BLOG

Deep roots: on the (hi)stories of woodcraft

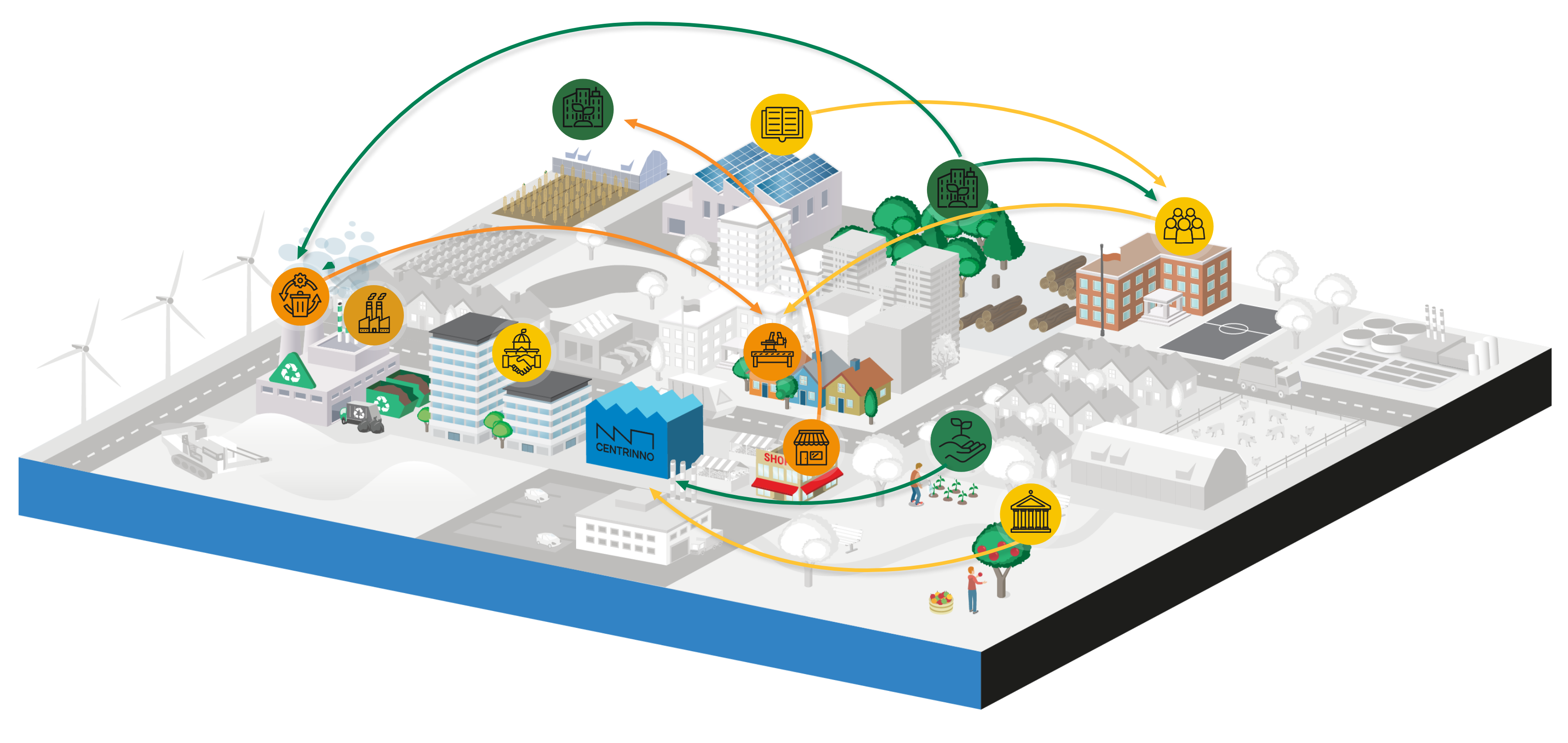

The CENTRINNO Living Archive is full of stories speaking to the complex and interesting ways in which the past has an ongoing impact in the present and future. Many stories are characterised by a relationship to different materials, as is befitting the patchwork of histories that centre around places of production. This blog post explores the materiality of wood, and the way that it might facilitate the telling of different stories according to different contexts.

By Harry Reddick

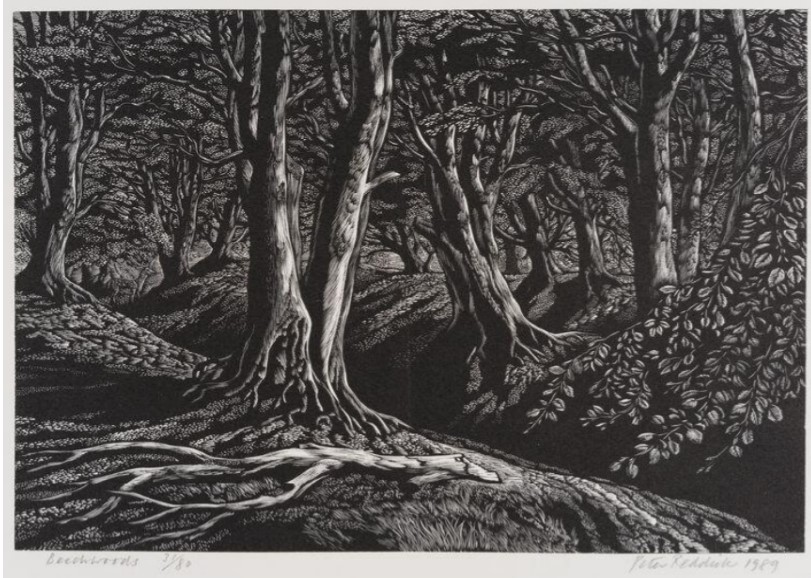

Peter Reddick, Beechwoods, 1989, Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Climbing the branches of history

My grandfather, Peter Reddick, was a wood engraver who did illustrated editions of many well-known British poets such as Thomas Hardy and William Wordsworth. Clearly, he was someone with a special relationship to wood, and, further, the storytelling materiality found within wood. (In fact, when we were younger, he would give us christmas cards with engravings signed ‘with love, Treebeard’ in reference to the booming-voiced character from Lord of the Rings). But what is it about wood that is so special? Why can wood facilitate the fluidity and movements of emotion, time, histories, locality, connection, personality, cartographies, and more besides? In this blog I spend some time exploring different examples of how wood is understood and reimagined, within and beyond the examples found in the CENTRINNO Project.

Engraving by Peter Reddick. Image taken from William Wordsworth, ‘Elegiac Stanzas’, from Selected Poems, (London: Folio Society, 2020), 144.

Stories beyond the rings

It is common knowledge that if you were to walk into a forest and cut a tree across its width, it would become possible to see a set of concentric circles spreading outwards from its centre within the ring of outer bark, showing how many years the tree has been growing. These rings are not simply markers of time (though that would be a remarkable enough natural feature). According to climate.gov, the ‘underlying patterns of wide or narrow rings record the year-to-year fluctuations in the growth of trees. The patterns, therefore, often contain a weather history at the location the tree grew, in addition to its age.’ [1] Forests speak then, not only of their own lifetimes and their own stories, but also of the conditions of the climate which facilitated its growth, as well as any other relevant localised environmental impacts like pollution, ecosystemic change or biodiversity loss. There is a kind of permanence to the materiality of trees, in the way that history becomes literally ingrained in the wood.

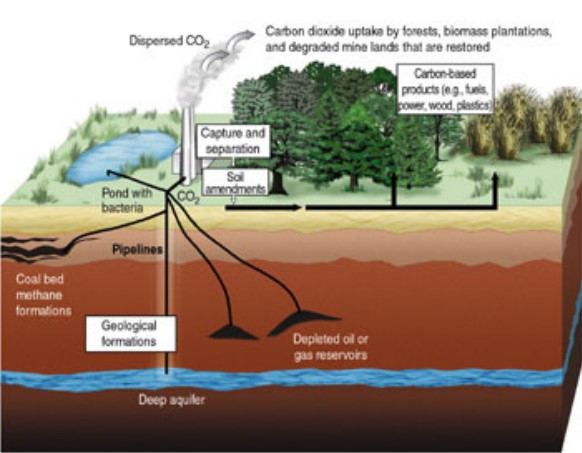

Understanding the materiality of wood in different ways could be a helpful tool in attempts to move towards more sustainable ways of living. For starters, this historical imprint of previous climatological developments can be understood in a forward-facing way as well, in the sense that trees are also a vital part of future endeavours to draw down carbon in the atmosphere and present alternative energy sources. As Holly Jean Buck’s tremendous book After Geoengineering: Climate Tragedy, Repair, and Restoration argues, trees and other plants ‘take up carbon, but… can also be used for storing energy’. [2] Taking carbon into trees also allows for the process of separation and sequestration of the carbon underground, a vital part of atmospheric carbon reduction planned in the wake of the environmental impacts of industries. [3] The wood of trees thereby takes in the impacts of industrial activity of spaces like the pilot sites of the CENTRINNO, both of the past and what still occurs today. We can thus understand trees as carbon heritage: an ecological entity whose environmental impact ‘must be directed not just into the future, but into the past as well, thereby placing climate intervention into historical context’. [4]

Carbon Capture Sequestration and Storage diagram, rendering by LeJean Hardin and Jamie Payne, image credit: Wikicommons

In such a vision, wood takes on a characterisation of permanence rarely associated with the rapid and ravenous consumption of wood and other biofuels for the manufacturing processes of modern cities. Understanding wood this way points to a more sustainable use of natural resources, or even a perception of them on the scale of deep time. [5]

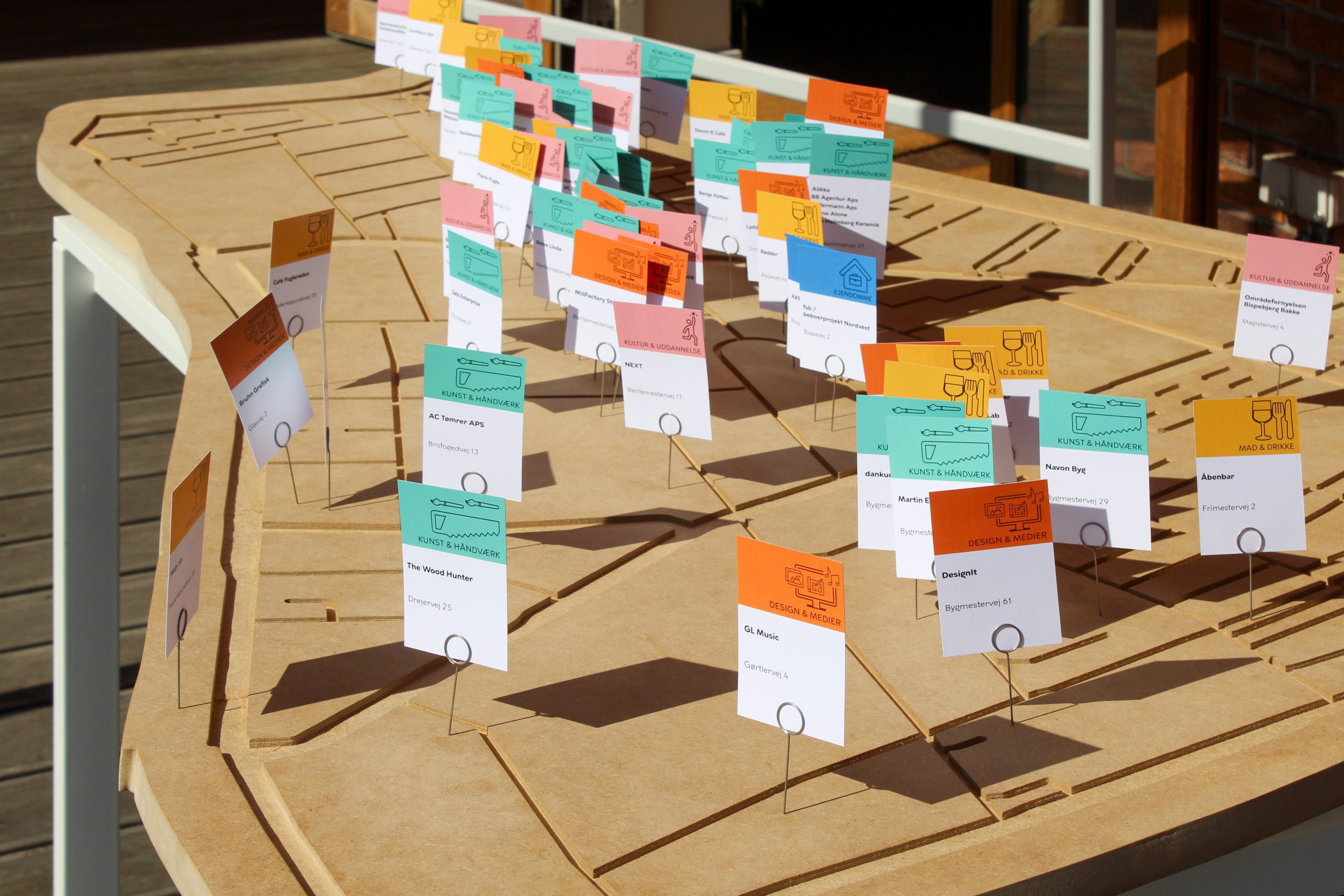

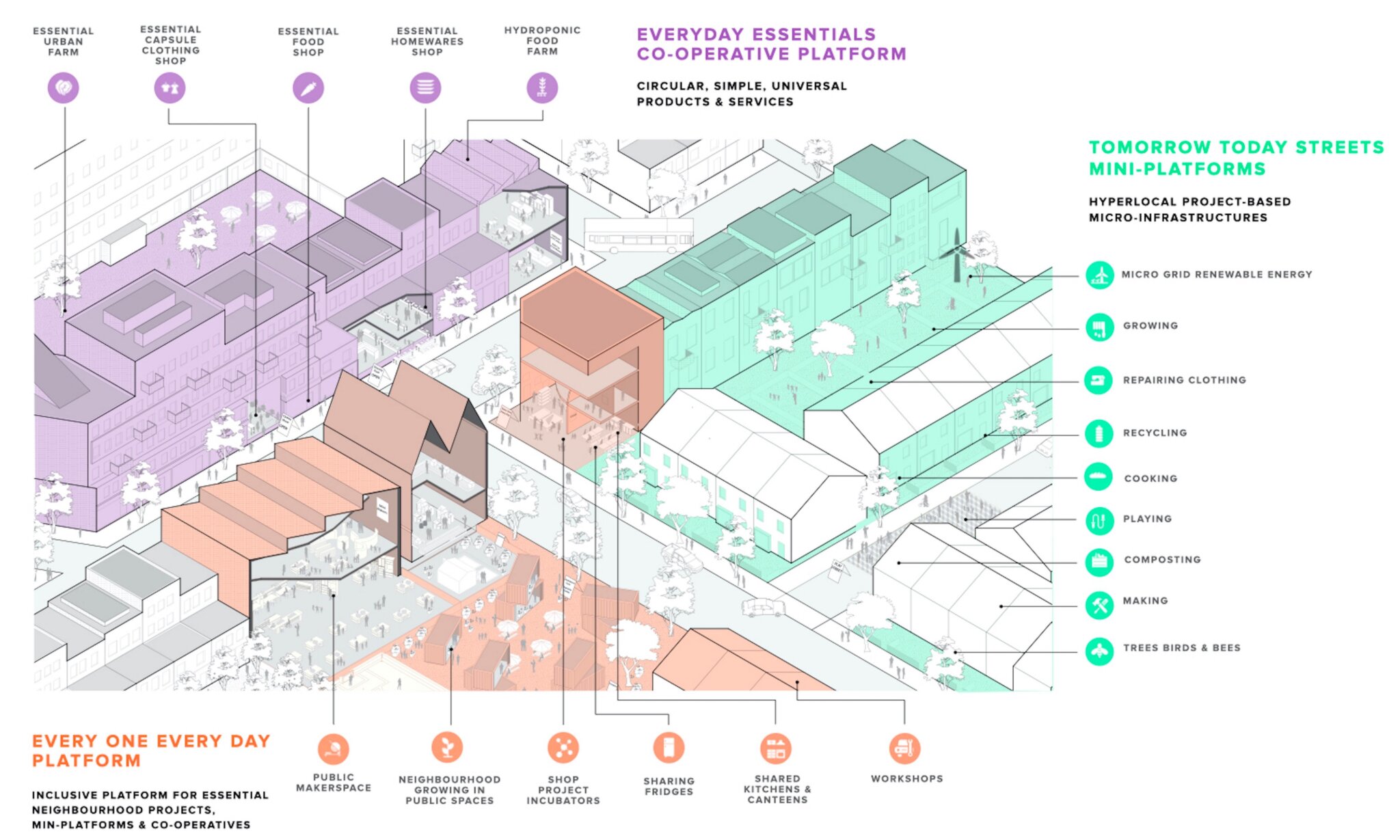

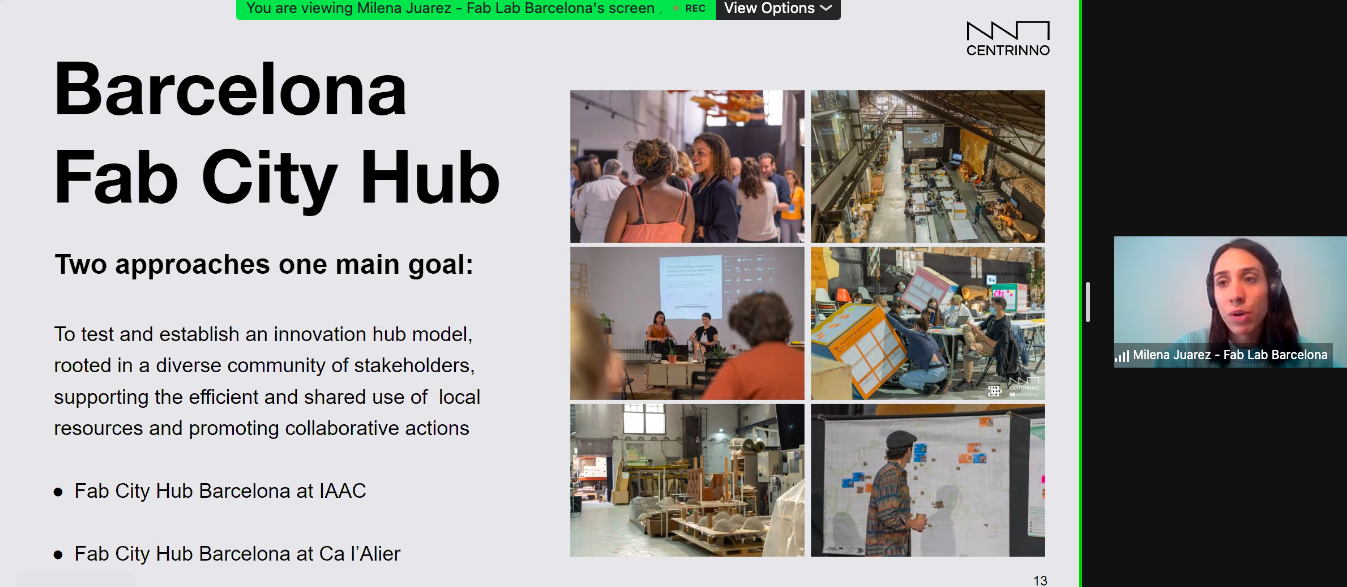

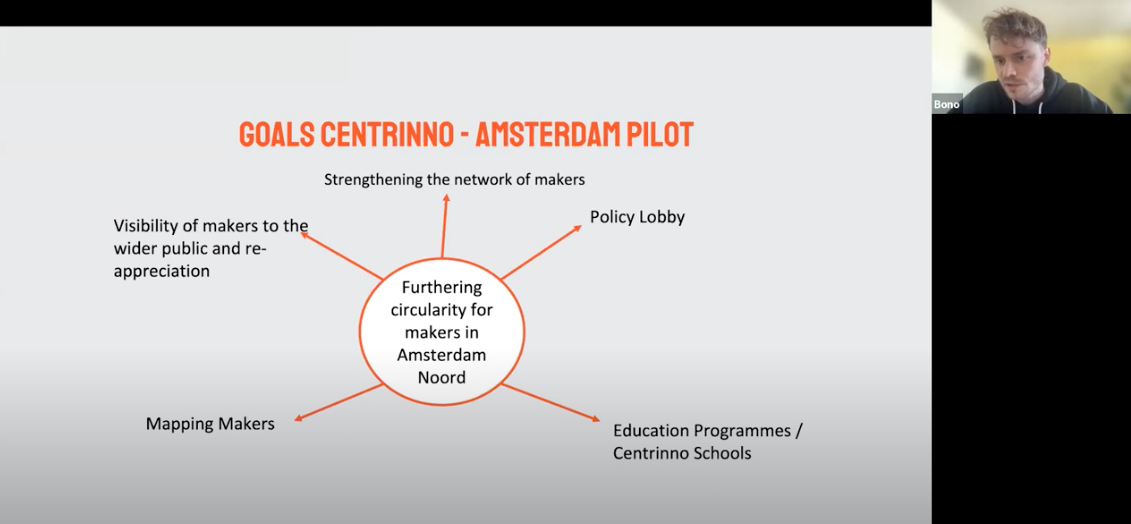

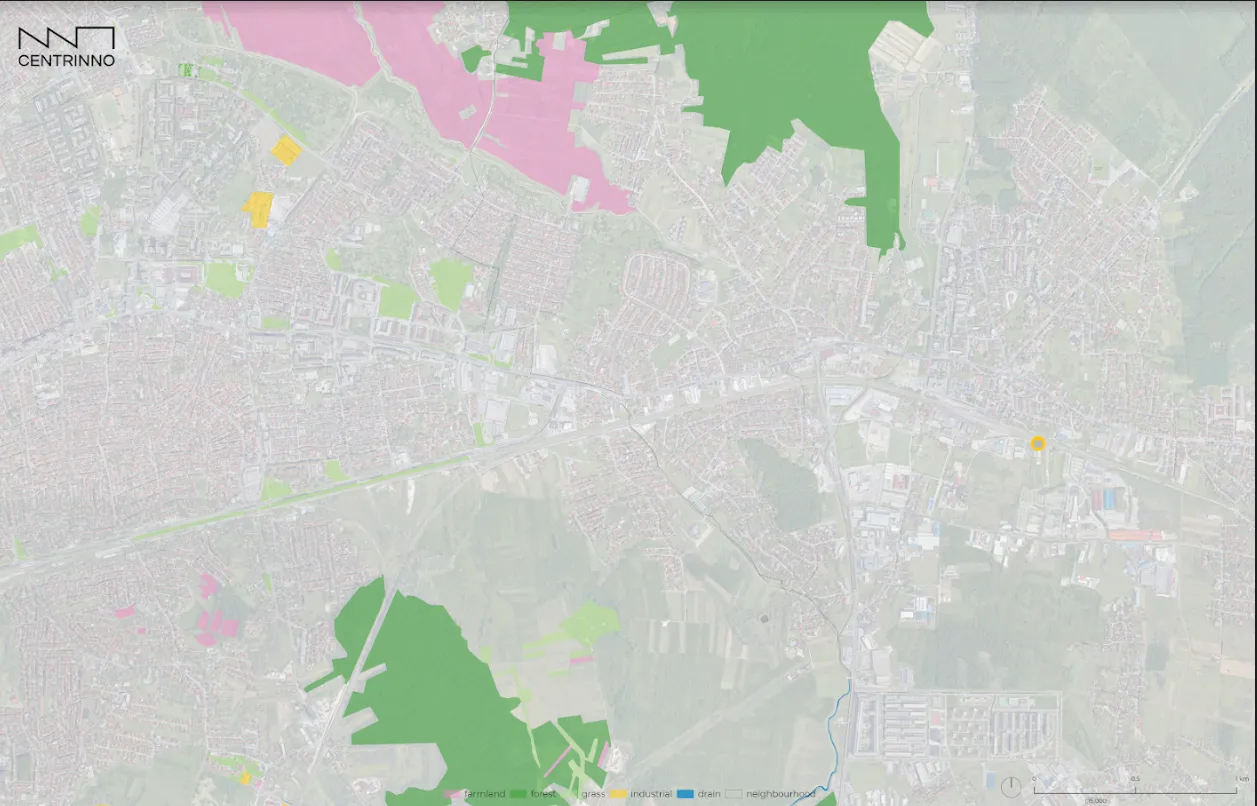

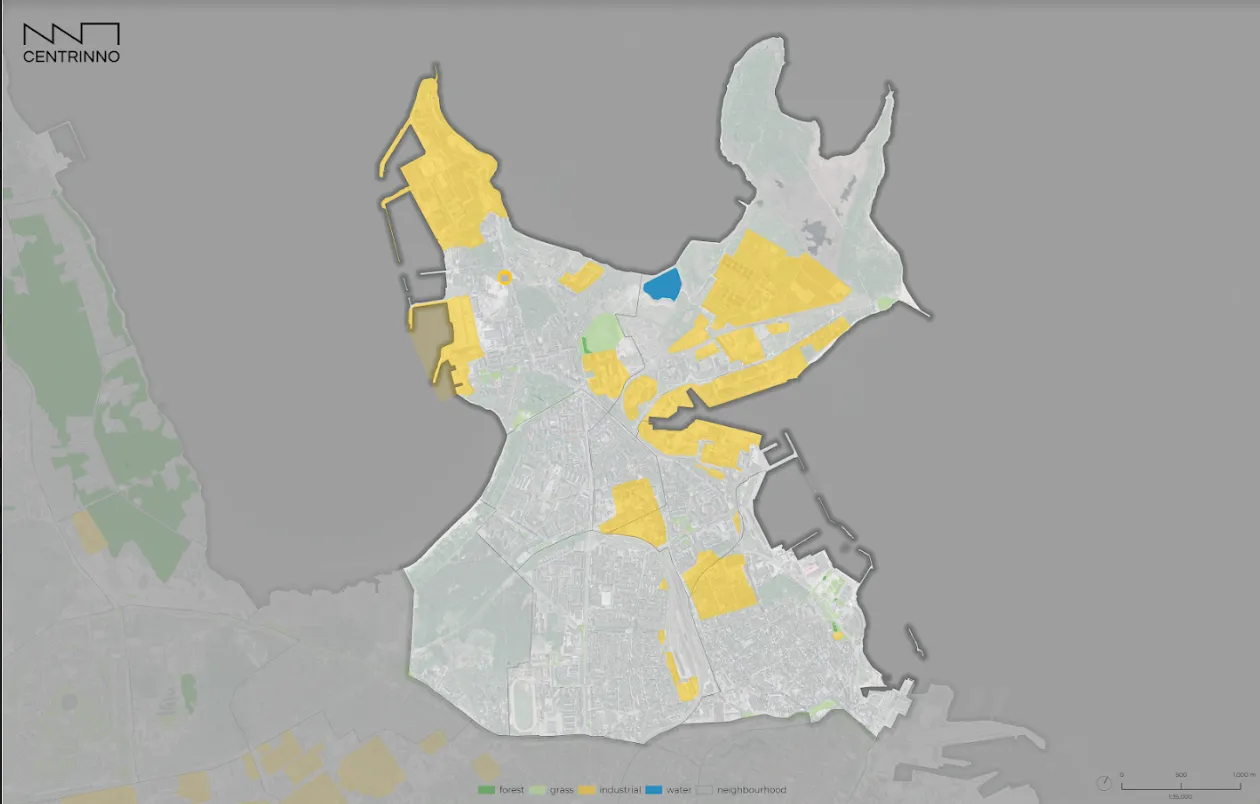

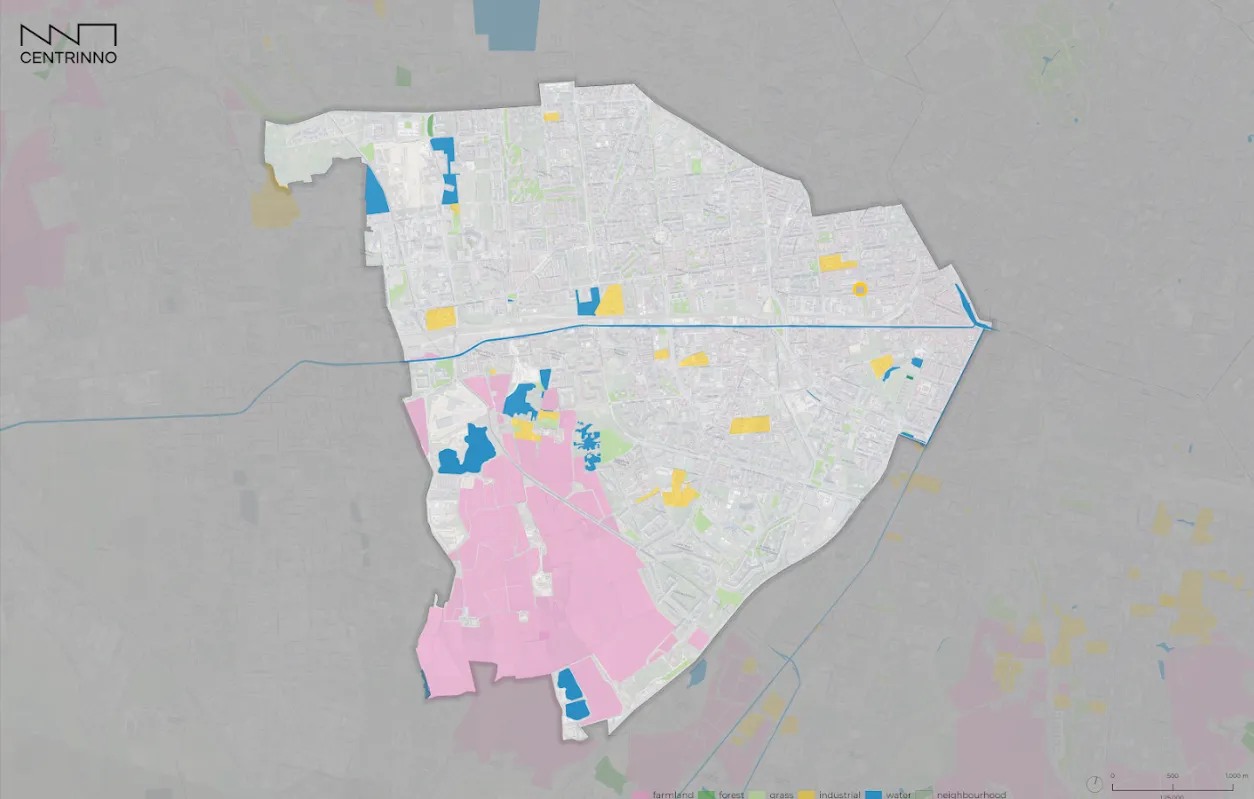

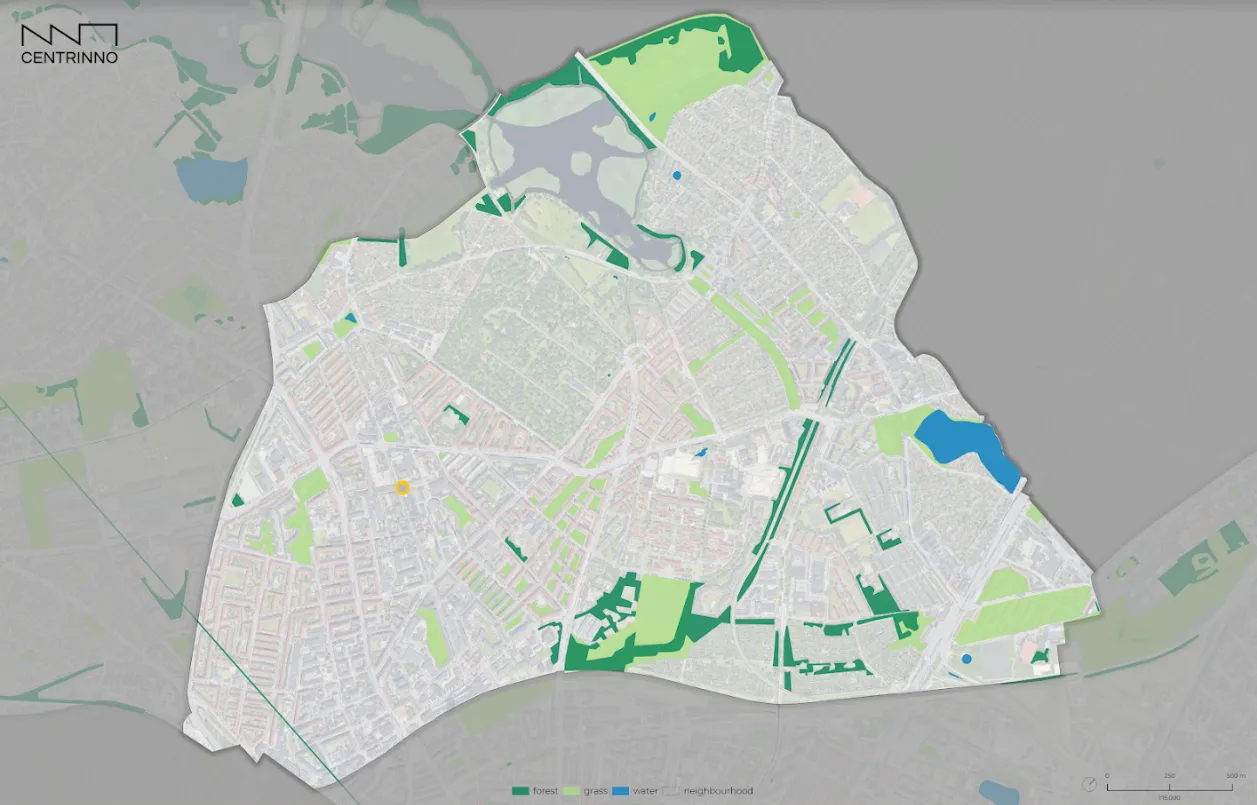

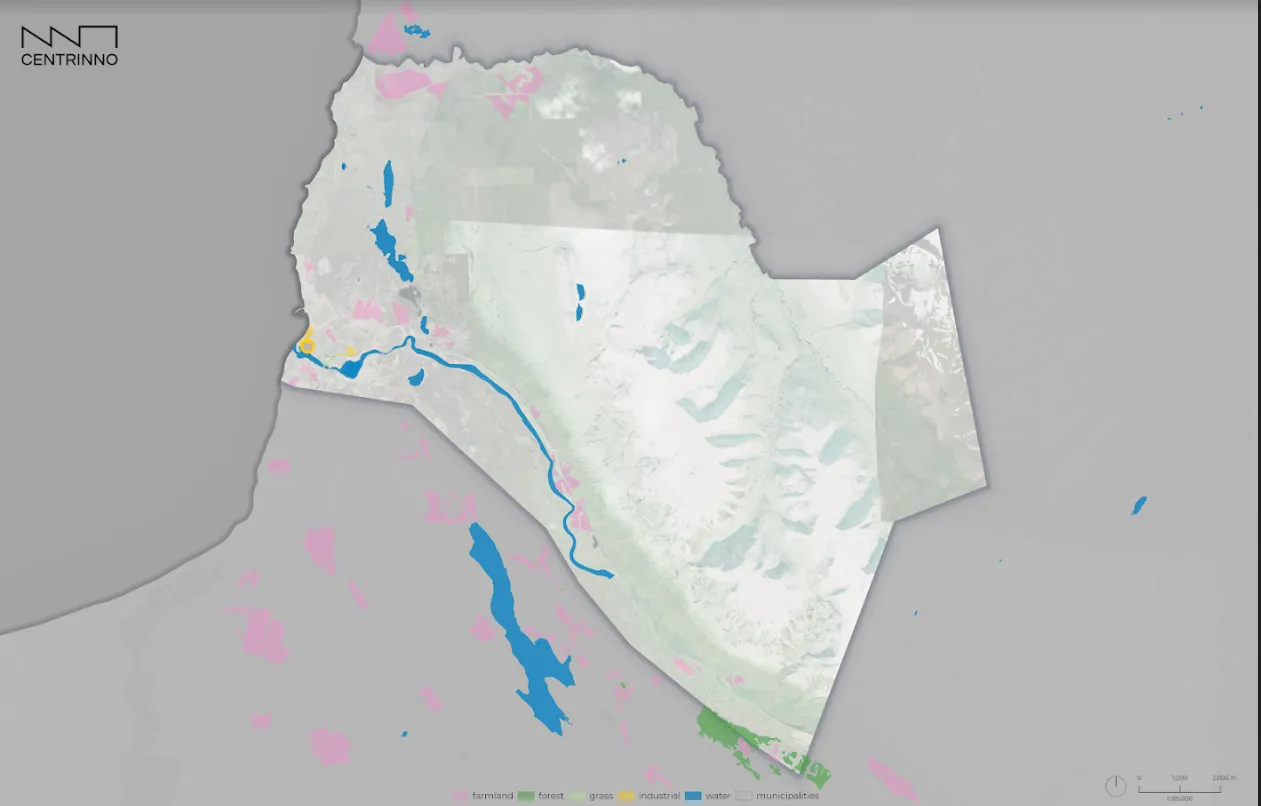

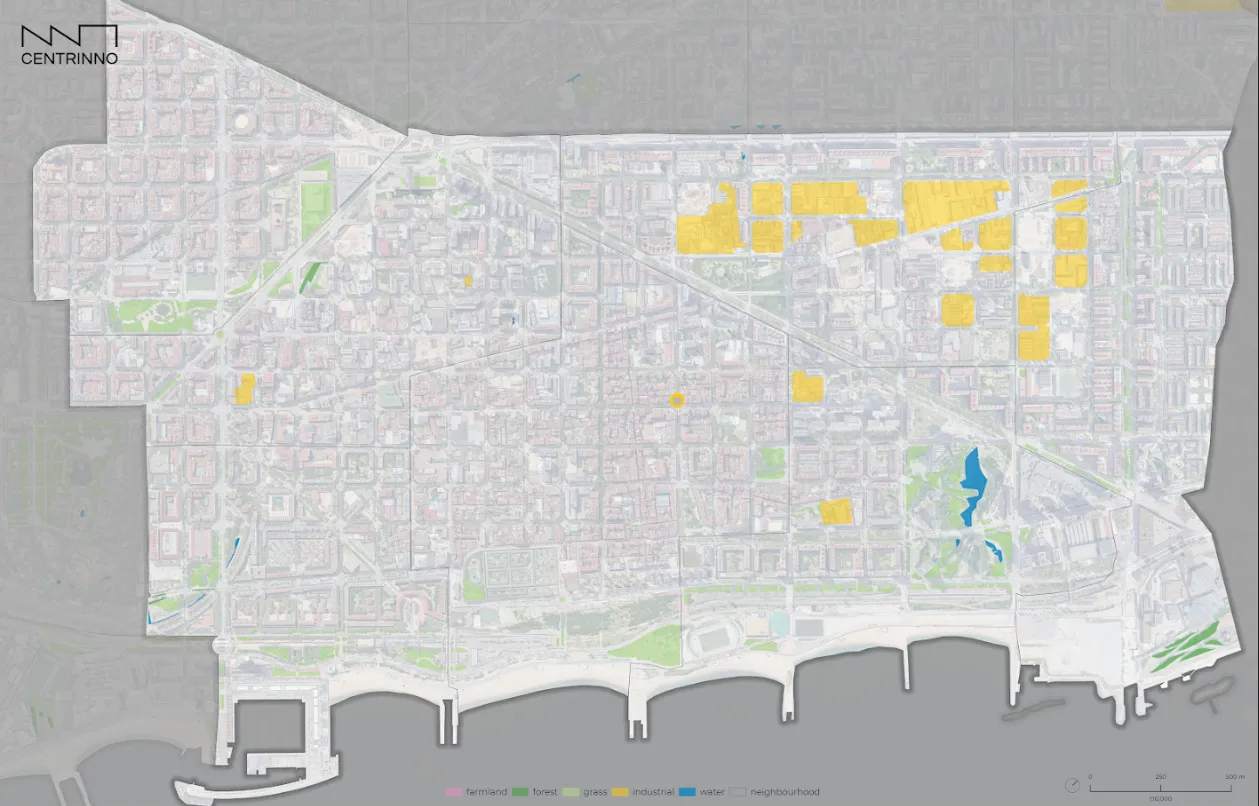

Perceptions of wood constructed from this necessary altered temporal basis is also something implicated in some examples from the CENTRINNO pilots, which we will explore below. These examples come from the Amsterdam, Barcelona and Geneva pilot teams, and their stories in the CENTRINNO Living Archive, and show how wood is a material with much to offer heritage discussions.

‘Waste wood does not exist’

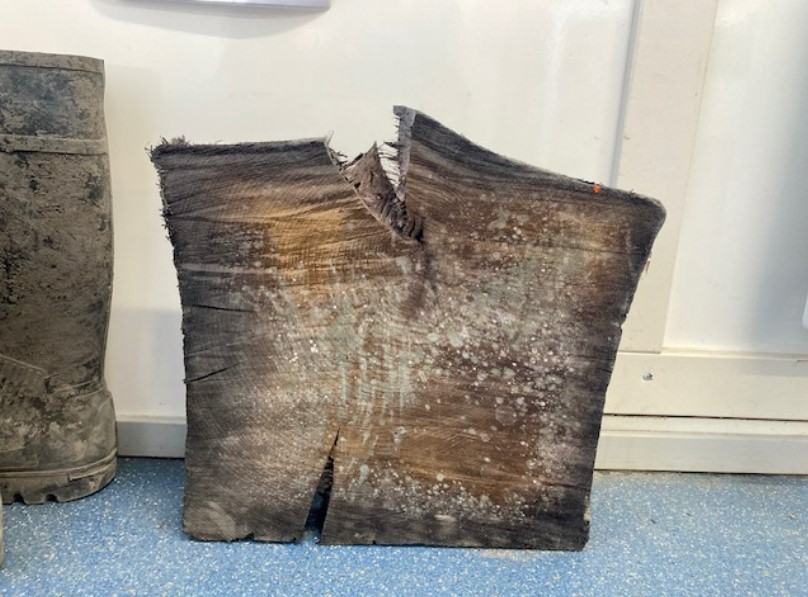

Generatie Groen (Generation Green) operate from a small workshop in Amsterdam Noord. As described in a Living Archive story about the initiative, carpenters (and founders of Generatie Groen) Harvey Hendriks and Mees van de Ness operate from the principles that ‘waste wood does not exist’ and ‘waar wij voor staan is waar wij op staan’ (what we stand for is what we stand on)’. The two ‘make new products like art and wooden furniture’ via ‘re-us[ing] discarded and residual materials…. [and] using every last scrap in their work.’ An example of this is a piece of wood the pair worked with that was ‘from the 1400s, that came from a water lock near Monnickendam, a city in North Holland.’ [6] That’s a piece of wood that is around 600 years old! Being part of the construction of the water management systems that comprise the Dutch infrastructural basis, such an item is clearly one of heritage, carrying with it national designs upon the elements: architectural visions of a different relationship to the systems of nature.

Ancient wood from Monnickendam, North Holland. Image credit: Amsterdam pilot

In Barcelona meanwhile – a location historically less in need of designing its entire national infrastructure to be protection against flooding – a similar initiative has sprung up, as shown in the story Likenwood: Connecting with Nature through Woodcraft. Likenwood, an organisation operating out of Poblenou, is ‘a team and a family dedicated to [the] design and manufacture [of[ wooden objects… seek[ing] connection with nature through furniture, using all the senses to appreciate and live it.’ [7] The organisation also works on a no-waste basis, making sure that smaller offcuts of wood are accordingly used to make smaller products or, as a last resort, used as fuel in local restaurants. The permanence afforded by the material nature of wood is also part of the thinking underpinning Likenwood’s work: ‘We like the idea of being able to make furniture that is able to last for many generations, but at the same time is made from renewable materials’. [8] That the products made in Likenwood and Generatie Groen use local supplies, rather than shipping wood from across the world, is a further benefit. The initiatives therefore ‘support and sustain the local (circular and equitable) economy’, as has been argued for in the CENTRINNO blog post ‘Manufacturing in Cities’ [9] To work with what is available; to be able to keep renewing; to be able to work across generations: these are principles of a sustainable future, informed by the lessons of the past. Holding true to these principles, and finding them within the grain of wood, offers some hopes for the future.

Likenwood Workshop, image credit: Fab Lab Barcelona

Timber transference

Wood then, in the hands of crafters such as those from Generatie Groen and Likenwood, as well as CENTRINNO partner Hout-en Meubileringscollege, is demonstrated to be, once again, a material that can be seen as a carrier of histories. In the forest, the wood of the trees may carry carbon and the impact of the apparently-removed industrial, urban past. In the workshop, wood could carry the promise of a different world: either of infrastructural constructions that would shape the trajectory of a nation irreversibly, or of furniture made today that could last long enough to witness such change across generations. In another example, this time from the pilot team of Geneva, wood is demonstrated to hold within it further qualities, such as care, and the possibility for politicised interpersonal relationships.

The Living Archive story Something to Keep shares the story of an unnamed, ‘very elegant and enthusiastic lady’ of 90 years old, and a gift she received upon her arrival at the Zone Industrielle de Charmille (ZIC) community of makers and artists. This worker felt connected and part of a community when, over 30 years ago, she was given a welcome gift of a wooden coffee table by her carpenter neighbour. Over time, she developed some concerns about the possibility of the artistic community continuing to operate in the area at the hands of the municipality and their ‘hovering’ threat of eviction. However, the sense of connection between the labouring and making community acted, for her, as a bulwark against the insecurity-inducing whims of the municipality, with this sense of empowerment somehow feeling enshrined within the wooden table itself. Further, the table served as a symbol as to why it is so ‘important that the ZIC area has been to keep production in the city alive.’ [10]

Geneva’s welcoming community of makers. Image credit: Geneva pilot team

Splintered futures

If we were to return to one of the questions beginning this blog – ‘what is it about wood that is so special?’ – perhaps it is worth turning to another Peter – Peter Korn this time – , for an answer. Korn’s book Why We Make Things & Why It Matters: The Education of a Craftsman argues that the act of making with materials such as wood denotes ‘one fundamental truth: we practice contemporary craft as a process of self-transformation’. [11] Certainly, there are some aspects of many modern cities, some ways of living, that are long overdue urgent transformation. The approach to heritage within the CENTRINNO project allows for different dimensions of materials like wood to be apprehended, or for perceptions, understandings and usages of them to transform. Trees are not just ecological entities, but carbon sinks. Seeing the wood through the trees means not just thinking of wood as a raw material, but as a material in which care and transference can be embodied, in the form of crafts or historical objects.To allow for care to indeed be transferable to future generations – as the CENTRINNO project strives to do – learning from wood and applying the lessons in its splinters might well be a good place to start.

References

[1]-https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/how-tree-rings-tell-time-and-climate-history

[2] Holly Jean Buck, After Geoengineering: Climate Tragedy, Repair, and Restoration (London: Verso Books, 2021), 38.

[3] ‘LandCarbon’, Land Change Science Program, October 10, 2018. https://www.usgs.gov/programs/land-change-science-program/science/landcarbon

[4] Buck, After Geoengineering, 16.

[5] ‘Deep Time’, Vienna Anthropocene Network, https://anthropocene.univie.ac.at/resources/deep-time/

[6] [Amsterdam story]

[7] ‘Likenwood: Connecting with Nature through Woodcraft’, Barcelona Pilot, CENTRINNO Living Archive, 2022, https://livingarchive.centrinno.eu/story/likenwood-connecting-with-nature-through-woodcraft

[8] ‘Likenwood’, Ekohunters, https://www.ekohunters.com/likenwood/

[9] ‘Manufacturing in Cities’, Make Works, CENTRINNO Blog, 21st February 2022, https://centrinno.eu/blog/manufacturing-in-cities/

[10] ‘Something to Keep’ Geneva Pilot, CENTRINNO Living Archive, 2022, https://livingarchive.centrinno.eu/story/something-to-keep

[11] Peter Korn, Why We Make Things & Why It Matters: The Education of a Craftsman, (London: Vintage, 2013), 7.