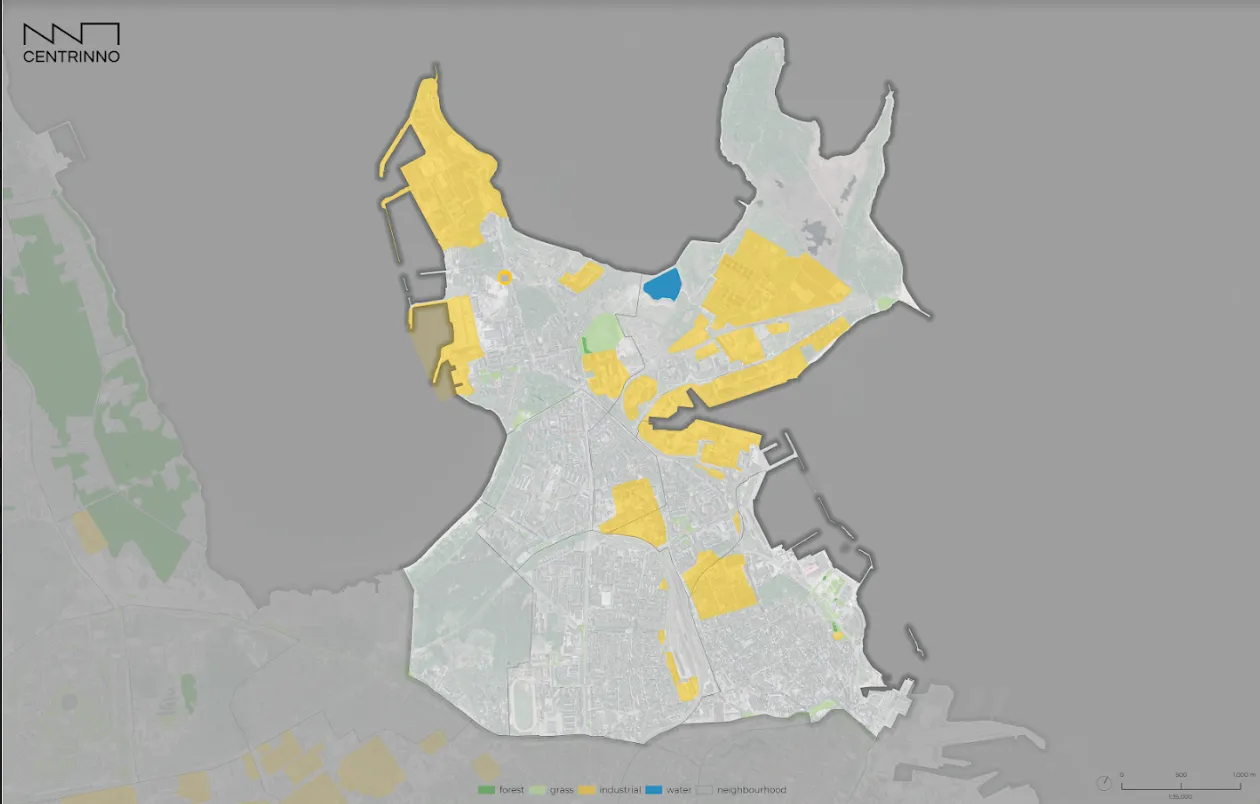

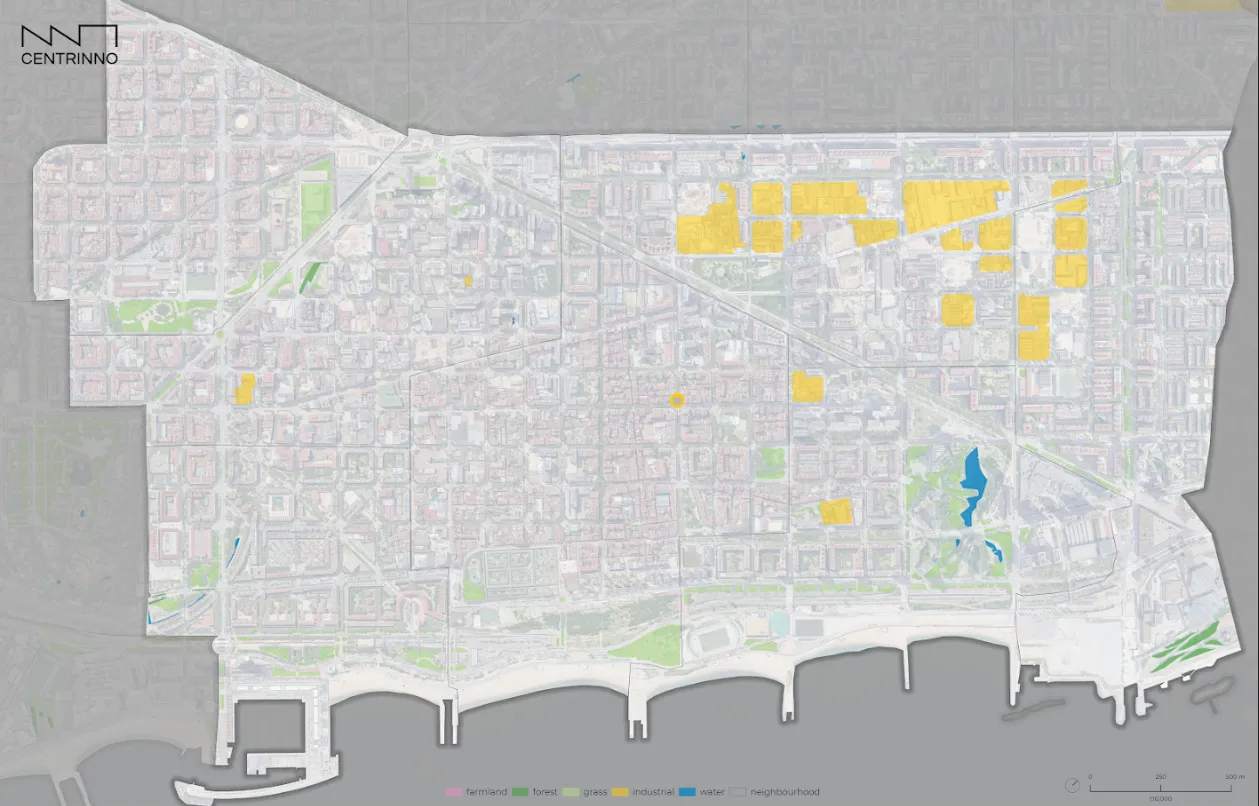

Erki explains that, when the hives are open, the bees travel up to 2 KM in any one direction, meaning they cover a total area of 12KM². The bees’ pollinating activities thereby connect them with the rich flora that calls Tallinn home, which is itself the product of a curious historical trajectory inextricably tied to the industrial activities undertaken in the port in previous centuries. Another local beekeeper, Roland Pollu (who has the titular role in the Living Archive story Roland the Beekeeper), who has been another fixture in the beekeeping community since taking over his grandfather’s hives several years ago, has observed this first-hand. According to Pollu, prior to the industrial port’s operations, the area of Kopli was sparsely populated, closer to a fishing village than a thriving urban centre. Because of this, even the workers’ lodgings that sprung up to support industrial work were something of an outlier: there remained plenty of space for greenery to flourish. Many houses had or still have gardens.

Beekeeper Roland Pollu. Photo credit: Elo Strauss via CENTRINNO Living Archive

Due to the sudden boom in international, globalised trade in the first half of the 20th century, many different natural entities – plants, fruits, vegetables, fauna – began passing through the port. These gardens’ proximity meant that different species of plants, including many non-native to the area, became part of the local ecology. The array of natural imports from distant countries via industrial activity meant that the biodiversity of the Kopli area flourished, giving the area some of the ‘weirdest varieties’ of ecosystemic features, such as the location’s unique berry bushes. The area’s relative historical deprivation plays a role here too, being – in parts for ‘hundreds of years’ – neglected to the point of becoming overgrown, which again has underpinned the cultivation of the unique and healthy local flora. As a result, says Pollu, the bees pollinating the local ecology come to enjoy something of a ‘gourmet lifestyle’, benefitting from the richness and and the depth of Kopli’s flora, which in turn encourages the bees in their pollination efforts.[4]

Intertwined ecological and industrial pasts

In this way, we see through bees how the natural history of plants and wildlife in the area is inextricably tied to the history of industrial activity in the port – or the lack of it when industrial work began to slow. Such a separation should urge us to think more critically about the notion of human and non-human lives being wholly separate entities. It should also encourage us to think differently – as is often returned to in the CENTRINNO project – about what heritage is and how it can be understood. Can, for example, the ecosystem be understood as a kind of heritage? What is this flourishing ecosystem process, if not a direct link between the past and the present?

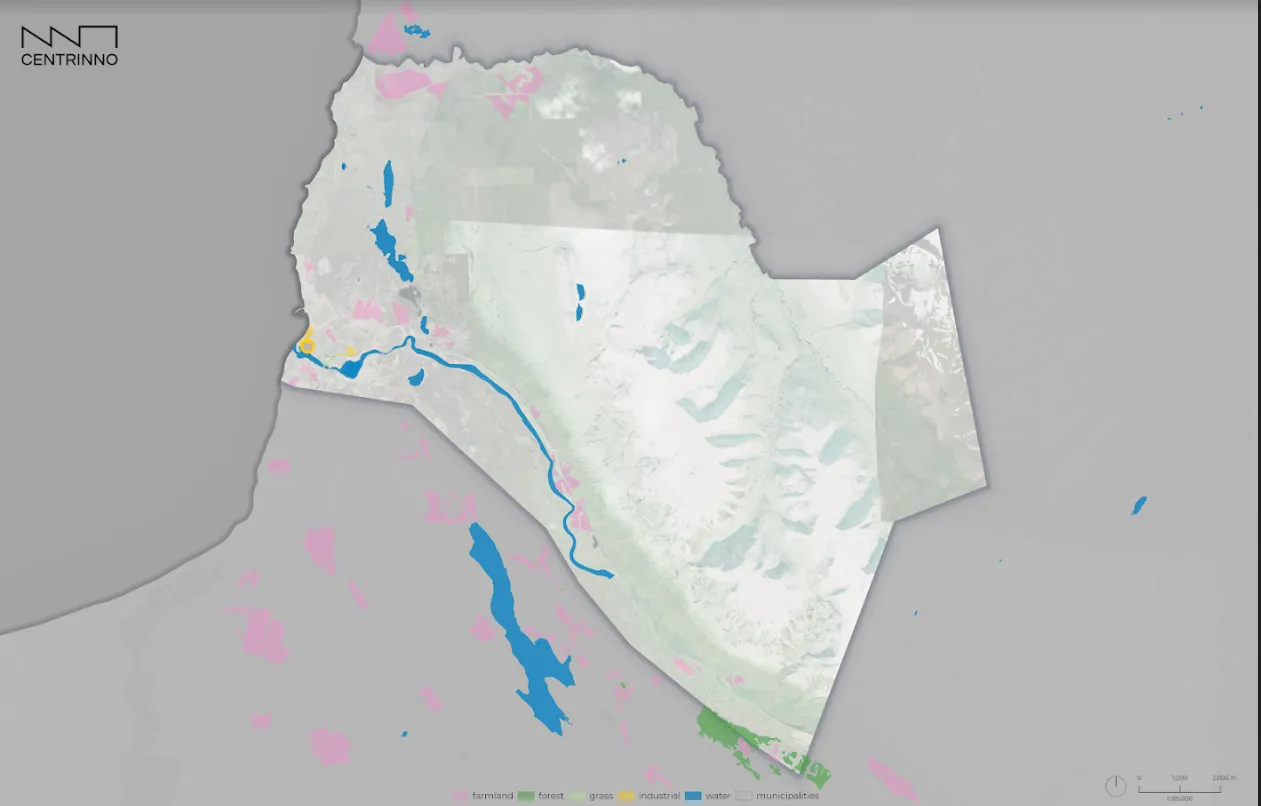

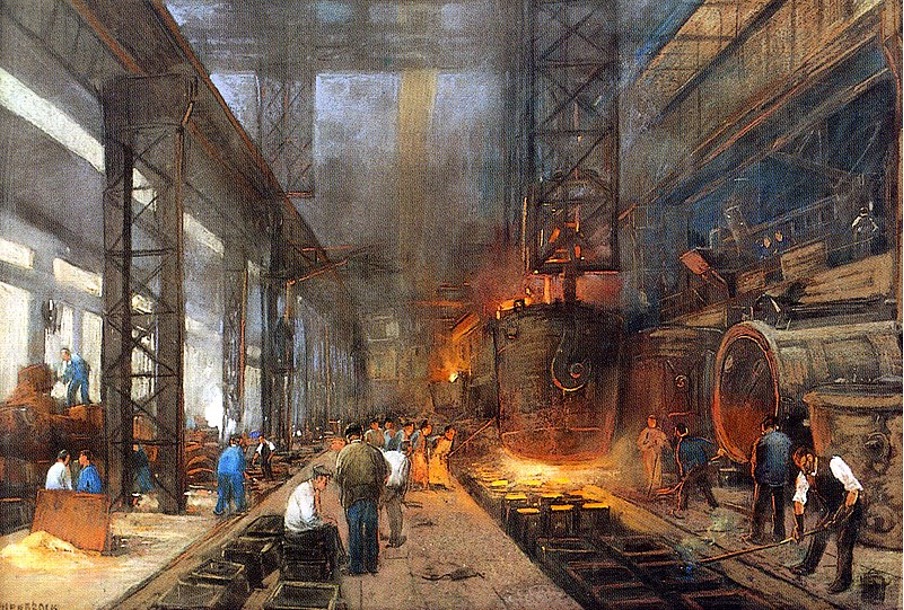

Unfortunately, this broadened way of understanding the heritage of the industrial era, including the ecosystem that developed in its wake, is not only linked to a positive coupling of human and non-human life. The flipside of this historical relationship between industry and local ecology is found in the archetypal negative side-effect of industrial-scale manufacturing: pollution. Just as bees carry with them the benefits of a globalised biodiversity, so too does their pollen carry traces of the chemical effluents that have long circulated through and been combusted around the port in Kopli and other areas of Tallinn that are more heavily industrialised. As a result, Erki describes, their pollen has been found to contain traces of the likes of Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (commonly known as DDT), a ‘chemical that kills everything’, as well as heavy metals such as Zinc, having been oozing through the soil for decades. While the samples of pollen collected from the Kopli bees was found to be some of the cleanest from the samples collected from bees all around Tallinn – likely because of the aforementioned local biodiversity – there remained some traces of these pollutants. That there are legacies of industry seeping into the pollinators around the city is again an incentive to revisit the idea of heritage. Bees remind us that so-called ‘toxic heritage’ is part of the construction of modernity, particularly in places characterised by an industrial hub, and may be carried by subjects less-associated with industrial history than the cavernous warehouses and sublimating machinery of the era.

Empathy and the capacity for change

To move beyond the climate-blind perspective definitively characterising the last centuries of western- or Euro-centric human history may require a new perspective entirely removed from the human-centred and profit-oriented logics of the industrial era. After all, it is not as if there is an absence of data on climate change’s imminent effects. There is however a dissonance between this knowledge and the capacity or will to act on it. The reasons for this are manifold, complicated, and often, seemingly insurmountable. As Anne-May Nagel – also from Tallinn’s pilot team – tells us, one of the key things for changing people’s perspectives might be the grounding effects of a truly and deeply experienced empathy. Empathy, argues Anne-May, is more effective than press releases, or data visualisations, (or indeed blog posts like this) at bringing people into contact with the effects of climate change, and creating the conditions by which people feel the urge to act upon it. It is ‘one of the only things that really works’. [4] Perhaps this is because of the distance between the immediacy of day-to-day human life, and the long-term, abstracted effects of a changing climate happening on both global and micro-scales.

Cultivating and caring for bees not only generates empathy, but also reduces this distance between human and non-human life. At a certain point, this could be understood as an act of humility, a way of ‘humbling people’, consigning ideas like that of the human-centred prioritisation of profit over the flourishing of life at large to the scrapheap. When engaging in an activity such as beekeeping, and observing the need for conditions by which they flourish, it is difficult to maintain this idea of human superiority over nature. As Karin argues, ‘when you start interacting with nature with such intensity. It’s not just about a trip to a forest, it becomes your lifestyle.’ [4]

Photo credit: Elika Klettenberg via Eesti Mesinike Liit

New lifestyles, new possibilities

Certainly, new lifestyles are necessary and urgent to address the climate issues that press onto our present in very real and immediate ways. This is not news to people who keep bees, whose attunement to the conditions required for ecological subsistence means that the supposedly unpredictable weather events that decimate ecosystems have become distressingly predictable. Such climatological instability is not random, but the long-foreseen result of a history of using fossil fuels to drive the construction of modernity. [5] Speaking to the fullness of this history, and using a heritage methodology to investigate how material and ecological entities are differently woven into it, is part of the CENTRINNO approach to cultivating futures otherwise. In Tallinn, this has meant incorporating beekeeping days alongside such CENTRINNO activities as heritage days, meaning that visiting children not only learn about the shipyard, and the sustainable operations being undertaken today, but also about bees, as these separate entities cannot be considered unconnected to each other. Understanding that bees and ecology have been part of our (post-)industrial trajectory for decades makes them part of what Donna Haraway calls the ‘fabric of this undoing’, as the old ways in which history clings onto the present fall away, and begin to decompose. [6] In the mulch of what is left behind, there might be the possibility of something new, ready to be pollinated by bees like those in Kopli 93.