BLOG

Promoting local and circular manufacturing in urban contexts: the case of Manifattura Milano

In recent years, the city of Milan has undergone numerous transformations in order to try to mitigate the challenges of the world’s great metropolises: population growth and consequent social exacerbation, an increase in urban waste production, the climate crisis, and recently also an acceleration of the energy and other supply crisis.

These well-known challenges have led to reflection on the role of the city, rethinking its spaces and services, and seeking solutions and tools to mitigate these threats.

Successful examples of these attempts have been in Milan the use of calls for tenders by the public administration to support micro-small businesses or projects that are particularly attentive to the social aspect and the territorial dimension, seeking a transversal collaboration between the public and private sectors aimed at caring for the city1.

More generally, the attempt – followed internationally by other cities – to implement a city model in which essential and non-essential services can be reached quickly, creating those economies of proximity useful for striving towards the so-called 15-Minute City2.

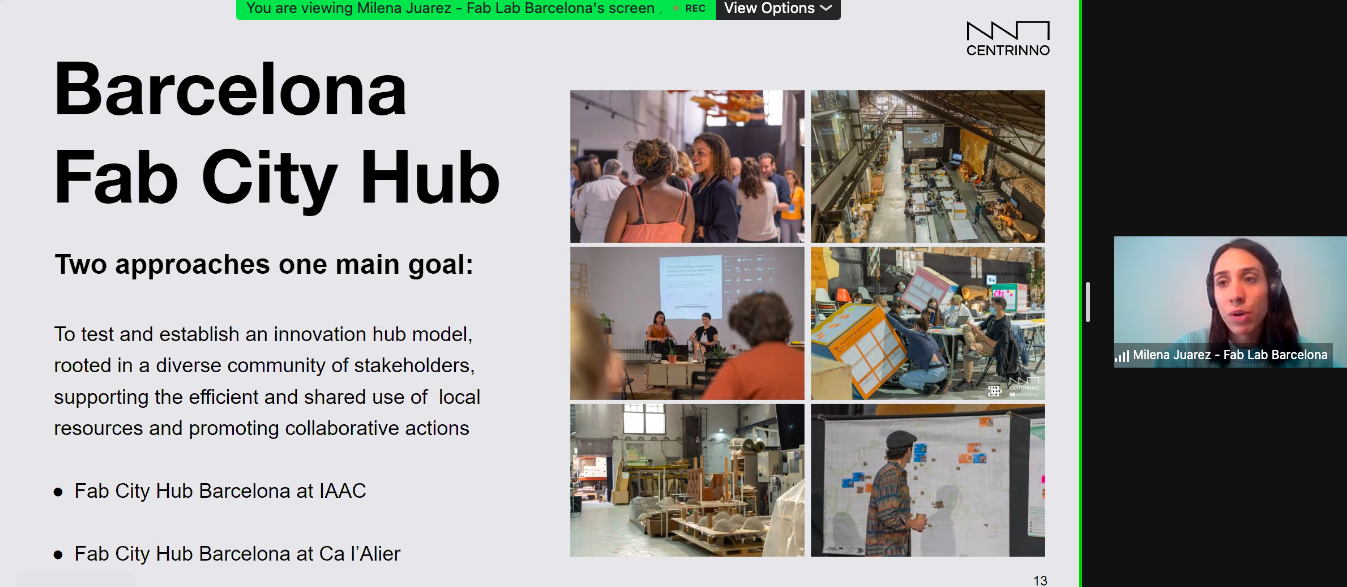

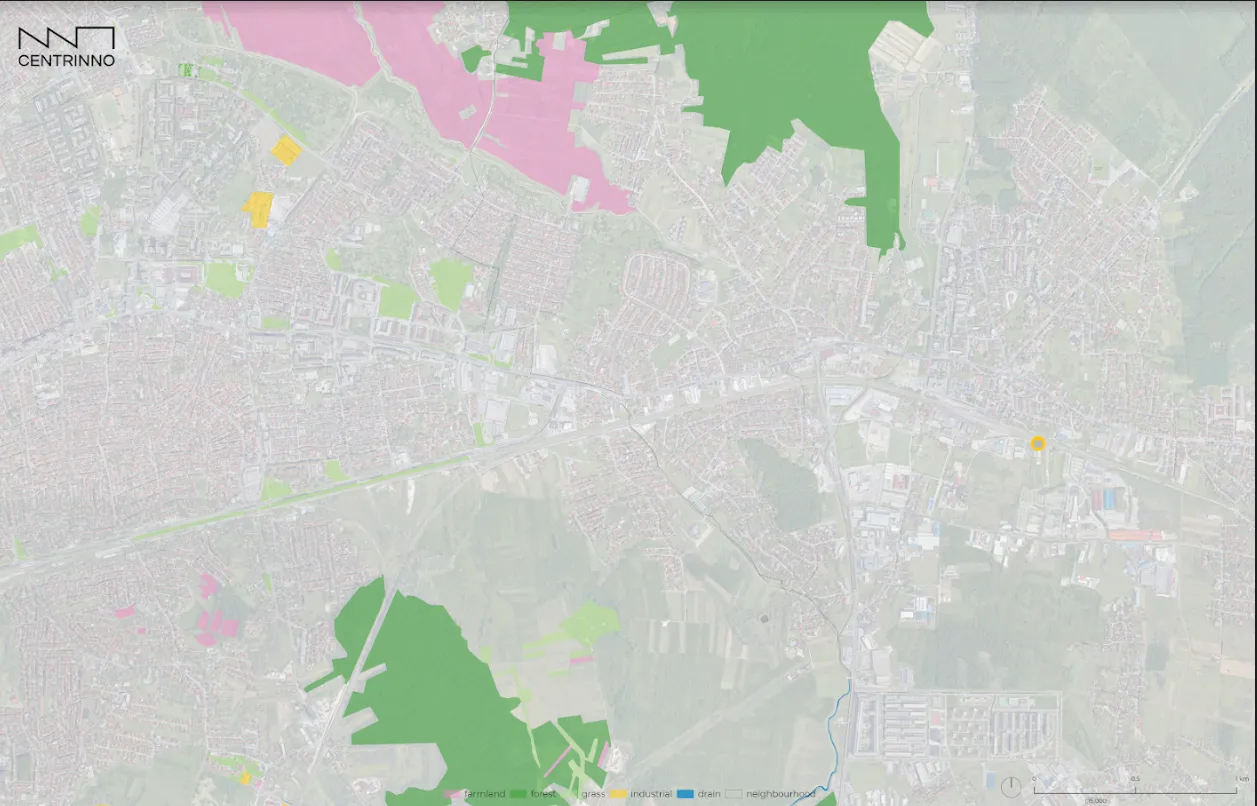

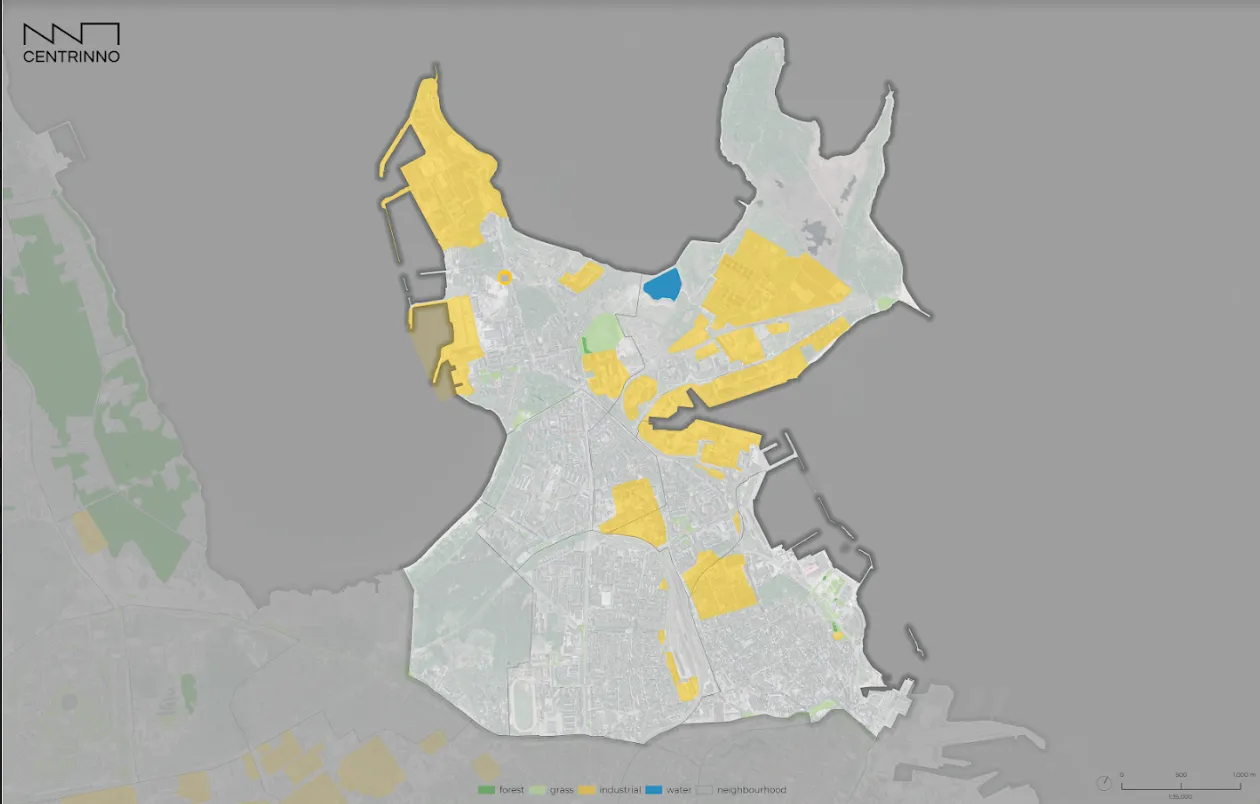

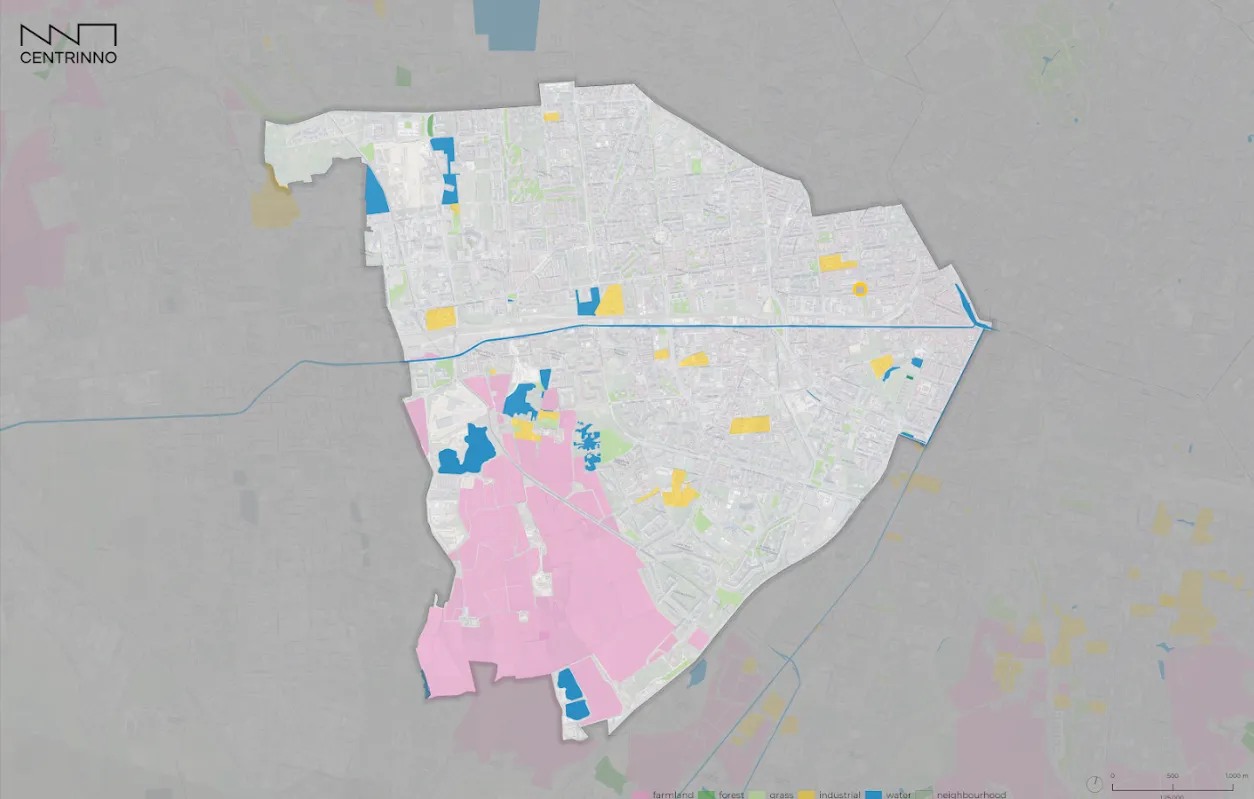

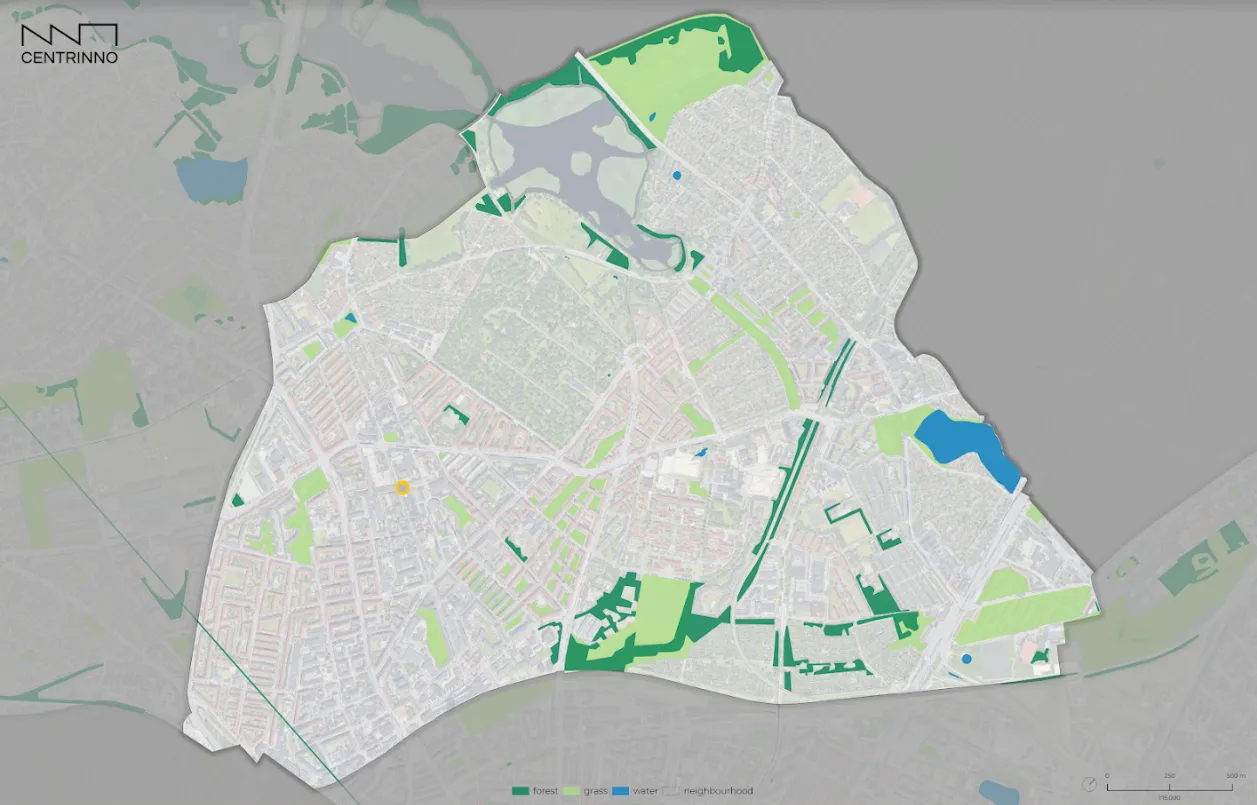

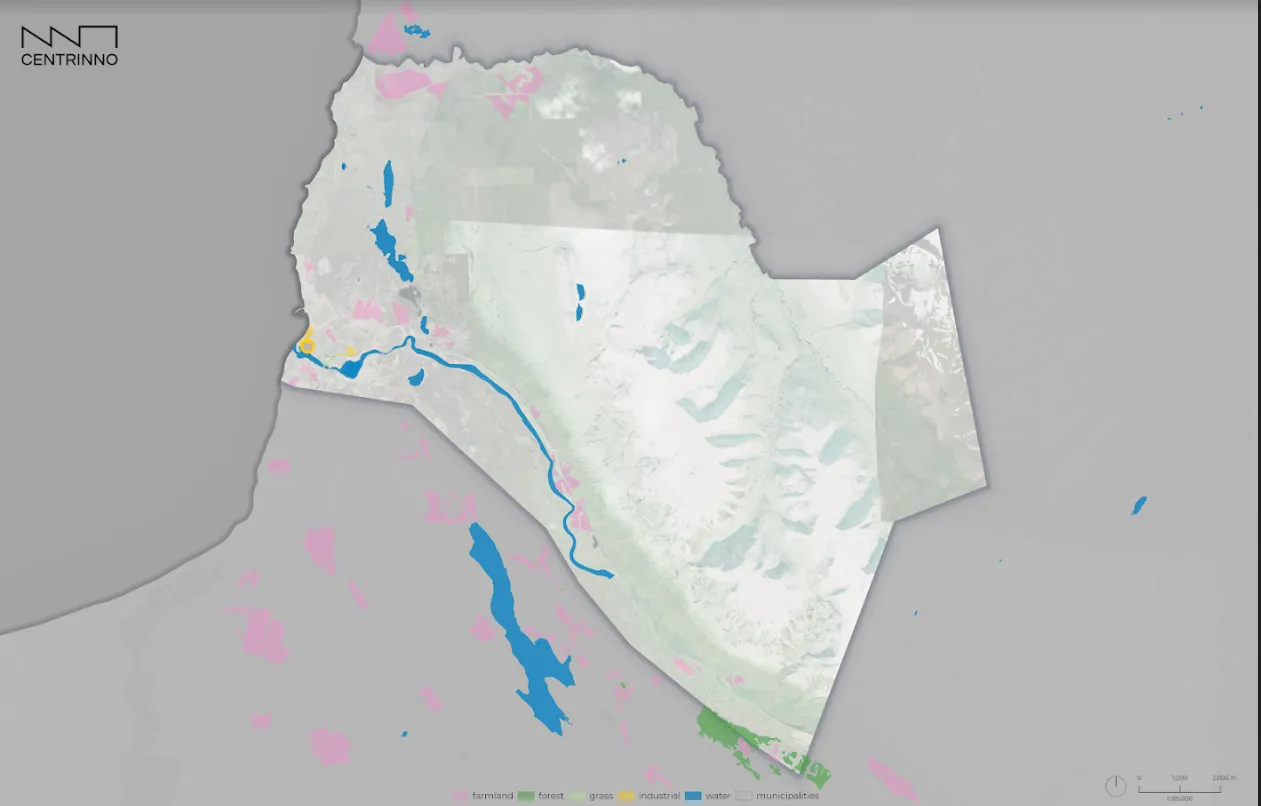

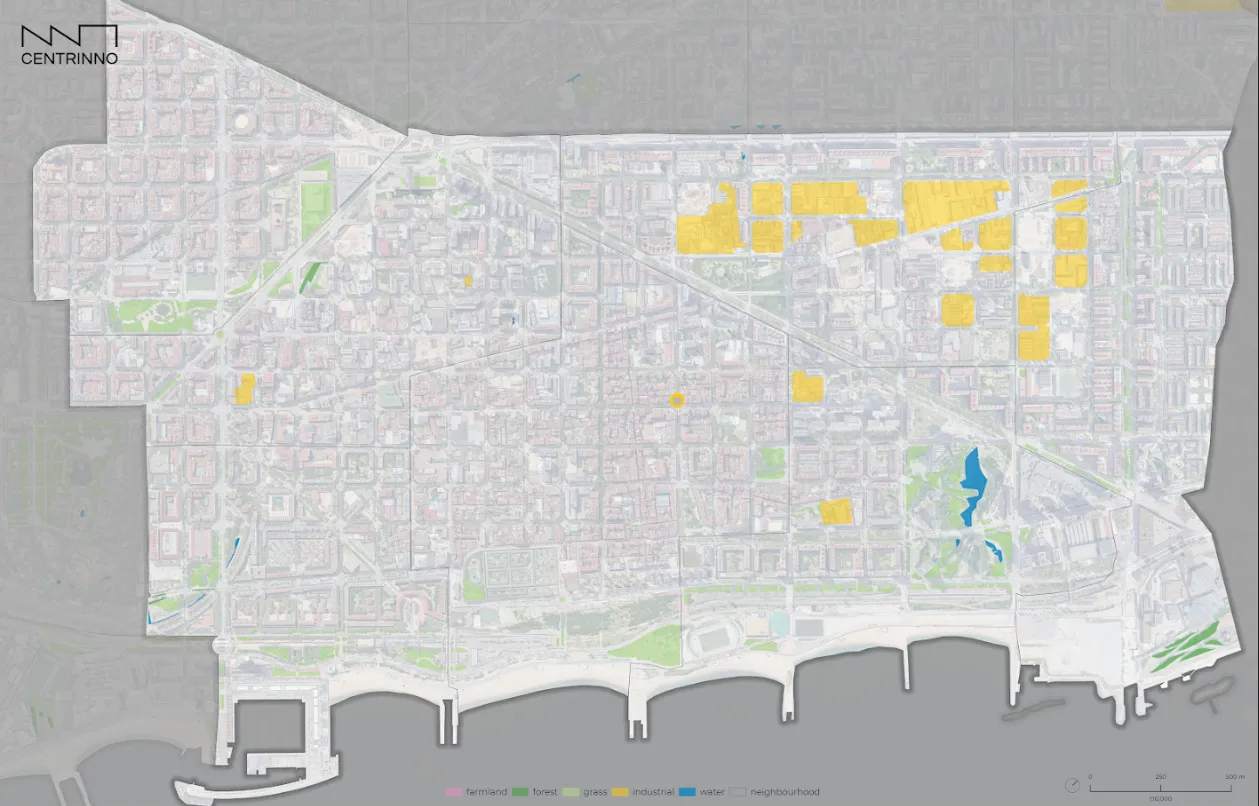

In this framework, the European project Centrinno through its Milanese pilot has from the outset sought to imagine how to deepen and analyse the productive dimension of the city. In other words, to understand how it is possible to implement the vision of a self-sufficient city in terms of goods and services – following the Fab City3 approach – and the need to rethink spaces – neighbourhoods – in terms of proximity and accessibility.

The starting point, integrating these two opportunities

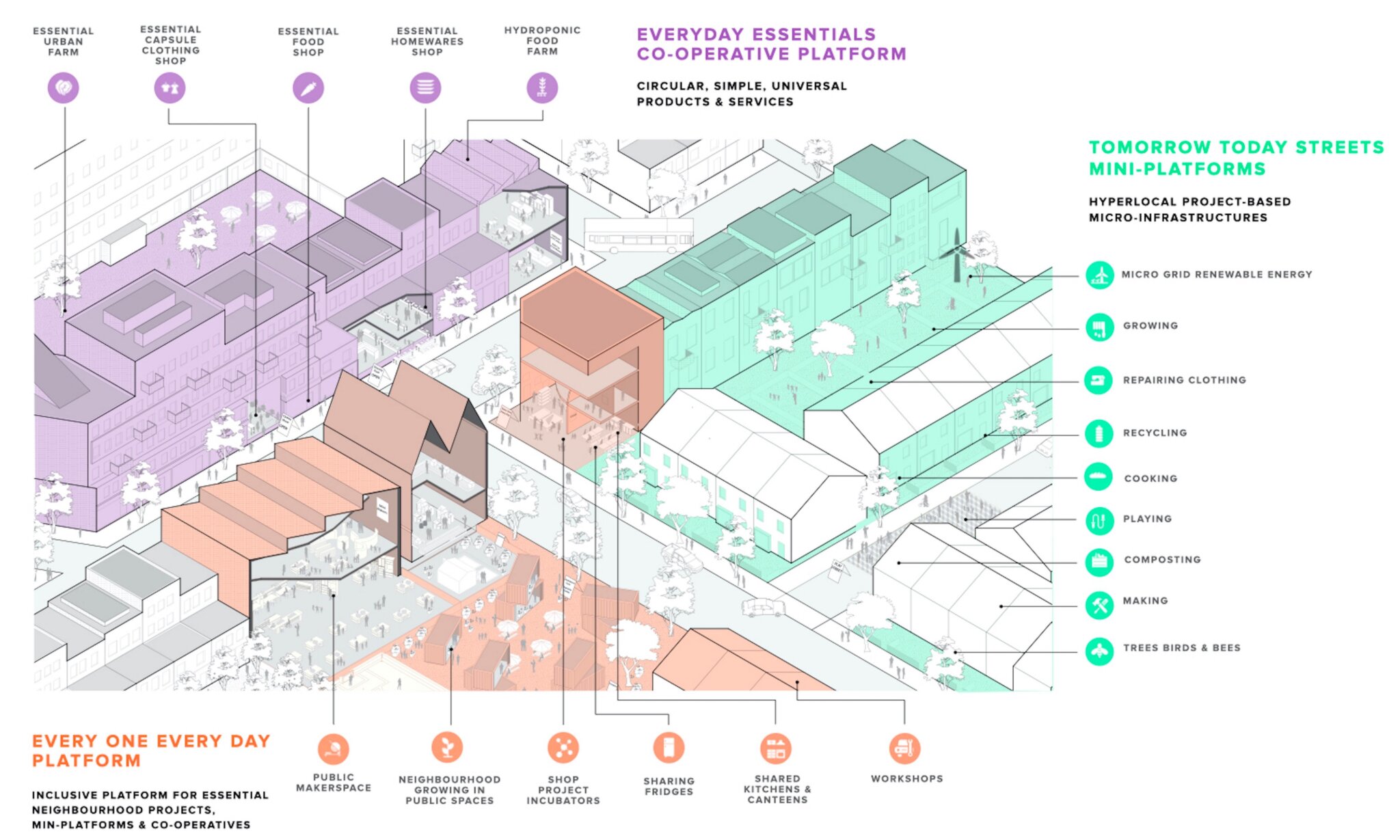

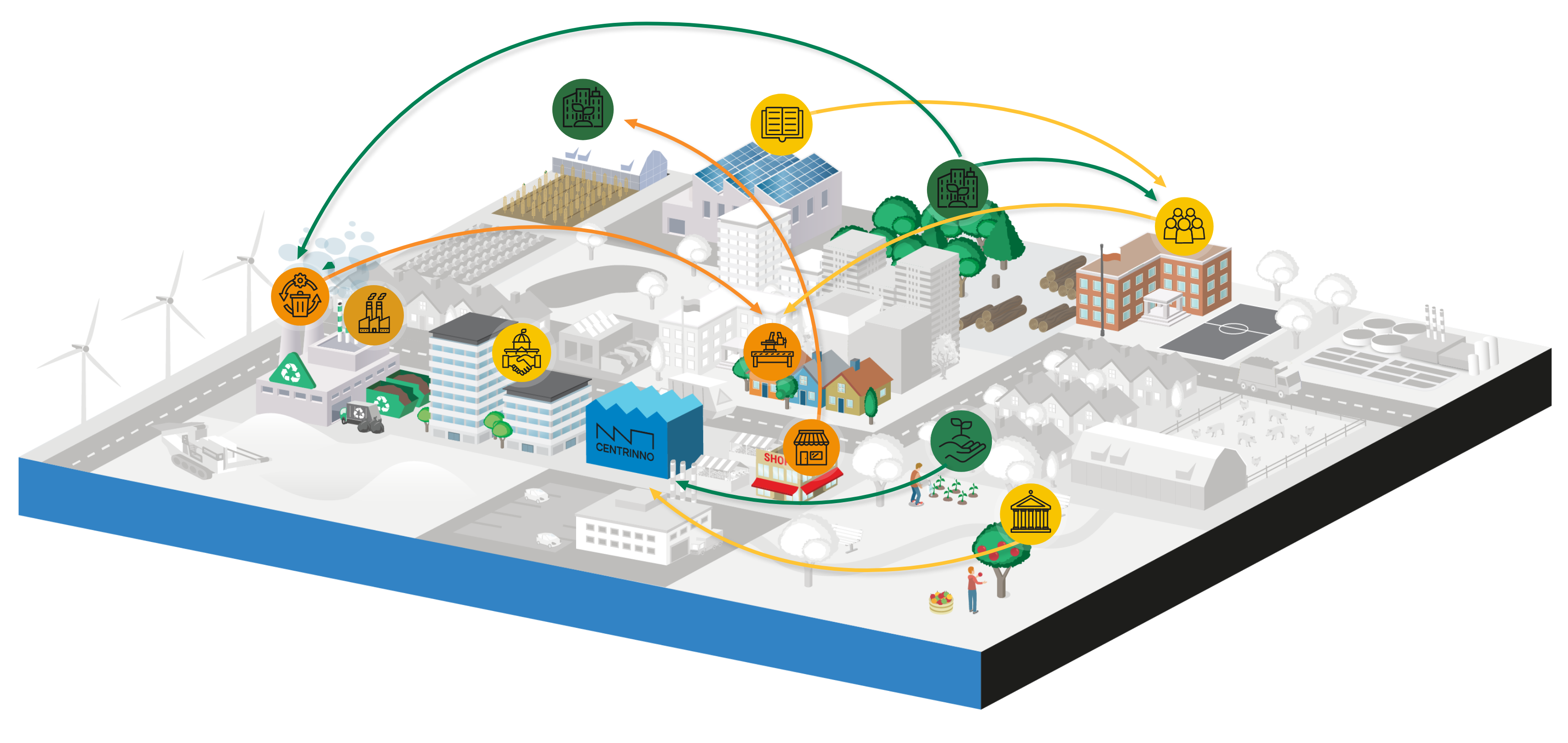

The Fab City concept and its productive dimension fits perfectly with the goals of the 15-Minute City. By promoting local production and encouraging self-sufficiency, it contributes to the creation of resilient neighbourhoods where inhabitants can access goods and services, the 15-Minute City circumscribes the spatial element: the short distance from home.

Combined, these approaches can facilitate the reduction of traffic, carbon emissions and the overall environmental footprint of cities, while nurturing local urban production – hopefully also mindful of the principles of circularity, which have now become an international standard.

This was one of the initial aspects of the Milanese pilot.

How can the Fab City concept be applied in Milan? Does it make sense to speak of individual Fab City Hubs – the places of digital and non-digital production that facilitate the formation of these ‘metropolitan autarchies’ – or can there be other forms of local production? How can these two theories be integrated? What role do public administration and the policies derived from it play in this context in the Milanese context? How can a return to local production be promoted in an international city? And finally, how can production on a neighbourhood scale be protected?

After four years of the project followed by listening phases, meetings, events, training courses and institutional confrontations, we can say that for Milan a direction to move towards is a collaborative approach that involves and creates partnerships between the public and urban manufacturing networks capable of generating public strategies designed to be dynamic instruments of change.

The collaborative approach

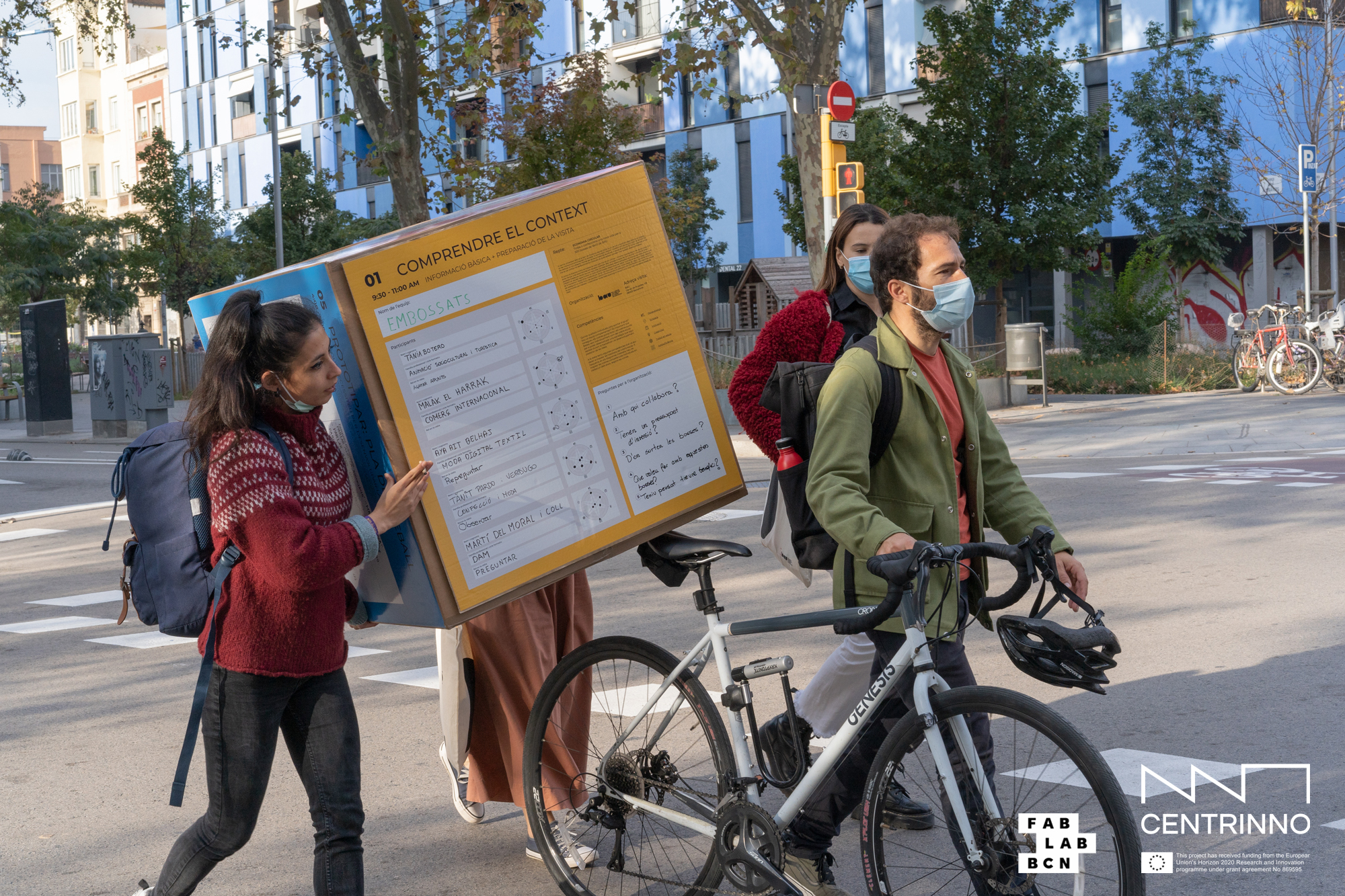

During the project, we chose to envision this transition to self-sufficient and sustainable cities and neighbourhoods through a collaborative approach that would involve all the actors involved in such a change.

To do this, we focused on three key activities: Community, Open call and Co-design.

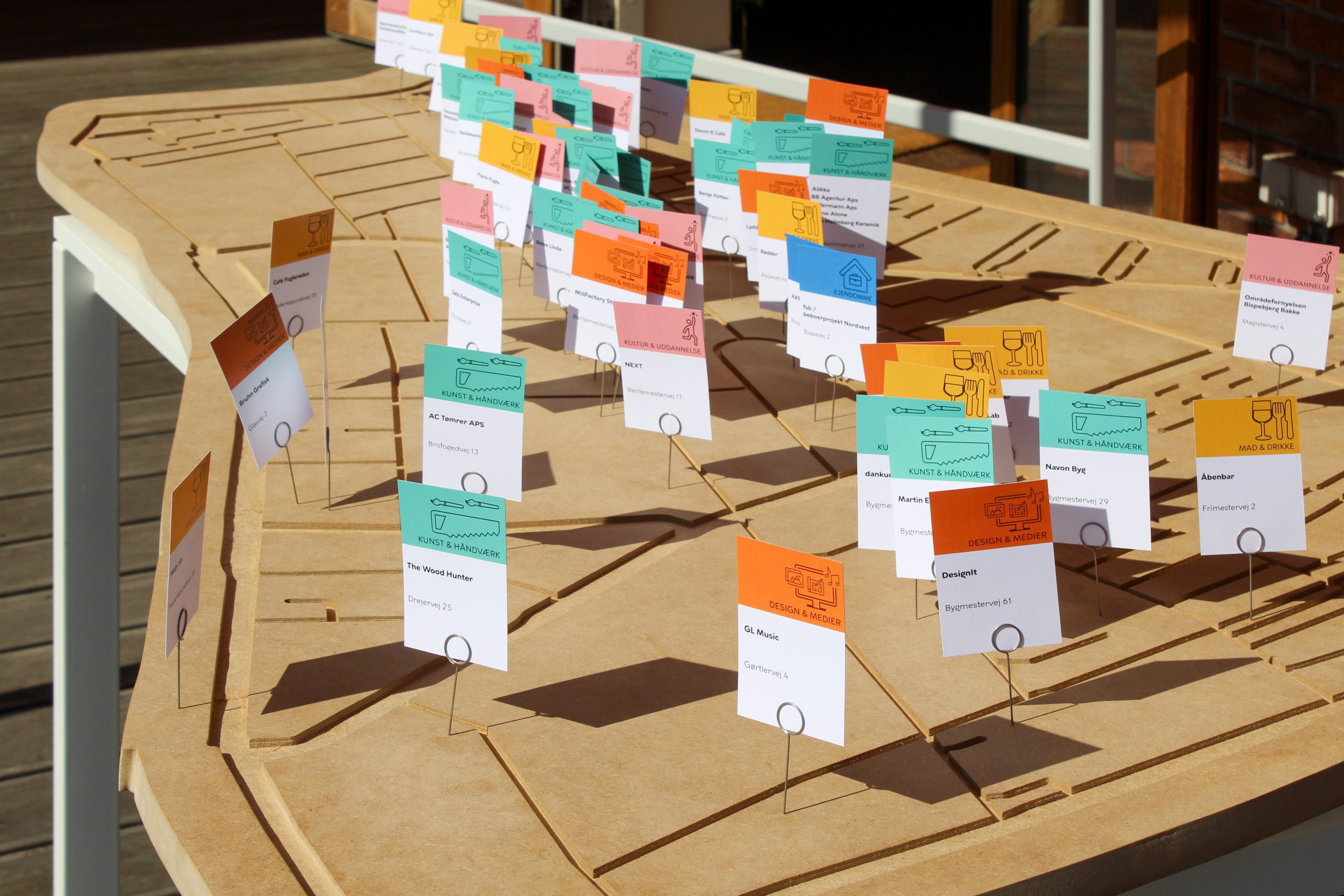

- Manifattura Milano’s community building has gone beyond mere cliché and become the heart of our collaborative approach. Stakeholders are not merely passive recipients of policies, but active participants in a collective journey towards circular production. The proactive involvement of these stakeholders – and opportunities – has cultivated a sense of belonging and commitment. More than 120 Milanese production businesses recognised themselves in shared values and through dialogue highlighted critical issues and possible solutions for a local Milan in terms of production and circularity. Another fundamental aspect linked to the constitution of a community was the possibility of mapping all those products born from collaborative and reuse and recovery approaches typical of the circular economy4.

- Open Call: these ‘open calls’ were useful and indispensable tools for the creation and maintenance of the community and acted as a first building block for the formulation of shared public strategies. One of the most successful examples in the four years of the project was undoubtedly the case of Milano Circolare5: a two-day event on aspects of circularity in textiles and design created for the most part by proposals and responses to an open call laying the foundations for the formulation of public strategies reflecting collective needs and aspirations.

- Co-Design: While open calls were the first building block, co-design activity is certainly at the heart of our public strategy formulation method. This approach brought together stakeholders from various areas to collectively shape proposals to guide the city towards circular production. Through workshops, trainings and dialogues, it has been realised.

The most important result of this collaborative approach is undoubtedly the birth of Milan’s circular economy plan for the fashion and design sectors.

A dynamic policy document that incorporates the needs of stakeholders in the area and envisages their active involvement in its implementation. A first step towards a collaboration between public administration and the private sector with the aim of creating a dynamic ecosystem in which local circular enterprises can thrive, contributing to the city’s sustainability and resilience.

Looking forward

In conclusion, imagining a future in which Milan embraces the 15 Minute City and the Fab City concept is possible and feasible and would not only redefine the city’s environmental sustainability, but also redefine its identity.

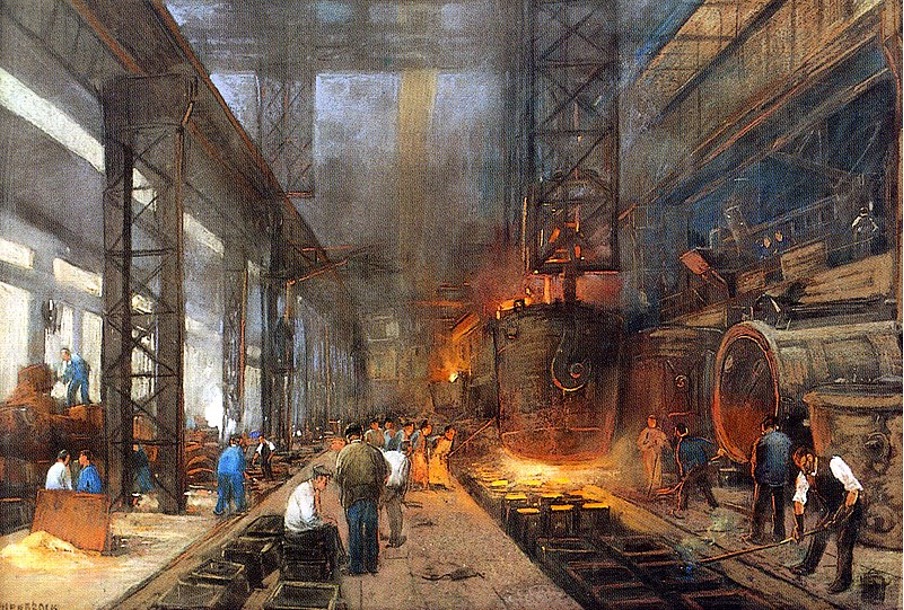

Integrating local and circular production practices into Milan’s future urban planning aligns with its rich tradition as an industrial centre, becoming a source of inspiration and innovation and transforming factories and industrial spaces into centres for sustainable production.

This future-oriented vision not only preserves Milan’s cultural heritage, but makes it a model of sustainable urban development capable of celebrating its history while embracing a circular and ecological future.

While the possibility of integrating these two opportunities seems feasible and, in our opinion, should start from a shared involvement of the territory’s actors, the tool of a single place deputed to production – the so-called Fab City Hub – represents, for Milan, a model that is not fully applicable, but can be replaced with a more widespread approach in which production realities within the urban space, collaborate with the public.

A final aspect in order to make cities – characterised by small-scale production – truly self-sufficient, and on which synergetic intervention at the international level is needed, is to find the right balance and the appropriate regulatory tools to be able to experiment with material and waste flows at the urban level.