BLOG

How to gather a consistent alternative food system in Paris

How to gather a consistent alternative food system in Paris

How to gather a consistent alternative food system in Paris

Reflections two years after the beginning of the CENTRINNO European Program

abstract:

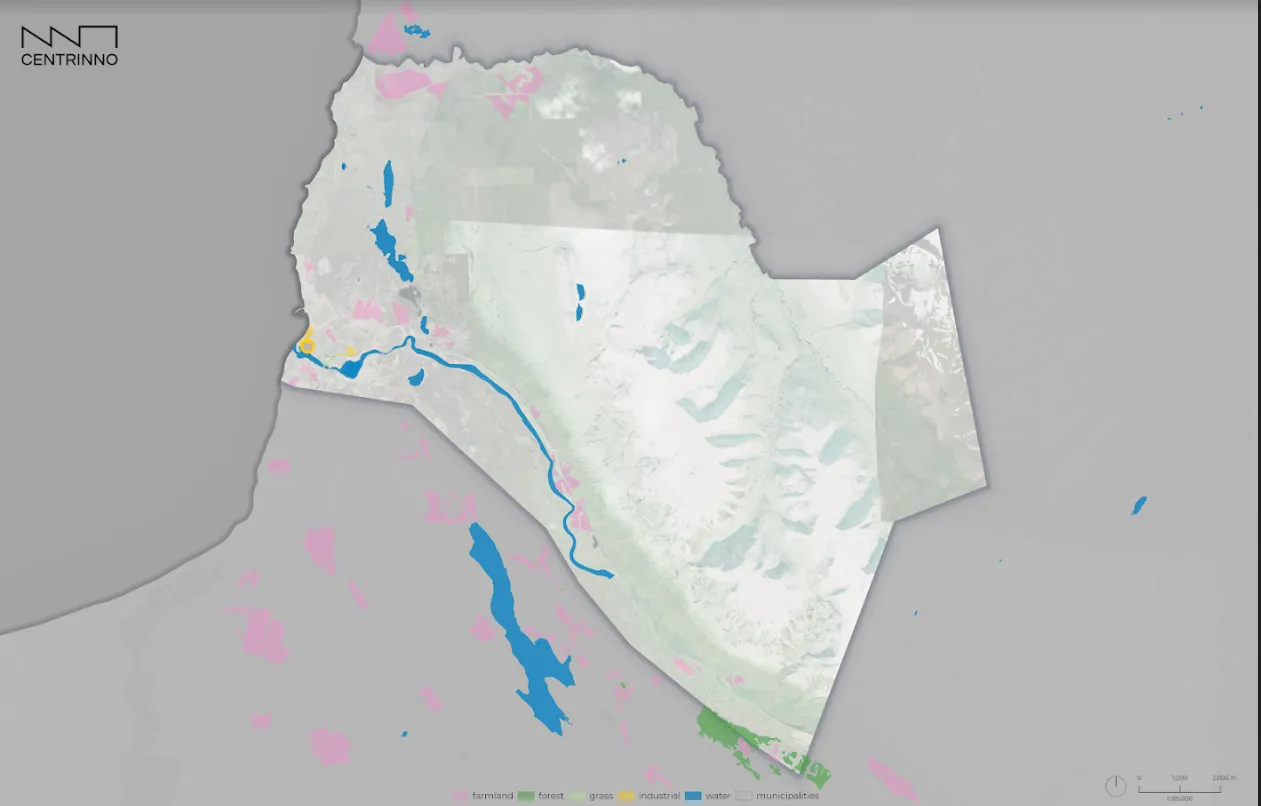

The CENTRINNO program began in November 2020 and among the 9 Pilot cities working on various topics all linked to the rehabilitation of industrial historical wastelands, Paris chose to focus on the urban food system and how to propose an alternative to the actual globalised agriculture which condemns cities to no longer have visual access to what they eat. In this blogpost we explore how our Pilot has grown and changed during the first 2 years of the project, considering the vivacity and the diversity of the alternative food system actors and the various dynamics underneath.

- The Parisian context : too Big to change ?

Paris has a double DNA concerning its food system and more generally its productive dynamics intra muros, which can either oppose or combine to generate new alternatives.

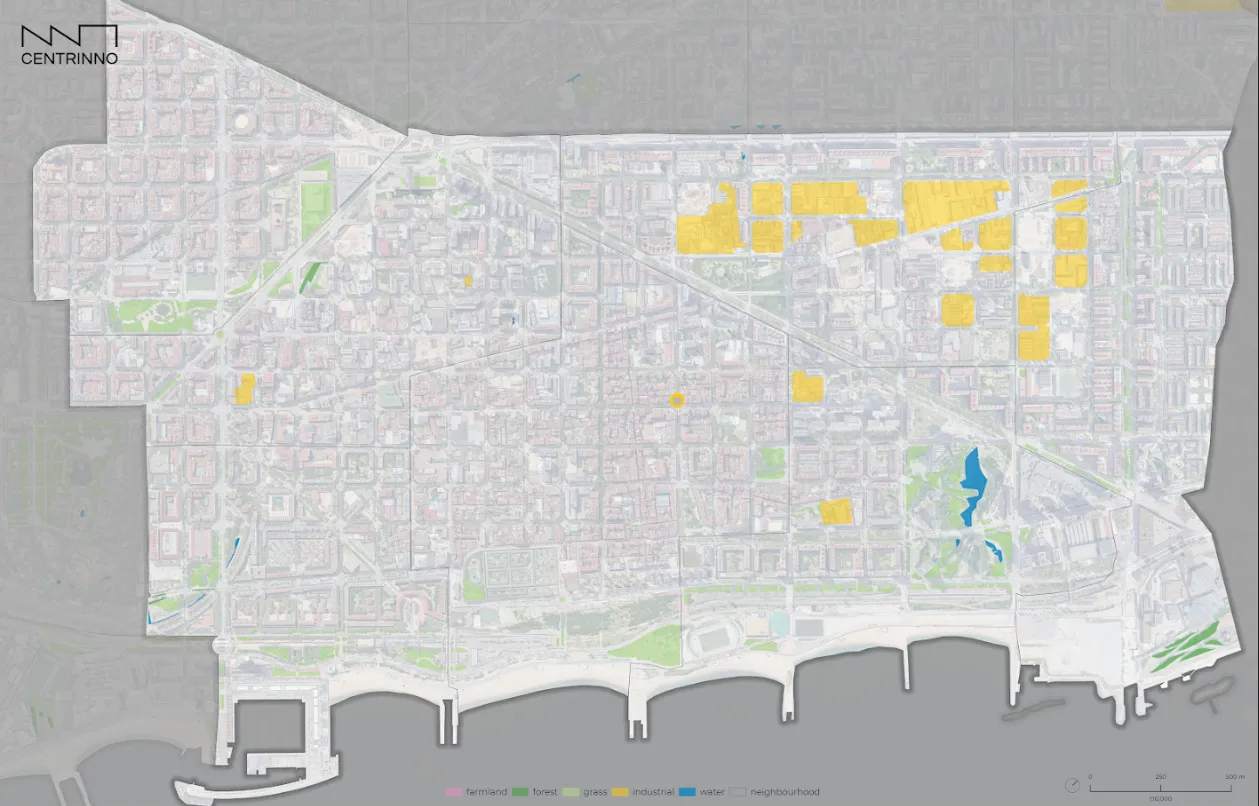

On one side Paris is the most dense city in Europe with more than 21,000 inhabitants per km2 and one of the most expensive real-estate cities in the world. These factors create a strong pressure on low-income populations and on small companies, in particular on businesses active in small-scale production and craftsmanship which includes independent food players.

Production activities keep being pushed out of the city. Even more, rampant artificialisation is blocking access to edible urban nature. Parisians lose sight of their food and thus lose the meaning of their diet. It is therefore not surprising in this context that the majority of the inhabitants undergo a food dependence on the products of the large distribution preventing them even from realising the abundance of small local initiatives around them.

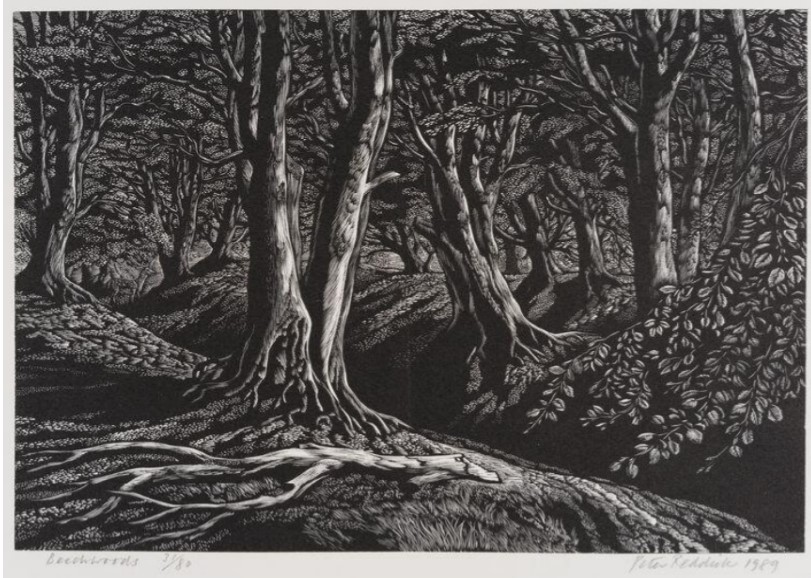

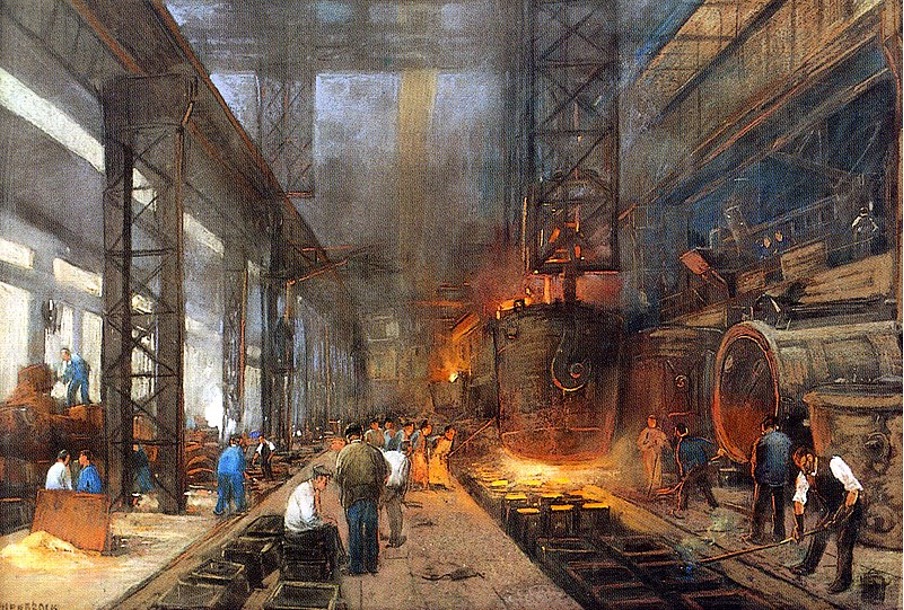

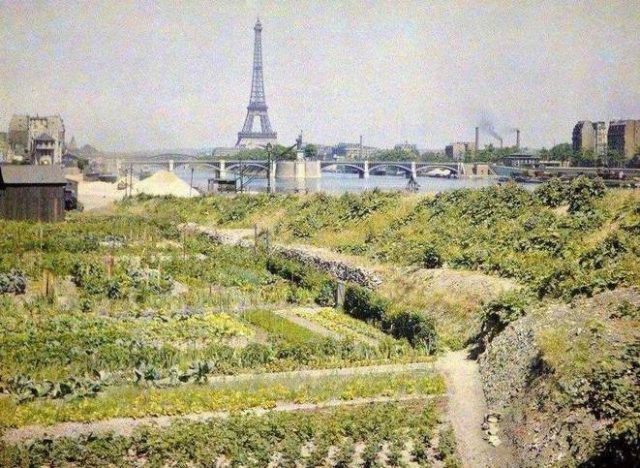

On the other side If we look back to history, there is an interesting exception though. During the period of 1870-1930, Paris and immediate suburbs developed a type of market farm that was unique in Europe and that still inspires today. Remote farmers that were attracted to Paris in search for work established an ecosystem of farms on small pieces of land interstitched in the urban tissue. On unfertile land they managed to obtain unrivalled productivity through the introduction of new farming techniques & tools and through recycling the city’s waste.

Allotment gardens in Paris around 1870 Jardins potagers, quai d’Auteuil (actuel quai Louis Blériot) en face le pont de Grenelle et la statue de la Liberté / © Musée Albert-Kahn

Today, apart from this historical background and France tradition of gastronomy and food rituals, Paris is also hosting nowadays an incredibly line-up of start-ups, NGOs and initiatives related to food and urban agriculture including: roof gardens, old rail stations converted into urban farms, underground farms, foodlabs, micro-cheese factories, microbreweries and so on. Some of these initiatives are the fruit of a larger strategy led by the City Council for sustainable food and urban and peri-urban agriculture.

The initial aim of the CENTRINNO Paris pilot was to give spaces and to connect these initiatives at a neighbourhood level to propose a consistent alternative to the actual urban food system.

2. How to handle a 12 millions people challenge ?

- Two sites in a a symbolic district

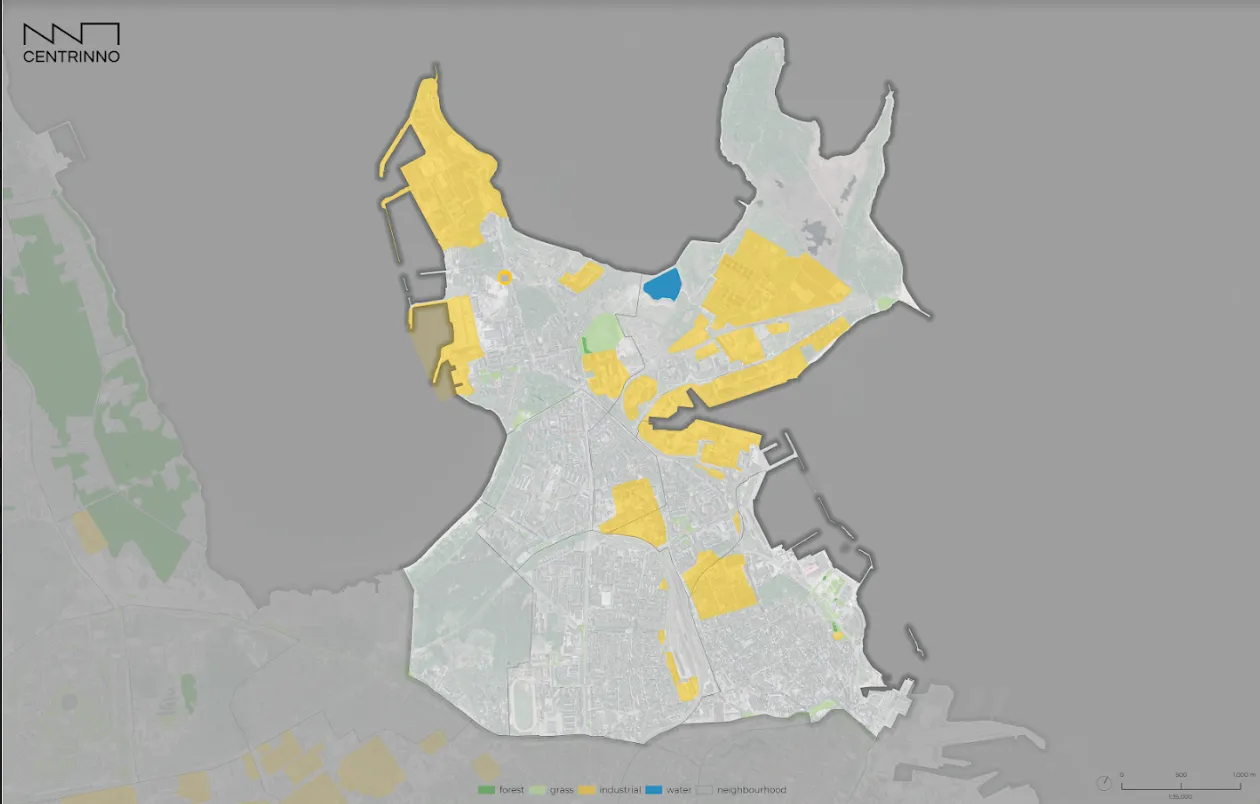

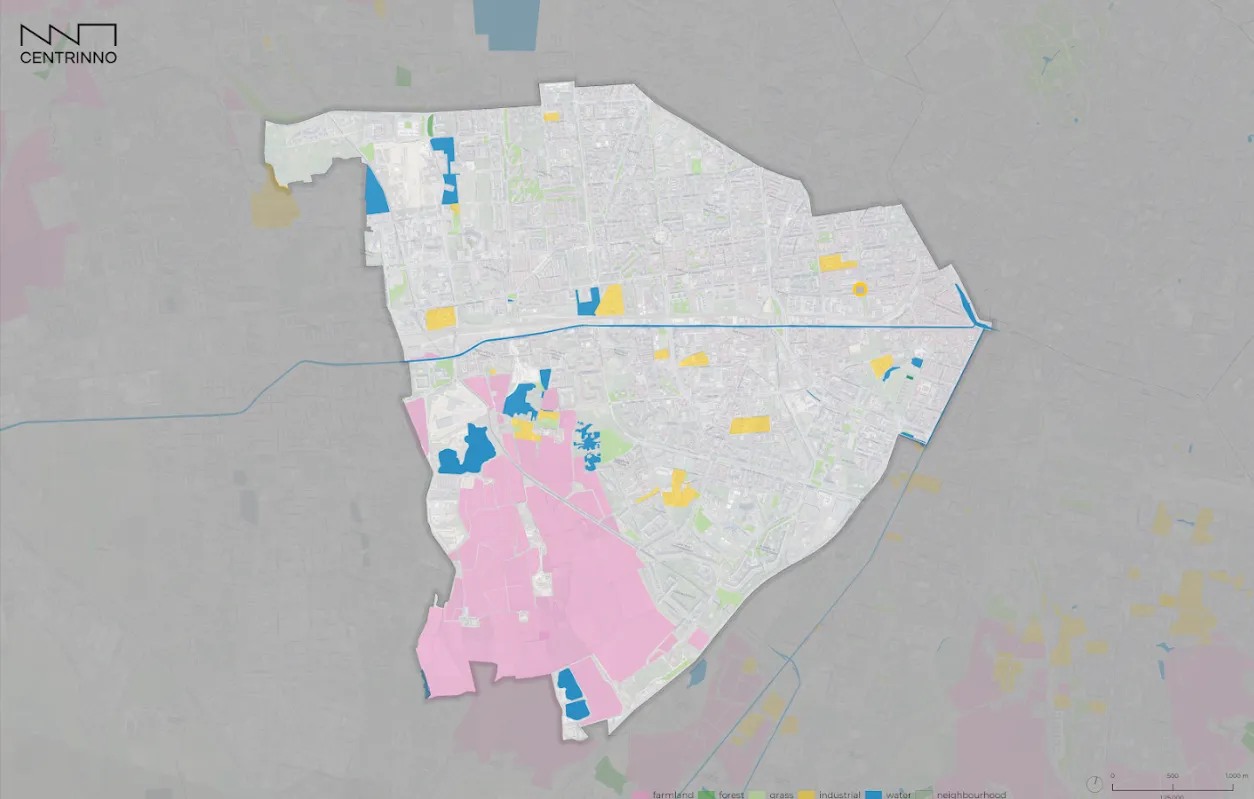

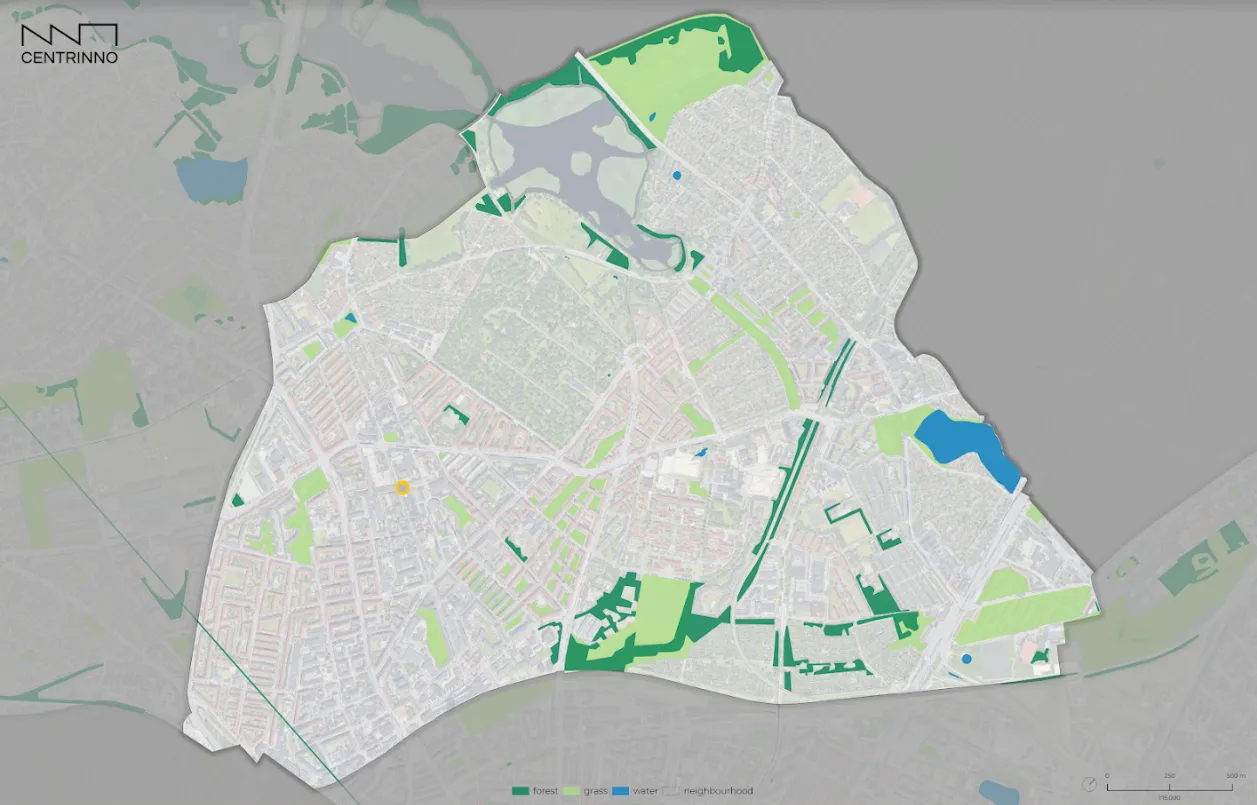

Initially, the pilot focused on implementing the CENTRINNO framework on two ongoing sites in the north-east of the city (one of the poorest areas and with the strongest industrial heritage). These two experimental sites are drawing a way for the future of sustainable food scene in Paris in terms of economic, social and cultural impact.

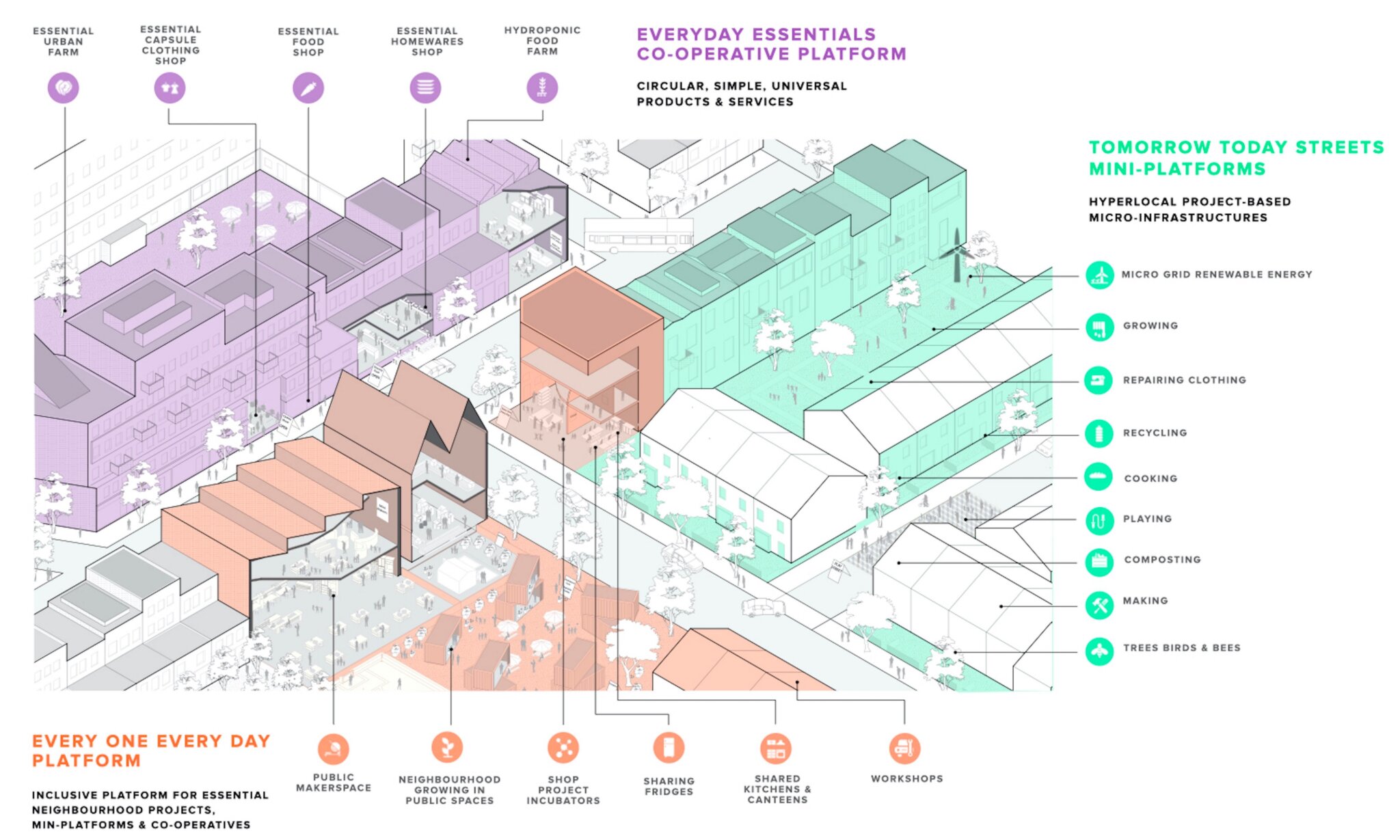

The first is the FabCity Hub Paris in the north east of the city, a real estate operation run by the City Council and Oasis21, a land cooperative focused on social economy. The Fabcity Hub Paris aims to be a creative and productive hub including a co-working space, a foodlab and a makerspace. The second site, is le Jardin des Traverses, a project run by Vergers Urbains which plans to convert a former railway path into a walkable urban garden to experiment new paths for food production, food transformation and distribution, education and social inclusion.

- A complementary collective

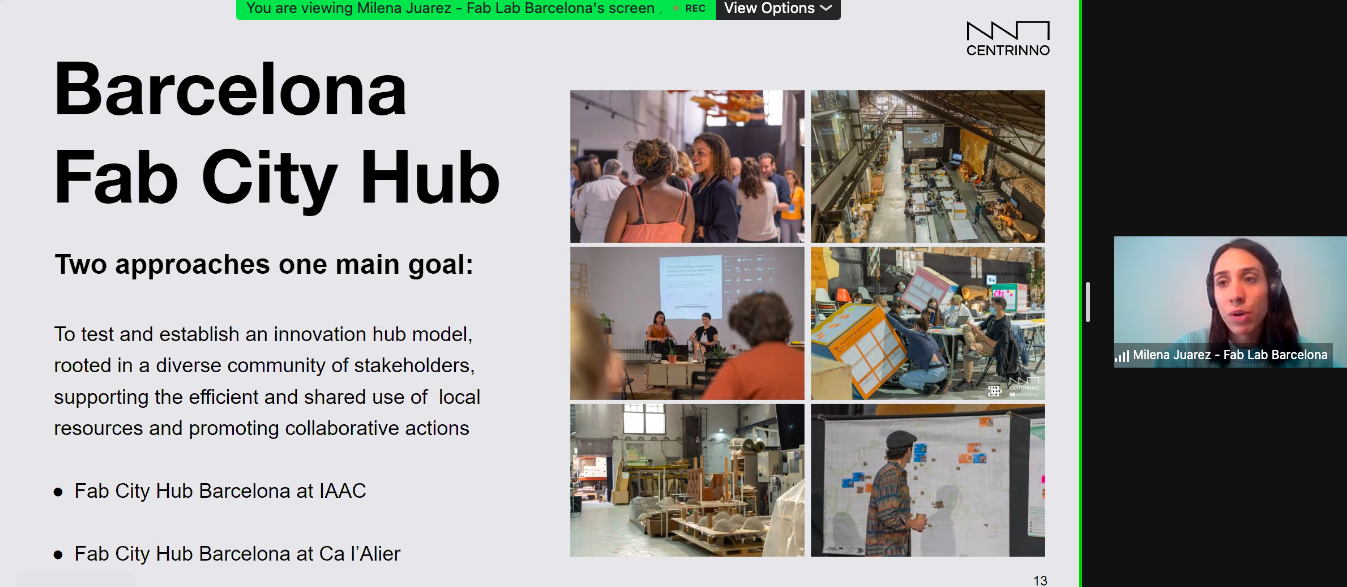

Around these two sites, the Paris pilot gathers complementary partners to form a collective able to investigate what could be the future of the urban food system in a big city like Paris.

- FabCity Grand Paris as the partner of the Fab city global initiative orchestrates the different activities in compliance with the principles and goals of the overall movement. Moreover, FabCity Grand Paris obtained the Qaliopi certification allowing them to conceive and conduct training programs.

- Vergers Urbains is an association that designs and implements edible nature areas in collaboration with the inhabitants. Besides their leading role in Le Jardin des Traverses, they are participating in various activities within CENTRINNO such as events, workshops and training programs.

- WOMA is a fablab anchored in the popular area of the 19th district. They contributed to several activities within CENTRINNO such as Farmbot implementation coding and events organisation.

- Ars Longa is a fabricative design agency aiming to think of the city as a source of know-how, tools and raw materials. They worked mainly with CENTRINNO on the MakeWorks Paris and Foodtrack platforms.

- Volumes is an agency dedicated to conceive creative and productive hubs. In addition to their role as work package leader, they collaborate on the Parisian pilot in the design and orientation of the sites.

- Sony CSL is an independent research lab focusing on how cutting edge technologies can help to solve environmental and social issues. Within CENTRINNO they work on robotics for micro-farming and the rehabilitation of past market gardening techniques in the actual urban landscape.

- Common challenges

Collectively, the Paris pilot team wants to create momentum by developing a series of curated educational programs, social gatherings and experimental projects to foster urban agriculture and food culture within citizens, SMEs, and institutional partners.

For this, we identified priority Challenges:

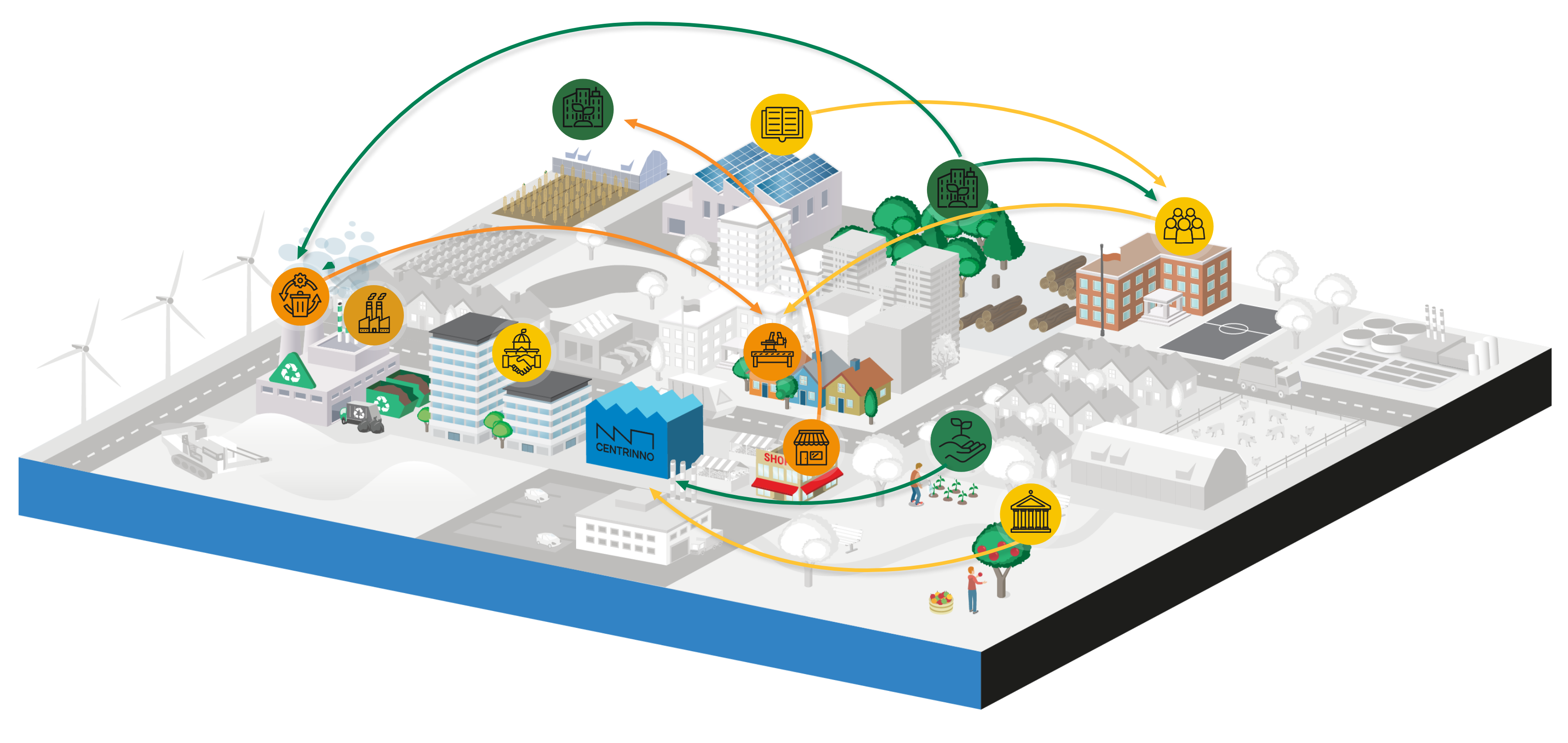

- First challenge will be to understand, coordinate and reach the entire ecosystem of foodlabs and urban agriculture initiatives in Paris to expand the impact of the experimentation around the 4 verticals of the urban food system : food production, food transformation, distribution and waste management.

- Secondly, establishing a creative and productive hub in a city with such a high real-estate pressure while maintaining a social approach is a challenge in itself, which Volumes already faced in the same area by created its first hub in 2015, Volumes Lab.

- Education and Training need to be inclusive and diverse with different programs for citizens and tourists with a focus on the return to employment through the acquisition of key skills to develop the urban alternative food system. The challenge will be to bridge cultures of traditional schools and new places of learning such as creative hubs: collaboration between those is a key factor of success.

We have therefore initiated activities to deal with these different challenges:

We first weaved properly what is at stake and what are the goals CENTRINNO looking to the current situations of each partners at the start of the program. For this we systematically contextualised the 5 CENTRINNO key concepts (Heritage, vocational training, innovative spaces, social inclusion and circular economy) through the sight of our local Parisian environment and the urban food system question.

We built a shared narrative to give consistency to our pilot named “Local farm, logical food”. We did a lot of historical researches to be able to show the legitimacy of our goal to reboot local food production, transformation and distribution in a dense urban landscape. We tested this narrative amongst various audiences (policy makers, makers and designers, researchers,…).

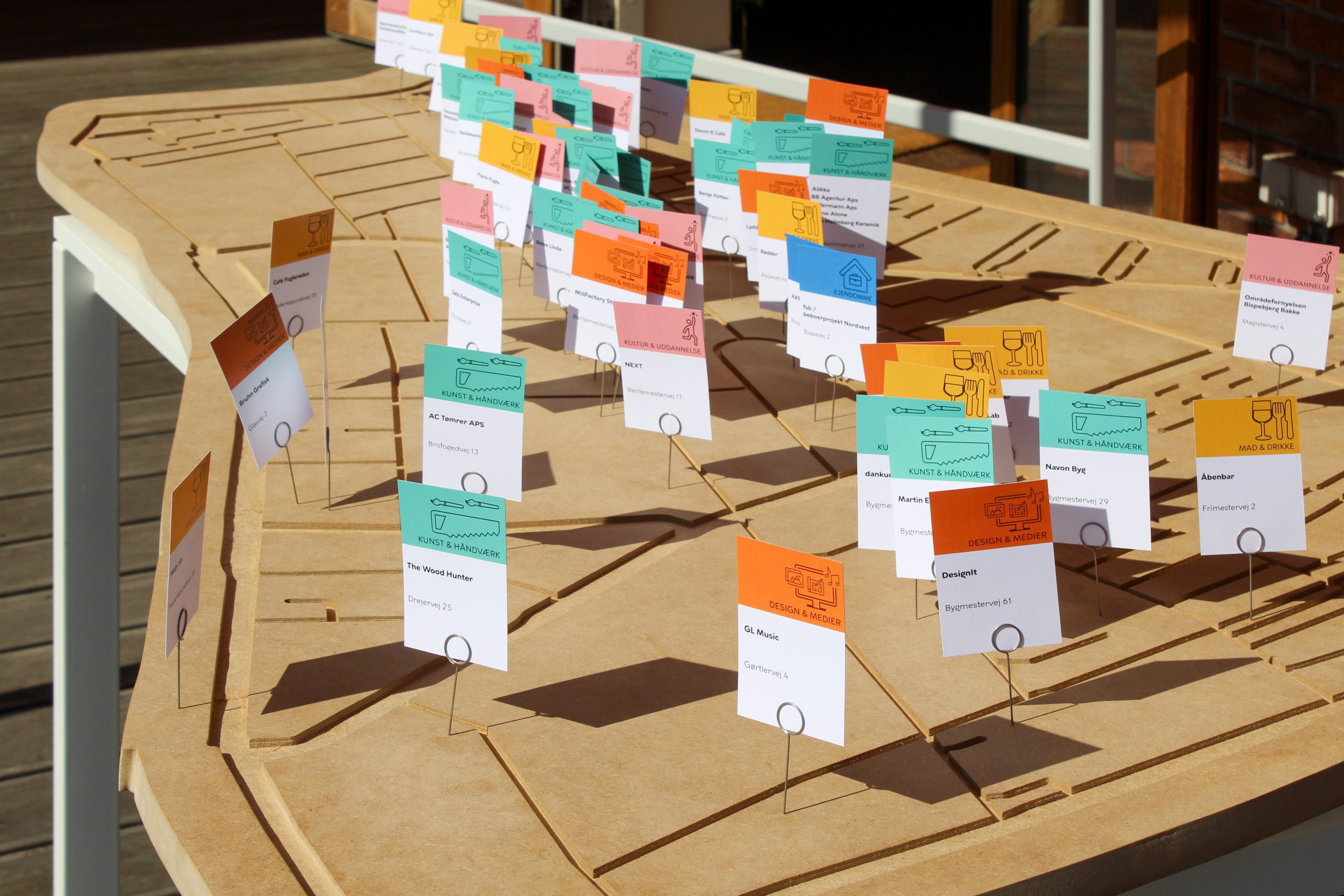

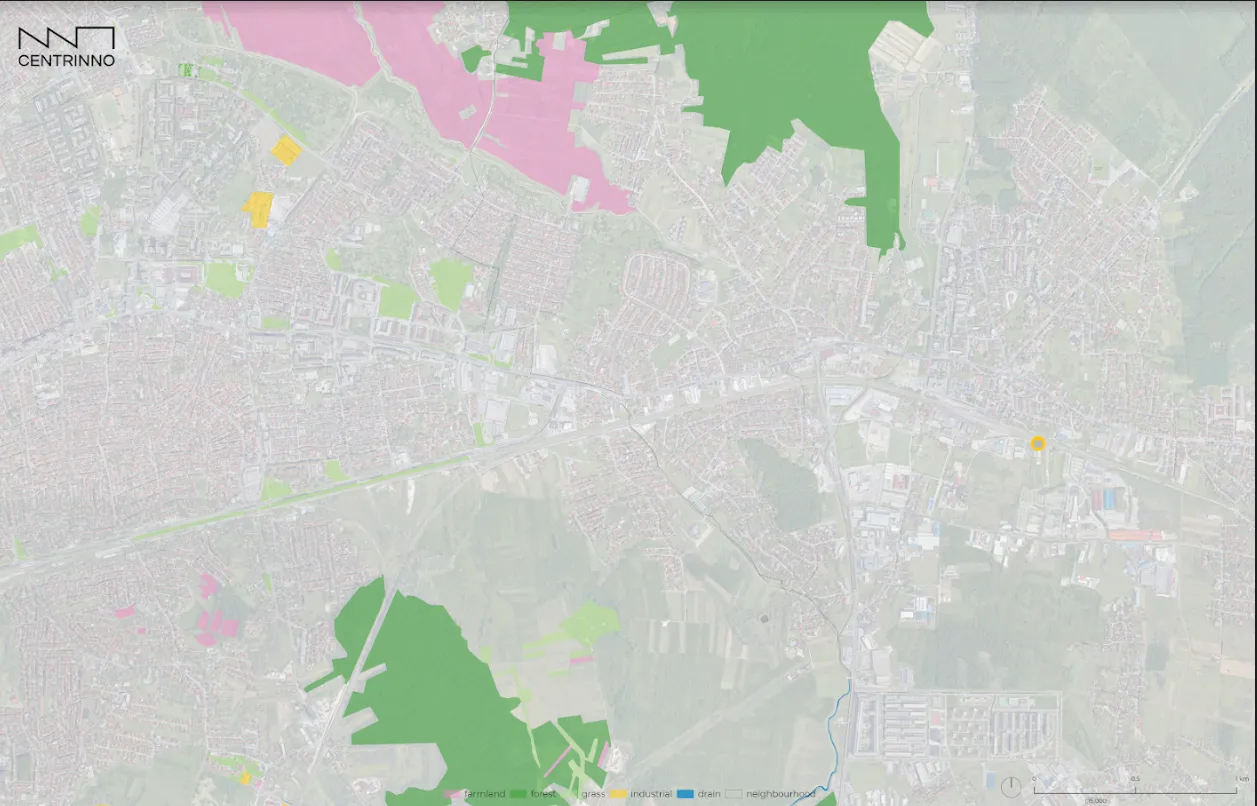

Then we took the open-source mapping software Kumu in hand to first map the actors of the urban food system with whom we wish to collaborate. We used it in a second time as a means of localizing the skills of the FabCity network in order to be able to respond quickly and efficiently to requests for training or distributed production.

We also worked on three activities around the notion of heritage : Food track (a pedagogical booklet and a digital platform to highlight the perpetuation of a common sense philosophy in the urban food ecosystem since 1850), Make Works Paris (showcasing Parisian food system actors and their relation with their work that will be specifically broadcasted as podcasts), Emotion Networking Sessions (we did several workshops dedicated to food).

Beta version of the Foodtrack platform

We developed or participated in two vocational training programs around alternative, sustainable and evolutionary food systems skills : Resiliences productives (participation) and Agriculture XYZ (conception).

Furthermore, we digged, through a survey and workshops the notion of Fab City hub and what it means for local productive actors such as makers, designers, urban farmers. Hand in Hand with the Volumes team and the real estate cooperative, Oasis 21, we gathered around strategy meetings to tackle the last pain points before the opening. And all of that in a close discussion with Food and sustainability Paris department.

The Fabcity Hub Paris opened in February 2022. Despite the economical pressure, they succeeded into welcoming only structures part of the social and sustainable economy allowing to envision future synergies both local and at the city scale.

Our partners Sony Lab, WOMA and Vergers urbains reunite to work on the prototype of an urban farming rover that was presented at the Maker Faire Rome in October. Moreover, they work on an experimental farming project to test the possible reactivation of the “french method” (urban agriculture technics developed in the XIXth century in Paris).

Finally, we managed an event programmation to spread the word both on CENTRINNO and on the methodologies and activities we work on (Ouishare Fest, Fabcity Camp Paris, WOMApero, Fabcity hub Paris animation strategy). It allowed to test and adapt some of the methodologies provided by the CENTRINNO consortium like the Emotion Networking workshop. We organised round tables with experts and field actors around key subjects like :

- Towards local and sustainable food, from field to plate > Alternative food system – Ouishare Fest 21 – June 25,2021

- MATERIAL – The city as a deposit > circular economy – FabCity Camp Paris – October 21, 2021

- Towards complementary food systems > circular economy – FabCity Camp Paris – October 21, 2021

- Urban agriculture through the prism of technology > WOM’APERO – October 28, 2021

- Citizen collectives for the safeguard of agricultural land > WOM’APERO – February 3, 2022

- Eat the City – A conversation with MakeWorks Paris alternative food systems actors > FabCity Hub event – July 5,2022.

Eat the city at the Fabcity Hub Paris

Emotion networking session at Fabcity Camp Paris

Even if these different activities may seem at first sight disparate, they respond to a common objective to study the best way to raise awareness and activate the dynamics of a new urban food system. They allow both for us to gain knowledge to plant roots that will last after the CENTRINNO program and for our stakeholders to reconsider their professions in the light of the new challenges of the city.

3. Don’t skip the lessons

During these two past years of working on CENTRINNO, we adapt our strategy due to the lessons learned. What is interesting to notice is that there is two kind of changes that our pilot experienced : some natural and evolutionary changes that we didn’t realise at the moment but that came progressively and collectively because of our better knowledge of the topic and the context. And some reactive changes due to specific situations or delays we have encountered.

In the first category of changes, the evolutionary changes, we can highlight that we totally discovered how the fact of showing the bound between past and future can be a powerful tool to work on the present. Despite the fact that we minimised it at the beginning of the project, we see today that having the cradle of modern urban agriculture in Paris with the “french method” is a perfect way to envision how to gather actual stakeholders to reinvent and to develop a new alternative food system. The common sense of these 19th century market gardeners resonates deeply with the environmental issues of the near future and makes the conventional agricultural model even more absurd. Hopefully, we are convinced that the historical soil of our pilot is a perfect field test to try the same approach.

Besides, we also discovered that long term evolutions begin by education. Therefore, the vocational training actions take today a much more larger place in our roadmap. The first benefit of it is of course to create a skilled workforce to improve the way we produce, transform and distribute food in the city. But also, and this is essential, designing training programs allows us to have a reflective approach to what we do as professionals of the relocation of production to the city and the alternative food system. Thanks to that, we are able to see dead ends or hidden opportunities with more accuracy.

In the second category of changes, we faced the challenges inherent in opening a place that is both inclusive and sustainable and at the same time economically viable. This leads us to several conclusions. First, keeping the economic model in balance – in a city with a tight real estate market – is even more difficult in times of health or energy crisis. This instability creates difficulties that are more quickly perceptible for small economic actors (craftsmen, market gardeners…).

Secondly, a place to live is above all a community in action that animates a project before, during and after the opening of a place. And we see the coupling in this process of creation, cohesion and animation. Finally, it seems to us that an alternative and sustainable urban food system must be based on a food culture of the citizen. Urban agriculture can play a role in educating the inhabitants, especially the youngest, to understand the origin and the stakes of what they eat.

4. Conclusion: a lot done and a lot to do

After these two years of work and learnings, we know now that we have a lot to do to match our goals. The next chapter will be to set the stage of a remaining ecosystem sharing the same vision in the way we handle food not only in Paris but also by showcasing our replicable learnings among other cities.

The main conclusion we can draw is that when it comes to the Parisian alternative food system, we are more about a distributed ecosystem whose strength is its diversity. Our role is to create connections between the different actors to accentuate synergistic and circular dynamics. This is why, even if we are lucky enough to open two sites, in a nearby neighbourhood of the north-east of Paris, that can serve as catalysts, we must first find a way to implement the logic of pooling resources and sharing knowledge.

We also see that we must remain humble in our way of dealing with our topic because we are drawing a possible path among others. We cannot impose ways of doing without taking into account the context and the heritage that determines it. Some experiments may be extended and create roots, others will have to be reconsidered. This is part of any research work.