BLOG

Artefacts of change: exhibiting past, present, and future in CENTRINNO

Central to the idea of heritage in its modern conception is the notion of the exhibition. In CENTRINNO, pilots used a specific heritage methodology developed within the project in order to underpin the creation of exhibitions showcasing the history (and beyond) of their local context. This blog post looks at some of the ways this was achieved.

By Harry Reddick

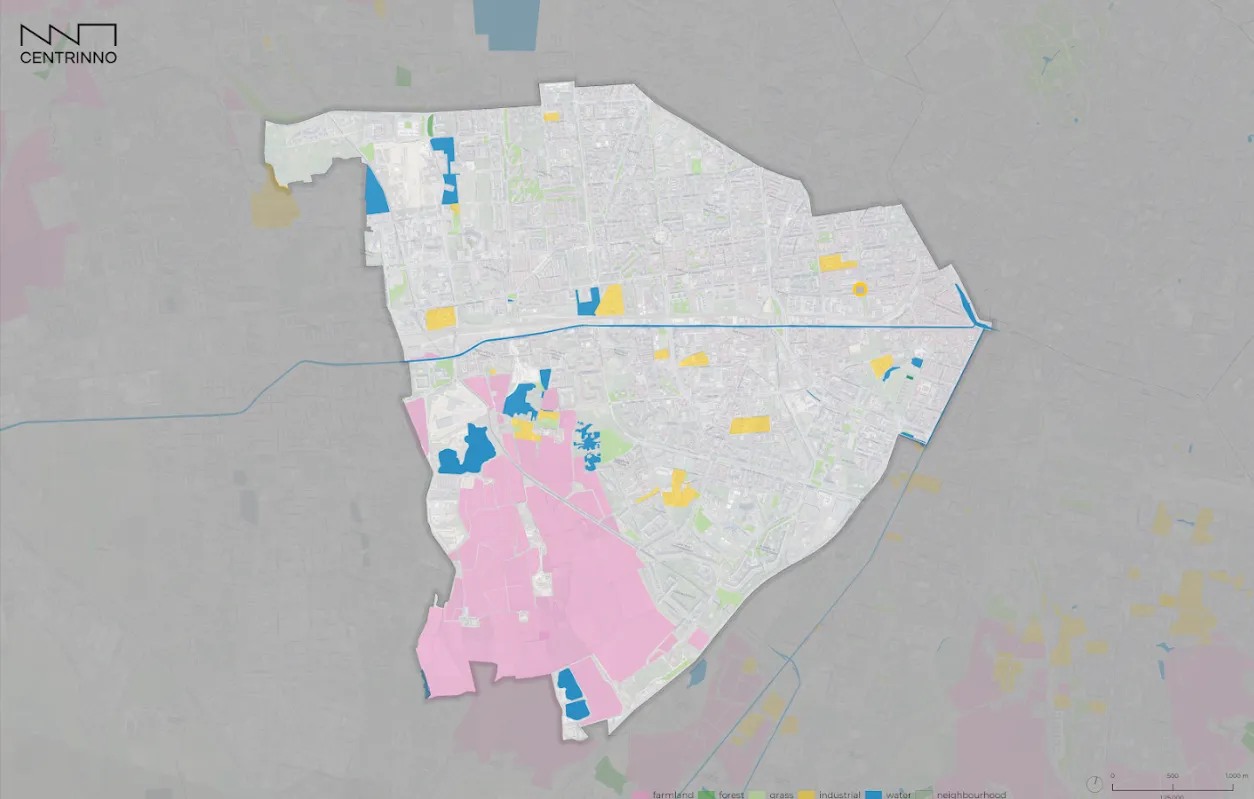

The CENTRINNO Living Archive: CBA, with an explanation

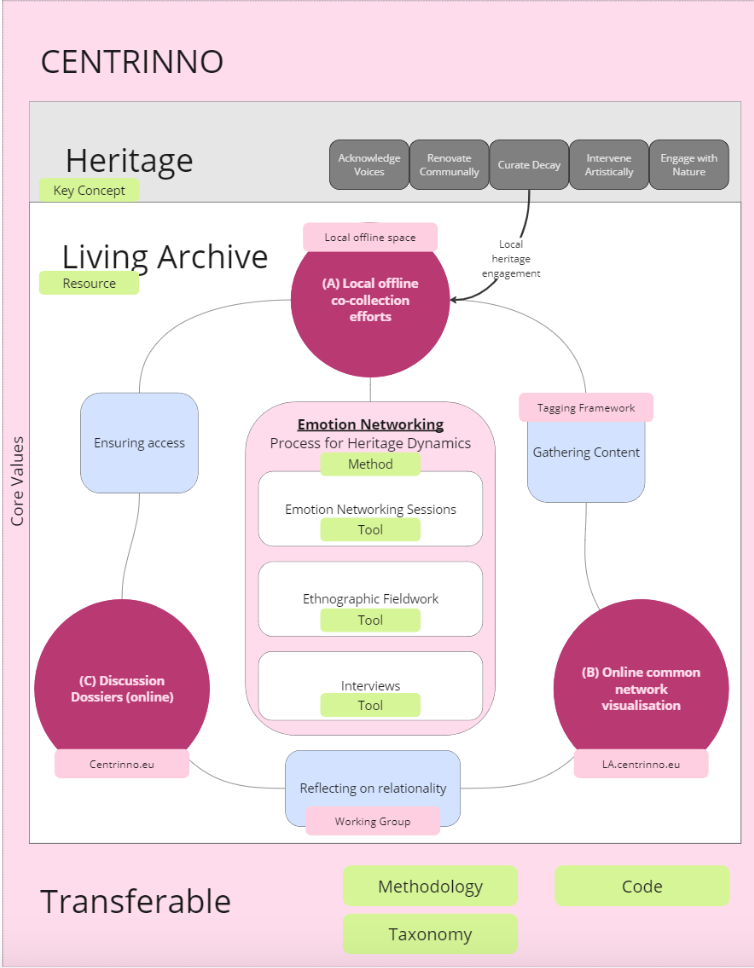

The heritage work undertaken in CENTRINNO, enshrined in the project’s Living Archive, is comprised of 3 main components, organised in an ABC structure. To take an unconventional route of explanation, this text, part of the series of blog posts on the CENTRINNO website, forms part C of the Living Archive, whereby the content and data that has been collected by each pilot team is analysed in a series of longer-form written pieces, that show interesting lessons to be taken from the gathered material. The Living Archive website itself, an online repository of heritage items, stories, speculations, media, and more, as well as a networked map showing the connections between these, forms part B. This leaves part A, which, unsurprisingly forms the foundation of the Living Archive, as arguably the most classically-recognisable example of heritage-making: the exhibition.

Fig. 1 – Detailed framework showing the Living Archive ABC structure, as delineated in the Living Archive Beta Version.

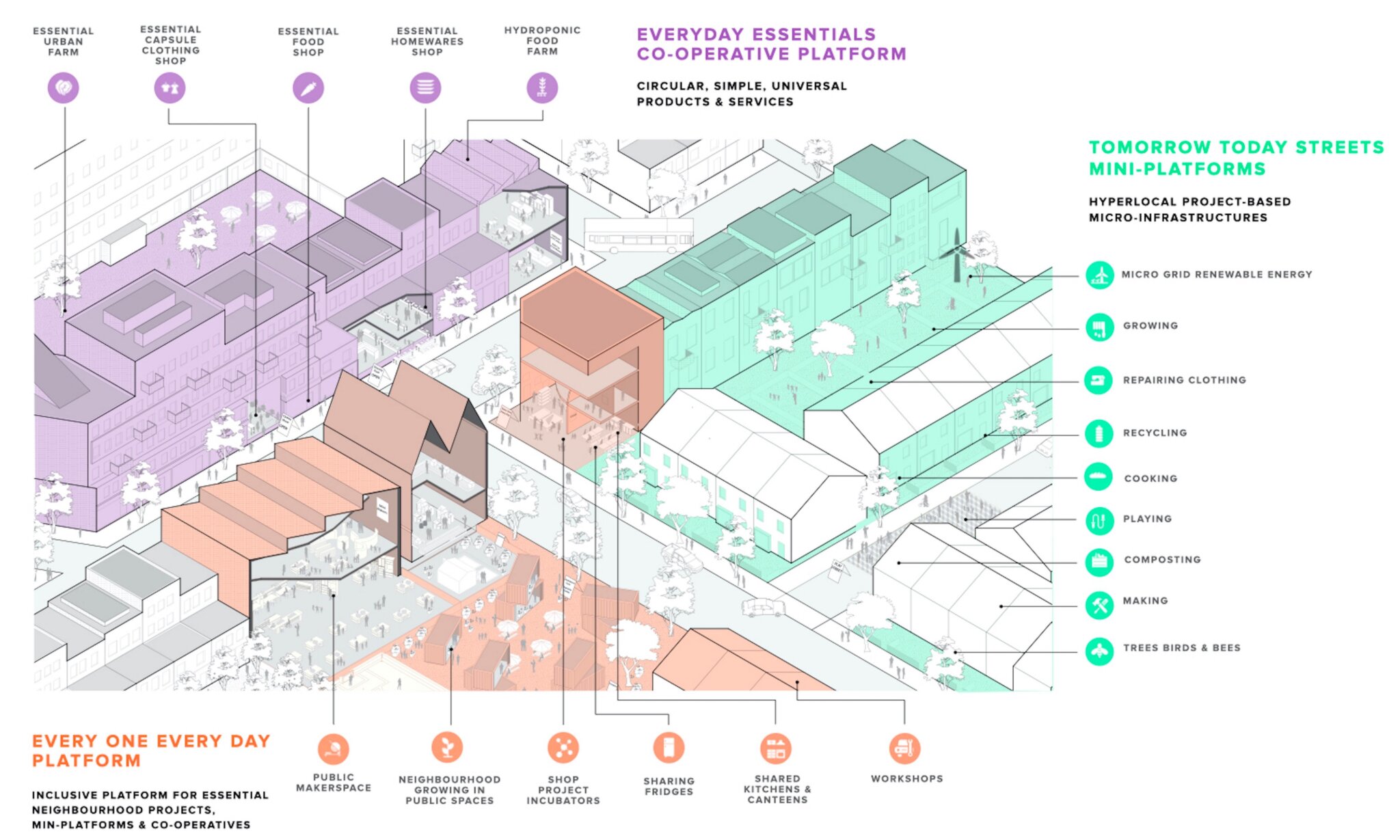

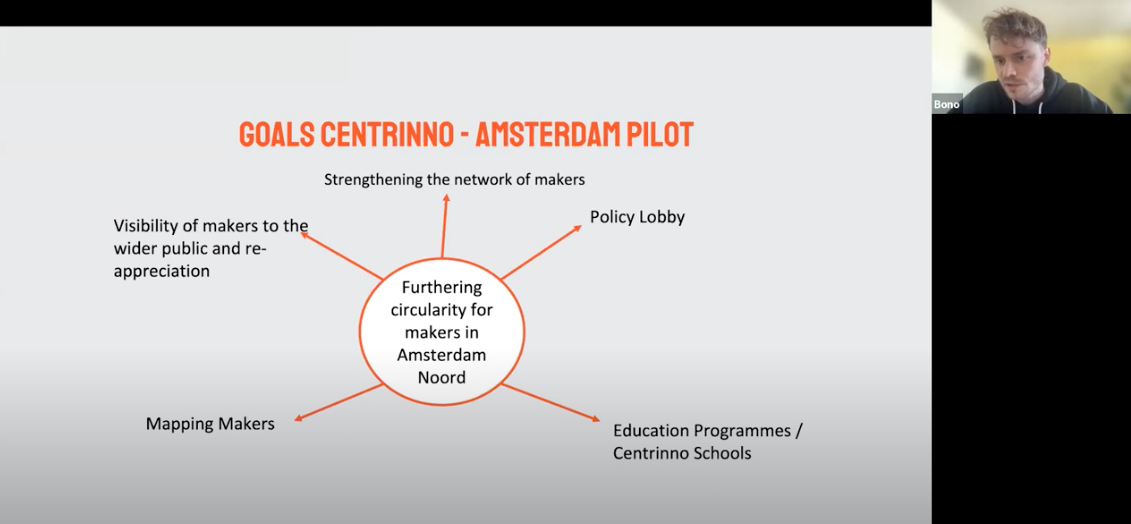

There are many different ways to exhibit information, artworks, archive material, narratives, relics, data, and so on. The exhibitions created by the CENTRINNO pilot teams explored some of these different methods, informed in principle by the Living Archive conceptual basis, as shown in Fig. 1 (and discussed in detail in the Living Archive Beta Version deliverable (up-to-date as of December 2023)). Important to remember when it comes to all the heritage work being done within CENTRINNO is the overarching goal of trying to prime spatial transitions of industrial areas to be more sustainable and circular.

So how has this been achieved in CENTRINNO? Certain traits, such as a future-facing perspective, is something common across all the exhibitions within the project. In Amsterdam, for example, with the pilot looking ahead to a circular 2050, the ‘Makers van Noord’ exhibition ‘allows visitors to ‘meet’ ten different makers from the area and learn their stories about reuse, sustainability and traditional craftsmanship. Visitors were encouraged to think about what their city might be like without… shoemakers, woodworkers and car mechanics?’ It also formed part of the Amsterdam pilot’s wider activities in which they aimed to highlight the community of makers in the Dutch capital

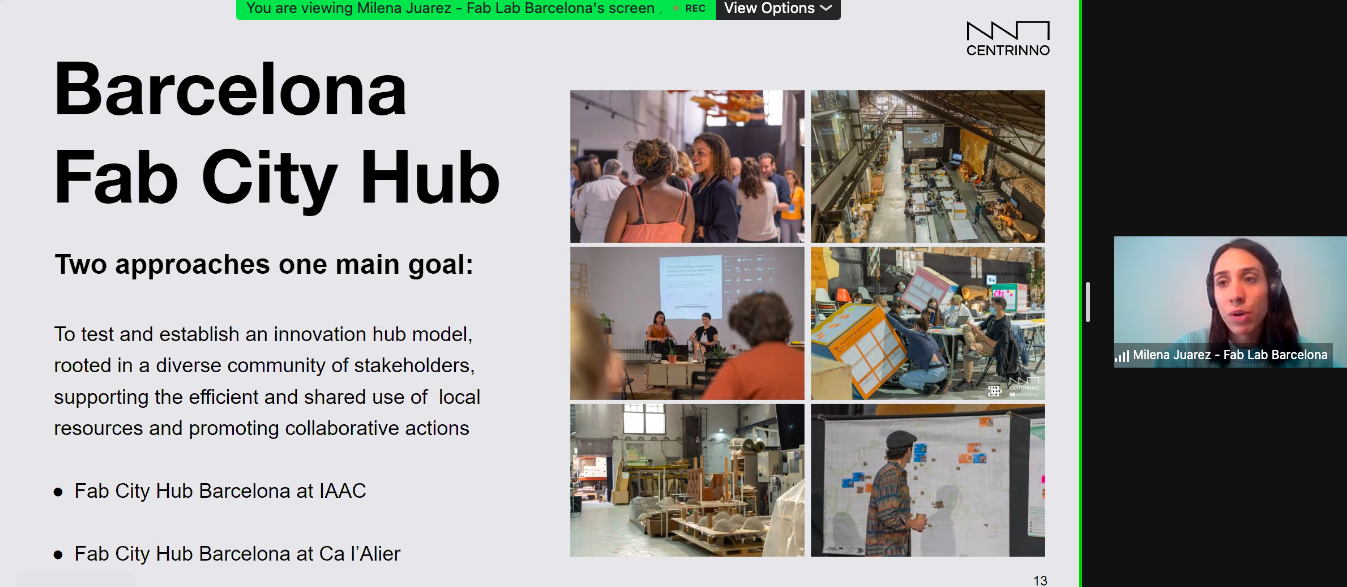

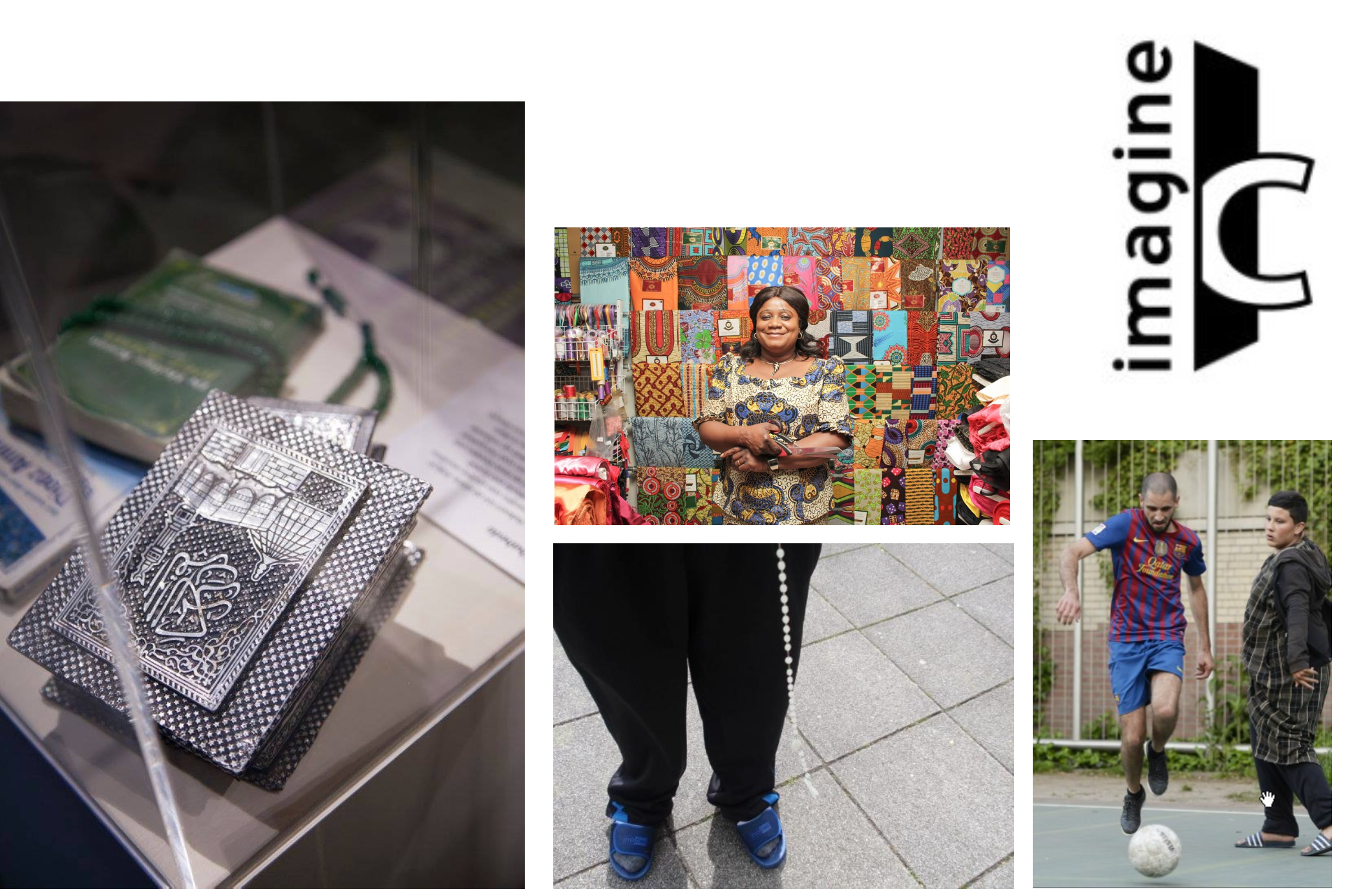

Of course, exhibitions are also always going to vary on account of their individual contexts, and on the contexts of the collections, and the data found therein. This is one of the beauties of local collecting, something enthusiastically espoused by Imagine IC, one of the partners of the CENTRINNO project, whose approach to exhibition making and collecting of materials informed the approach of heritage work throughout CENTRINNO. Two other pilots whose collections took a particular colouring because of their local context are the Barcelona pilot and the Copenhagen pilot. We took a deeper dive into what exactly they did, in order to consider how this could contribute to the project’s overall goal of circular living, as well as possibly contribute to the landscape of museums and exhibitions more broadly.

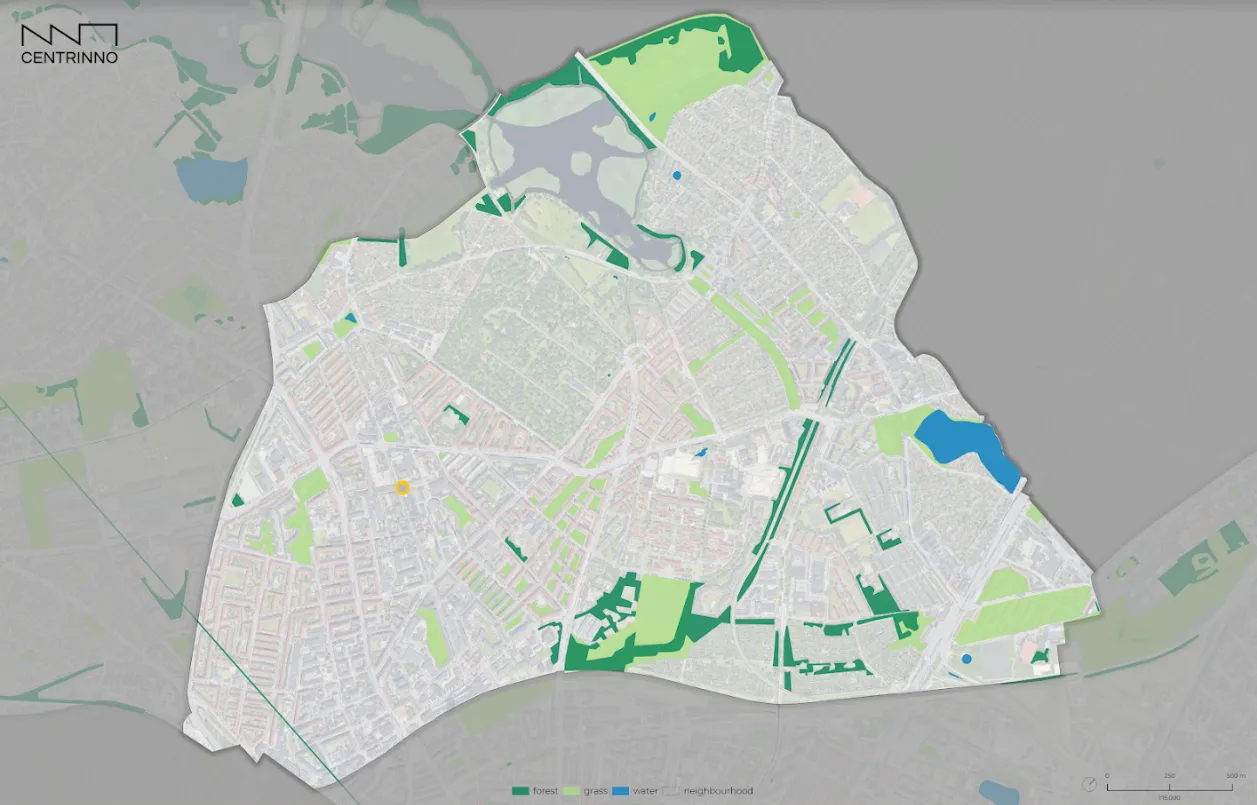

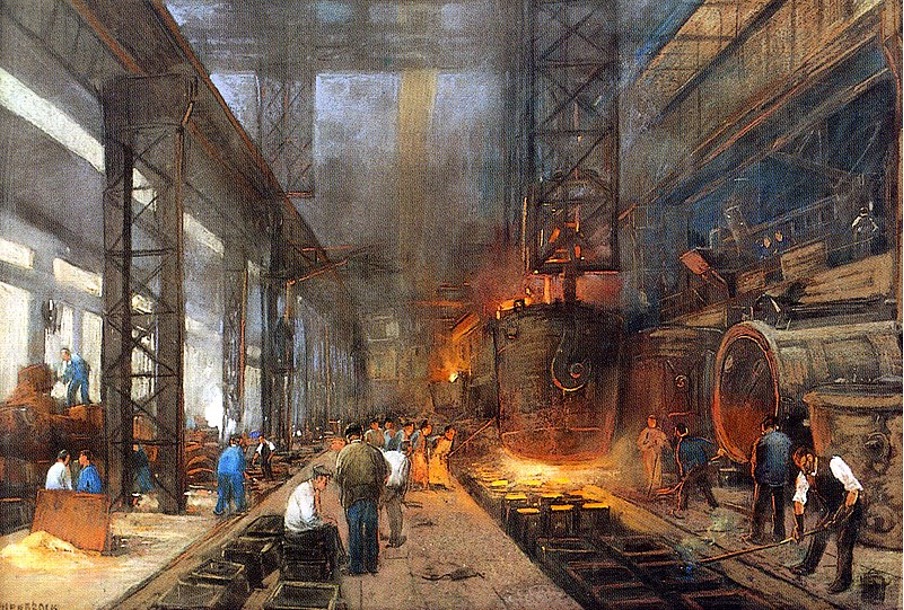

Copenhagen: A history explored through a collaborative spirit

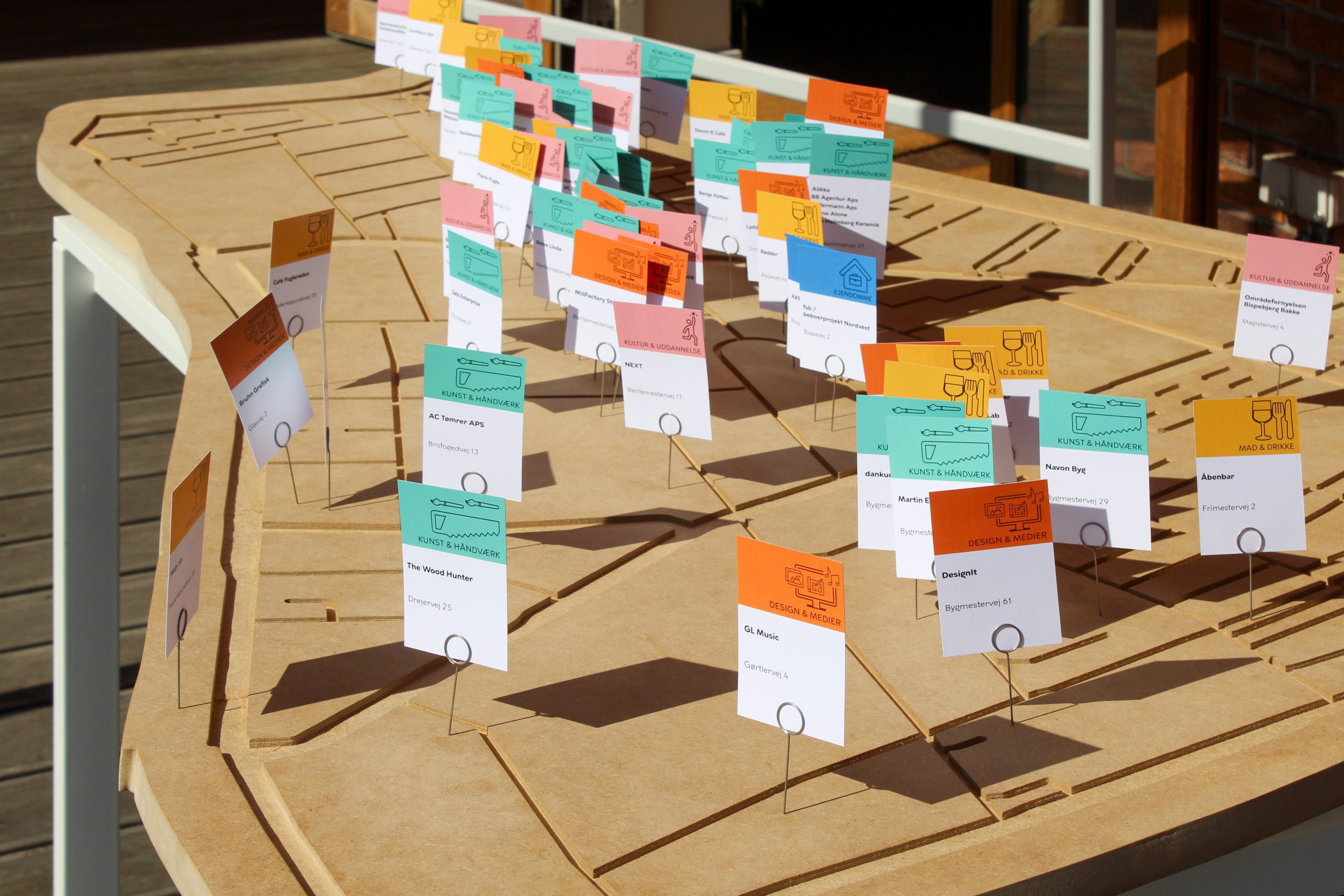

Over one month, the Copenhagen pilot experimented with an exhibition format that saw the elements of the Rentemestervej area collected and displayed across two different locations. The pilot’s ongoing relationship with a local library and community space saw them use the location as a base for the exhibition. The library, being situated within the local community as a place for gathering and gaining knowledge, made it a perfect place to embed the heritage of the area, as local history became enmeshed within a space of today’s daily life. Within the library, the pilot exhibited artefacts from and about the neighbourhood, focusing ‘on the industrial heritage of the area… zoom[ing] in on both the past and present, but also how the knowledge of the past can/should influence the development of the area in the future.’ [1] Within this examination was both an implicit and explicit posing of the dilemma of the area today: the balancing of the area’s steady gentrification into something similar to elsewhere in Copenhagen, against the need to maintain space for local production, in line with the area’s history. This was achieved via the arrangement of objects, maps, and texts relating to the area’s industrial past, as well as the inclusion of an interactive aspect that allowed visitors to contribute their own thoughts to the conversation. Accompanying these were stories from the CENTRINNO Living Archive, interspersed throughout the exhibition, with invitations to go and visit the podcast.

Fig. 2 – Displayed items in the Copenhagen exhibition

The exhibition aimed to create an experience that allowed for the agency of the visitor to be part of the space. This includes the movement between different areas within the exhibition. Speaking with the Copenhagen pilot, I learnt that the aim was to create a ‘multisensorial experience’ that activates different senses upon the movement between areas. This idea of motion complimenting the perception of an experienced past was not something developed in isolation: it was also present during the heritage bicycle tour that the Copenhagen pilot organised in the Rentemestervej area. A sense of fluidity and transition thus was generated, as an exploration of the move between past, present, and future, encapsulated by the ‘future form’, a form on which people visiting could write their hopes for the future of the area.

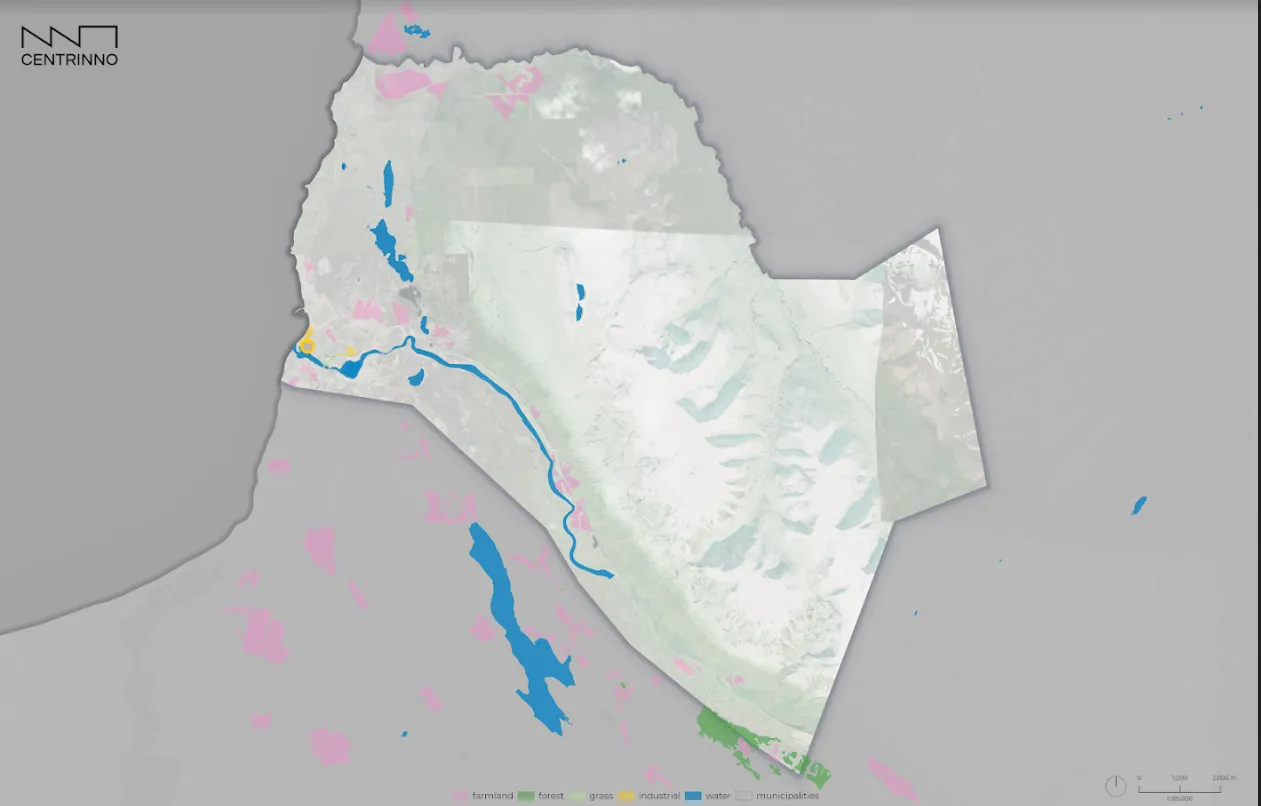

In accordance with these fluid movements from past to future, an accompanying public exhibit of photography was installed on the premises of NEXT, as part of the continued relationship with the local vocational school, NEXT. NEXT has been working with the Copenhagen pilot in the training of the young professionals of the future, via a range of crafts which have roots in heritage traditions involving wood, metal, and other materials. With their larger-scale images of selected students at the school, the public portraiture intended to ‘create a strong narrative about the district’s industrial heritage and the craftsmen of the future who have their daily routine at the school.’ Aiming to make NEXT as an organisation more visible in the neighbourhood (it is located in a fenced-in zone), the public photo exhibition places their relationship with craft at the centre of the framing, tapping into a rich tradition of making, and, again, placing the past and future in the same space. NEXT also wished to make the students proud of themselves and their profession and inspire young people in the neighbourhood to choose a vocational education.

Overall, the exhibition engaged with unpicking and reassembling the perception that people – both local inhabitants and visitors – had of the Rentemestervej area, or Nordvest more broadly. Could the relationship between community and local space be affected? What would it mean for the area going forward, if the perception of the area shifted?

Fig. 3 – The public portraits of makers from NEXT.

Perception is, after all, a vital part of the way in which a neighbourhood is experienced. In this particular area, the tensions between the oblique oppositional forces of deindustrialisation, criminality, redevelopment and gentrification each play a different role in how the area is understood. One of the Copenhagen pilot team explained that the Danish capital as a whole is broadly understood as a ‘fairytale’ city, an eco-utopia in which Hans Christian Andersen characters could presumably freely wander in whimsical ways. There is also, however, a steeliness and a grit beneath this conception of the city, one rooted in the industrial areas such as the Copenhagen pilot site. That these areas have often been perceived as ‘smelly or dirty’, speaks to a simplified narrative of industrial space that the exhibition seeks to unpick and revisit. At the same time, the fact that the neighbourhood was previously described as a place where ‘the alcoholics used to protect the children from the drug addicts’, as opposed to today, where ‘families walk around with fancy coffees’, finds these external perceptions in equally murky territory. [2] Is the former description more ‘true’ to the spirit of Rentemestervej, or the latter? The heritage items and stories gathered by this exhibition, which don’t directly address, for example, gentrification, but tangentially explore it through a wider description of the local histories, serve to probe and investigate these questions.

Barcelona: Framing futures on dual planes

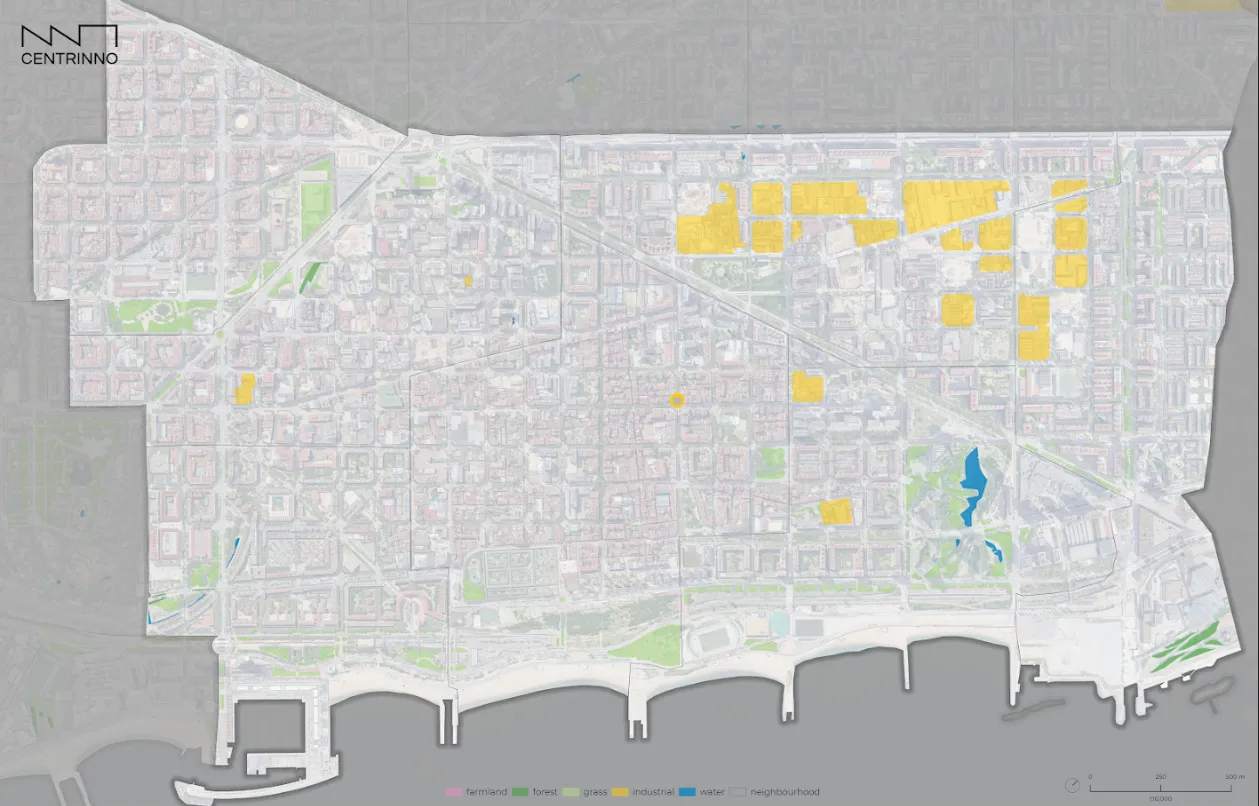

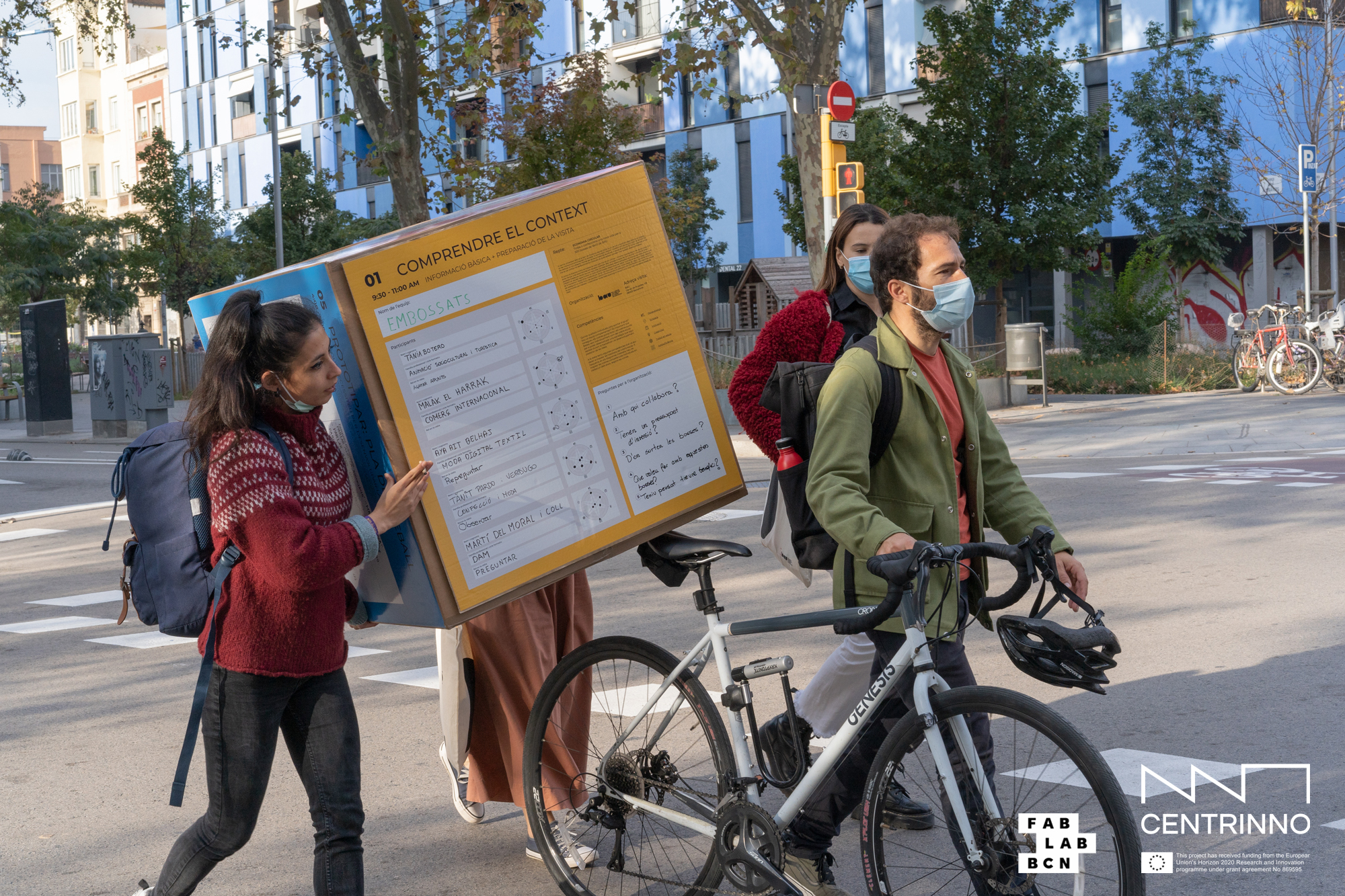

The Barcelona pilot, whose exhibition at Ca L’Alier ran from May 5th to June 15th, 2023, took a similar approach to that of Copenhagen, in the combination of materials relating to the past, present and future. Curiously, this happened without any communication with the Copenhagen pilot that this would be the chosen approach, indicating that the perspective on heritage running throughout CENTRINNO had some key resonances across pilots. [3] In the Poblenou exhibition (also described in detail in another blog post) however, the pilot’s approach was separated across two interconnected planes. On the one hand, the pilot gathered materials, artefacts, and stories grounded in the history of the area. On the other, the Barcelona partners organised a program of activities connecting to the overall themes of the exhibition, but with a prioritisation on the practicalities of crafts, which themselves are rooted in the local community of makers and craftspeople.

Fig. 4 – Section of the ‘Past, Present, Future’ layout of the Barcelona exhibition in Poblenou. Image credit Fab Lab Barcelona.

The exhibition’s physical installation involved a collection of tangible materials and stories representing the heritage of Poblenou – known colloquially as the ‘Catalan Manchester’ – and the path it took through time to reach the present. The exhibition’s primary focus was on the materiality of fabric, a nod to the district’s history of textile production, and was organised into three sections: ‘Past – Territory of Fabrics’, ‘Present – Territory of People’, and ‘Future – Cofabricating the Future.’ (An extensive gallery of images can be found here). Featured were the output of local makers working within the realms of sustainable production, many of whom were also the subject of stories submitted to the CENTRINNO Living Archive. Having a main material focus in this way allowed for the Barcelona pilot to present a connecting thread (pardon the pun!) between the industrial capacity for production between different eras, and so link the concerns of the city’s industrial heyday to the urgencies of the present, including the needs for more sustainable and circular living and manufacturing that underpins the entire CENTRINNO project. Likewise, these themes were differently interpretable depending on the direction of time the visitor followed. Someone visiting the future section first might envision possible futures before seeing their foundation in the present and the past, while someone visiting the past section first could see the building blocks of this foundation chronologically. Augmenting this process was an interactive call-to-action upon the moving between different periods, encouraging visitors to consider these alternative temporal scales as necessarily interconnected.

Fig. 5 – The connecting thread of Poblenou’s industrial history. Image credit Fab Lab Barcelona.

The supplementary layer of the Barcelona pilot’s exhibition work was a series of workshops, round table discussions, interviews with experts, museum directors, and historians, which provided an alternative method for considering the future of the Poblenou via a more interactive approach. Such events encouraged the incorporation of heritage elements, such as photographs of ‘neighbourhood heritage’, or the construction or manipulation of heritage elements themselves, as a way of showing the connection of heritage to people’s daily lives. The closing event, involving a workshop where participants shaped recycled clay, exemplifies this. Visitors were asked to consider, when it comes to a material like clay, why and what should we preserve, what do we keep, and what do we reuse or renovate? Such questions allowed participants to probe their own involvement with the crafts and materials characterising the Poblenou district.

In their probing of matters relating to the future (of the past) of Poblenou, the exhibition curators thereby sidestepped the didactic approach of telling visitors what a future of Poblenou should be like. Instead, it poses the issue of heritage as an open question, something to be collectively decided and worked through – whether difficult or harmonious – with the emphasised benefit of education and the capacity to access it. The associated ‘Hackathon’ event provides one example of this: how, the pilot asked, would students like to shape their own way out of the complexities of the present?

Fig. 6 – The host of the recycled clay shaping workshop held at the exhibition’s closing event. Image credit Fab Lab Barcelona.

The museum of the future

The exhibitions of the Barcelona and Copenhagen pilots therefore funnelled the circularity and inclusion ethos of the CENTRINNO at large into installations showcasing the particular and unique contexts of the local area. In doing so, they provide a template for other museums grappling with the difficult problem of how to understand the purpose of museums in the context of the issues facing modern societies today, including the looming threat of climate collapse, and the disparities of opportunity facing a young generation trying to make their way. The exhibitions could therefore be placed alongside complementary projects such as the Museums for Climate Action initiative, or prospective research into industrial memorialisation such as that proposed by CENTRINO-affiliated researcher Ashley Laflin. Such a reorientation of museum and exhibition practice may be a crucial tool for helping societies make sense of the urgent issues facing our present moment.

References

[1] Ashley Laflin et al, ‘Deliverable D4.4’, CENTRINNO, forthcoming, publication date TBA.

[2] Conversation with Copenhagen pilot team.

[3] Conversation with Barcelona pilot team.