BLOG

Seizing the hidden opportunity of recycling wood waste

Seizing the hidden opportunity of recycling wood waste

Seizing the hidden opportunity of recycling wood waste

Wood has been portrayed as a ‘versatile material’. It is renewable, reusable, and also biodegradable. Despite the potential, our wood value chain has yet to be circular. Annually, 50.2 million tons of wood waste were generated within 28 EU countries (Borz?cki et al., 2018). But only 70% of them were treated (Cocchi et al., 2018). The most typical way to treat this wood waste is by converting them for energy recovery and recycling. However, not all wood waste can be salvaged. A considerable high-quality waste wood is often not collected or separated, and thus being burned or disposed of in the landfill.

This under-utilized wood waste includes the wood waste generated from the tree maintenance and the construction and demolition waste (CDW). In the US, almost 36 million trees are taken down annually due to aging or new development, costing the country nearly $786 million. The latter part, CDW, contributes to more than a third of the waste generated in the EU (Next City, 2022). The recycling and material recovery of CDW across the EU varies from 10% to 90% as the challenges (e.g., standardization, waste handling services) differ per country.

So can our cities tackle urban wood waste and simultaneously reduce the number of trees we need to cut? Can we harness the potential of abundant wood waste by rethinking a way to close the loop in our wood value chain on a local scale? To do that, let us take a closer look at the potential of these two streams of wood waste: urban tree operations and building deconstruction.

GIVING SECOND LIFE TO FALLEN TREES

“Wood is reused as high-quality as possible and that not a single chip is wasted” – Stadshout

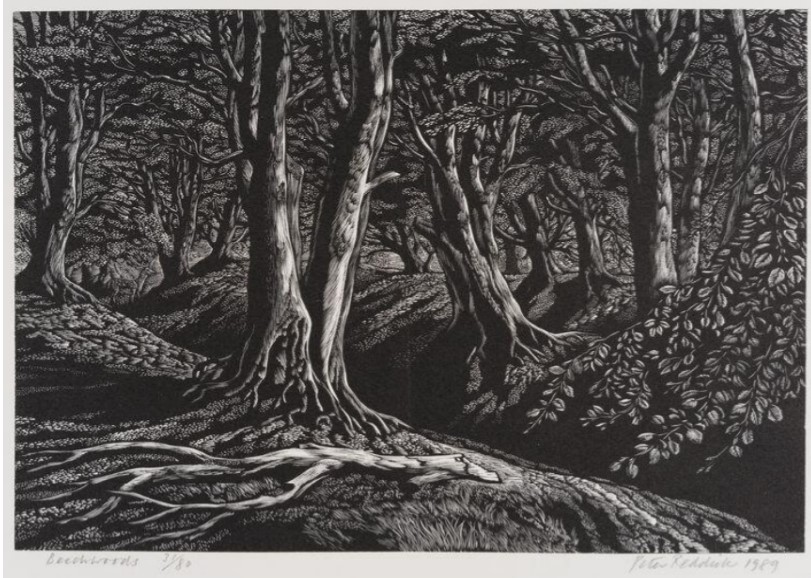

Urban greening has become a vital strategy in designing climate-resilient cities. A dense urban canopy can reap many benefits, ranging from cooling temperatures to improving well-being. However, maintaining trees is not an easy task. Due to storms, disease, or expansion of land development, many trees are falling or being cut down. In response, Stadshout, a sawmill based in Amsterdam, gathers tree trunks around the neighborhoods and transforms them into usable wood. Working together with craftspeople, they produce unique products and get involved in public projects to promote the use of this local urban wood. They also provide a platform (flagship store) for local artists to display their sustainable wooden products.

A similar approach is taken by Bay Area Redwood. Established in 2018 in California, Bay Area Redwood has a mission to reclaim urban felled trees, putting them into higher use, such as milling slabs or artisanal wood products with local craftsmen. Apart from working closely with arborists, this company also applied circular business models by connecting the users with several mills, providing services from tree removal to processing with partnered arborists and mills. Both companies are committed to building circularity in the wood value chain by ensuring that the wood derived from the fallen trees can be preserved by giving them a new purpose.

Image 1. Bay Area Redwood workshop (Source: Bay Area Redwood)

Apart from the benefits of recycling wood, working at the neighborhood level allows businesses to engage more with the local communities and, at the same time, raise public awareness about circularity. Similar initiatives can also come from the community, as shown by Re:works in London. Initiated by 20 residents of Barking and Dagenham borough, Re:works salvaged materials from Victoria & Albert Museum and provide space for residents to collaborate in the workshop called ‘Every One Every Day’ programme where they are trained to create products from wood waste. The products are showcased in a retail shop and exhibited to inspire large organizations to also innovate with their waste.

RETHINKING THE LEFTOVERS FROM THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

“It opens up wood and woodworking to a whole range of people who might otherwise not have considered that.” – Forust (From Forbes)

The construction industry has contributed 5-12% of the total GHG emission in Europe. Looking closely, the amount of wood waste generated from the construction industry accounts for 35% of the total waste nationwide. By 2020, the EU has targeted this waste stream to be recycled, reused, and recovered by 70% and promote high-quality recycling and reuse. In Northern Europe, the wood waste from CDW is mainly used for energy production, e.g., biomass. The rest, in high quality, such as solid wood, are utilized as panelboards by local panel manufacturing. But still, a large portion of wood waste, particularly of lower quality, is not reused effectively and ends up being incinerated or landfilled.

One of the ‘leftovers’ are sawdusts, often deemed detrimental to the environment as they contribute to air pollution. Forust, a company based in Burlington, brings an innovative approach in the light of this issue by recycling the remaining sawdust and lignin using 3D printing technology. They turn them into composite wood particles with bio-epoxy resin. Thanks to this cutting-edge approach, the outcomes range extensively, from small decorative works to large interior design products. To make it better, no woodworking experience is required. It allows customers such as architects and designers to customize the output design, from the type of grain to the complexity of the shape, which is hard to acquire using traditional methods. With 3D printing technology, it is possible to produce on a large scale and fulfill high-volume demands on wood-based products. If previous examples show the potential of recycling wood at a community level, Forust, on the other hand, offers the possibility of valorizing wood waste at a meaningful scale.

Image 2. 3D printed wood products from Forust (source: Forust)

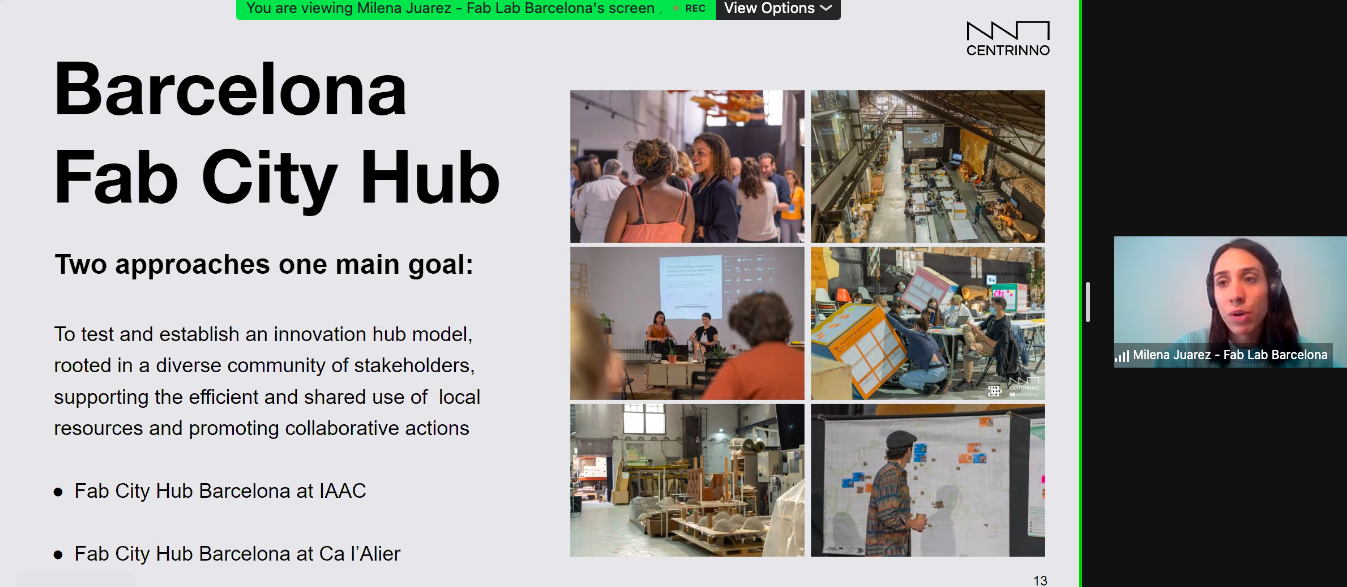

WOOD WASTE IN CENTRINNO’S PILOTS

“What is the potential of making urban wood waste in Barcelona circular?”

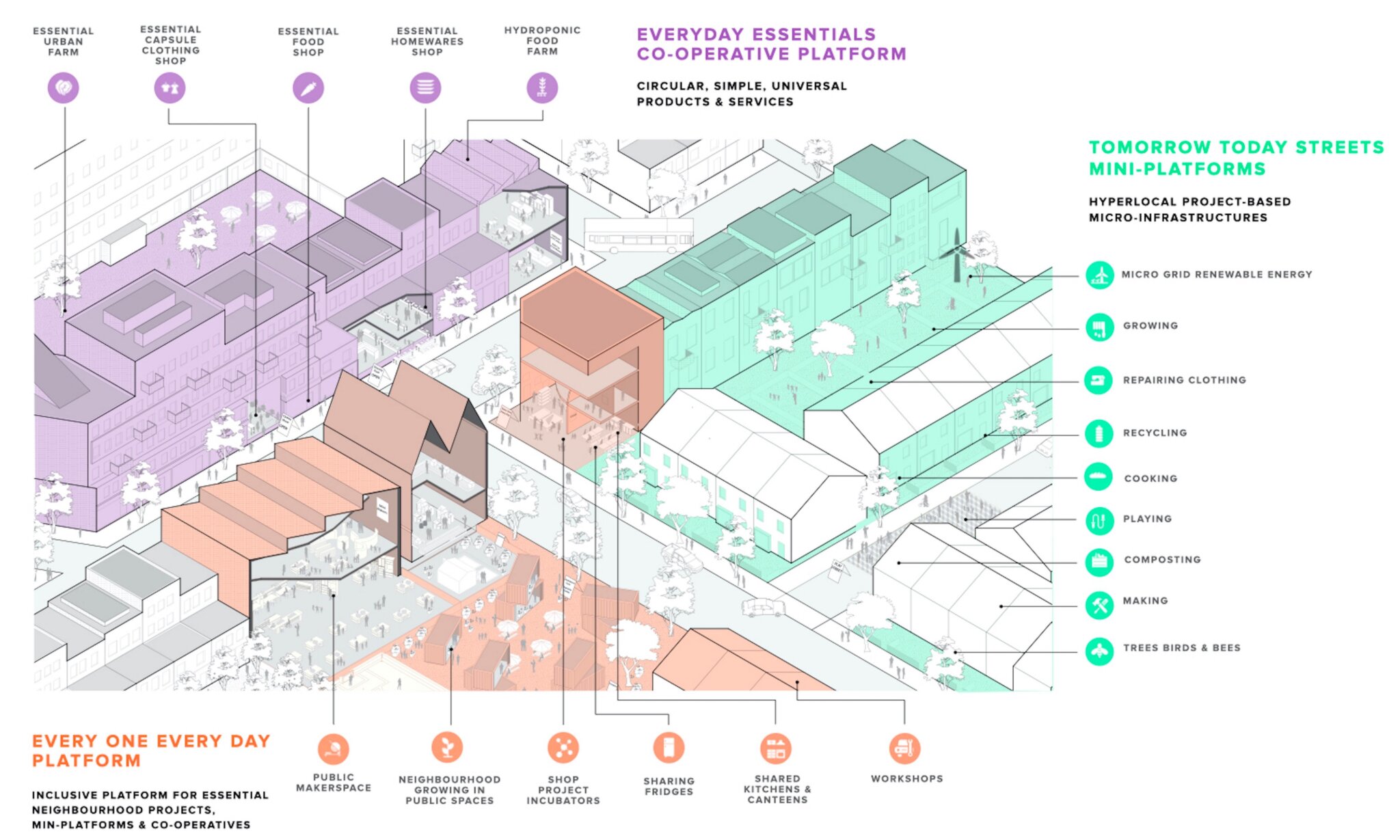

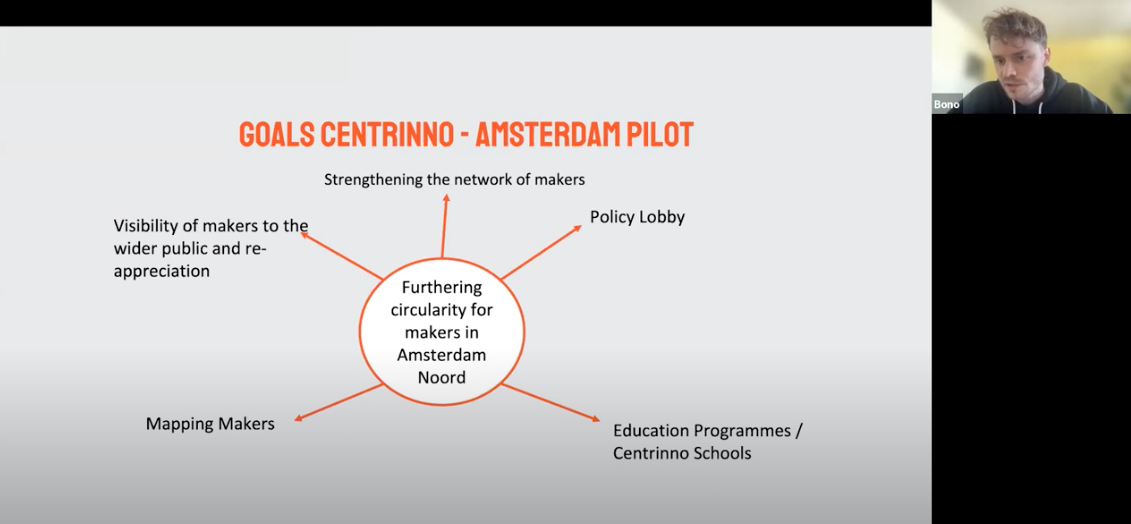

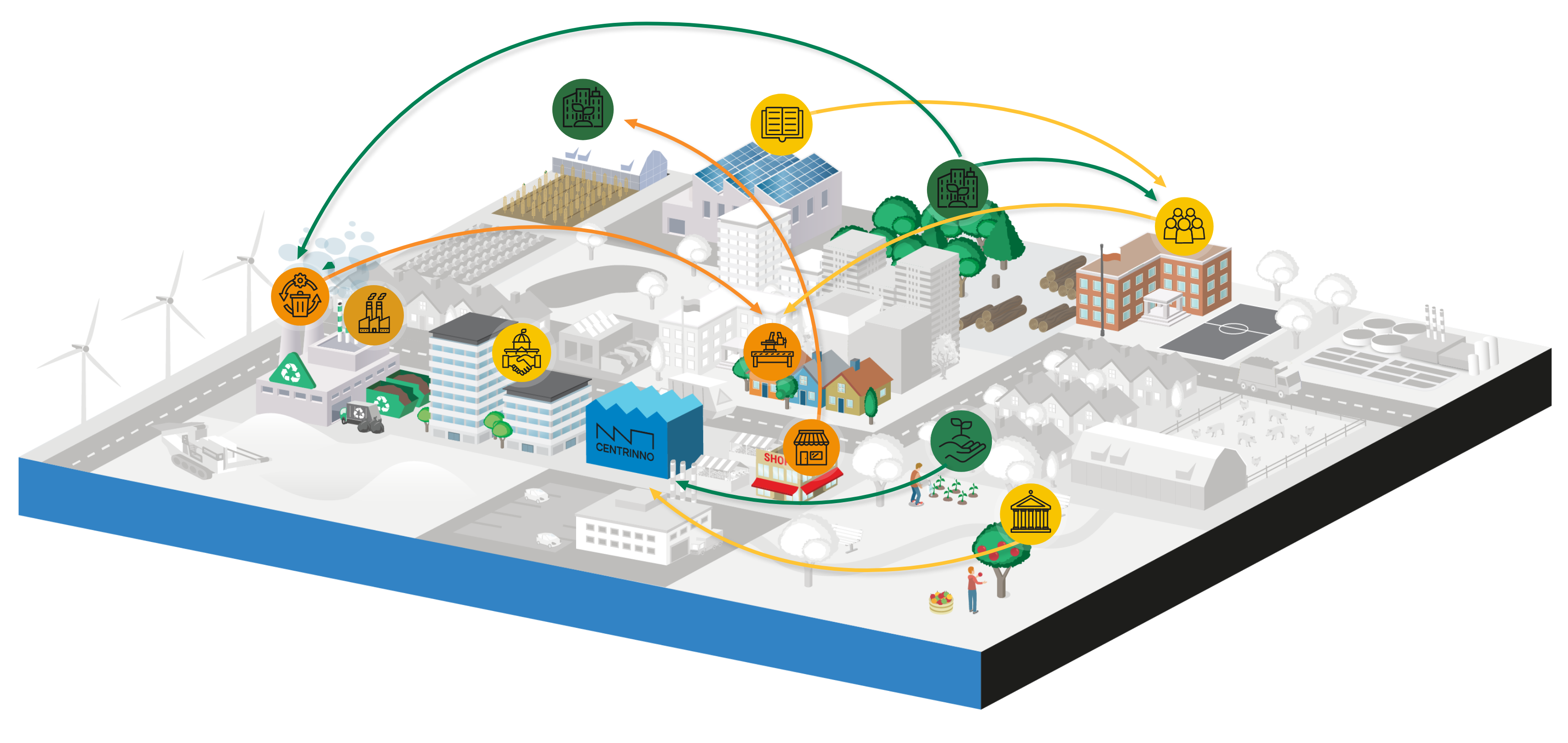

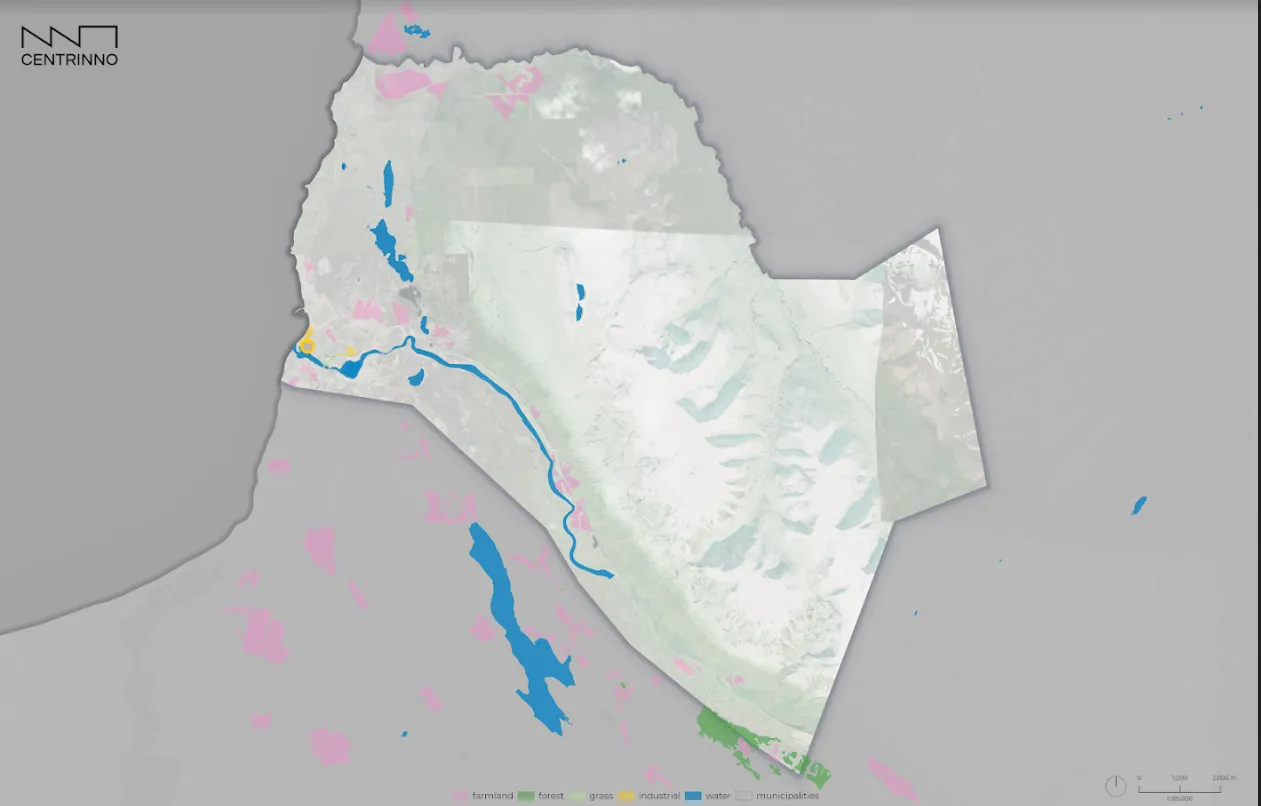

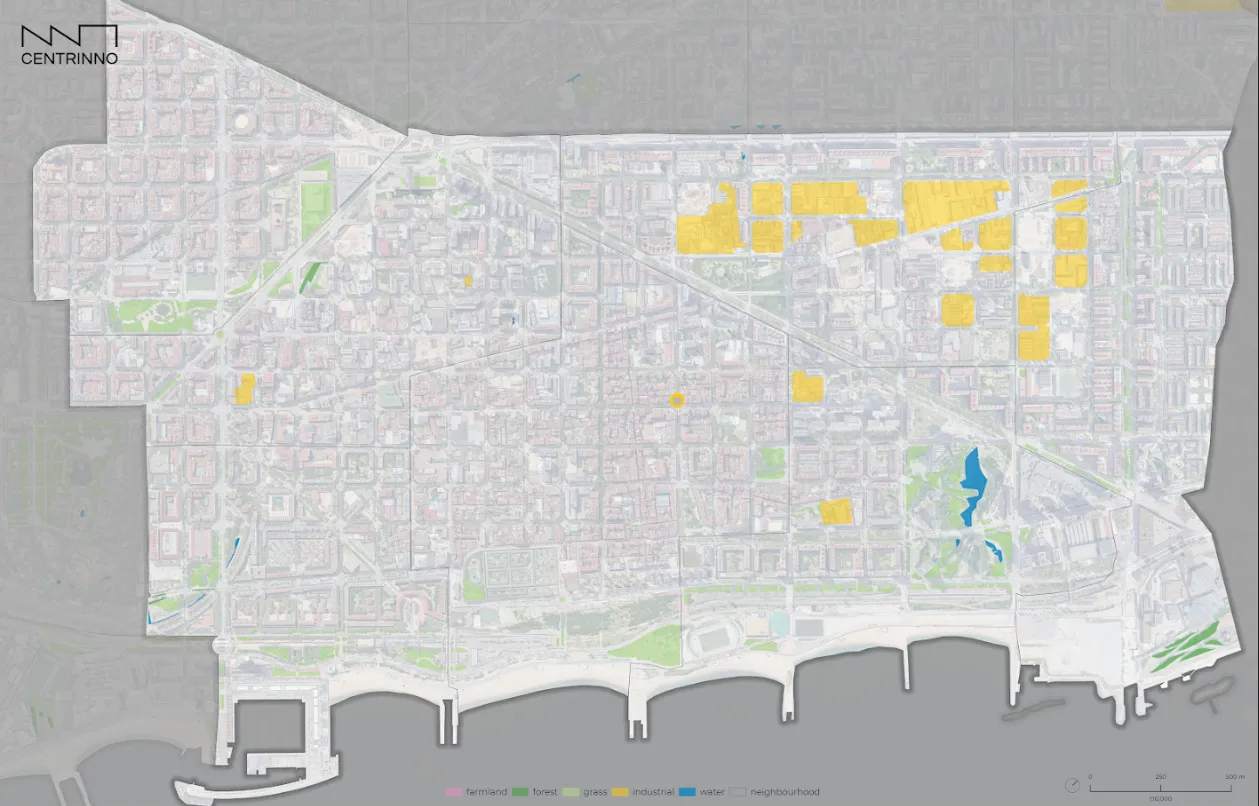

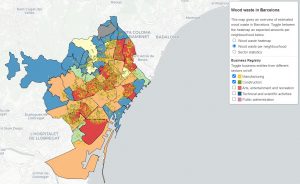

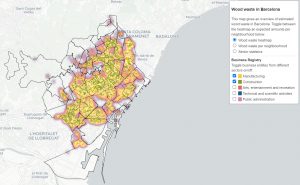

The initiatives above show that the potential of circular wood business models is manifold, from neighborhood to industrial level, from local to global scale. In one of Centrinno’s pilot cities, Barcelona, the number of wood waste in urban areas is estimated from 100-500 tons per year per neighborhood; most is generated from the construction and manufacturing sectors. The old industrial area, Poblenou, as the center of CENTRINNO Barcelona pilot, is one of the most significant contributors to wood waste. The map below shows the potential volumes of annual wood waste based on public business registry data and Eurostat waste statistics. .

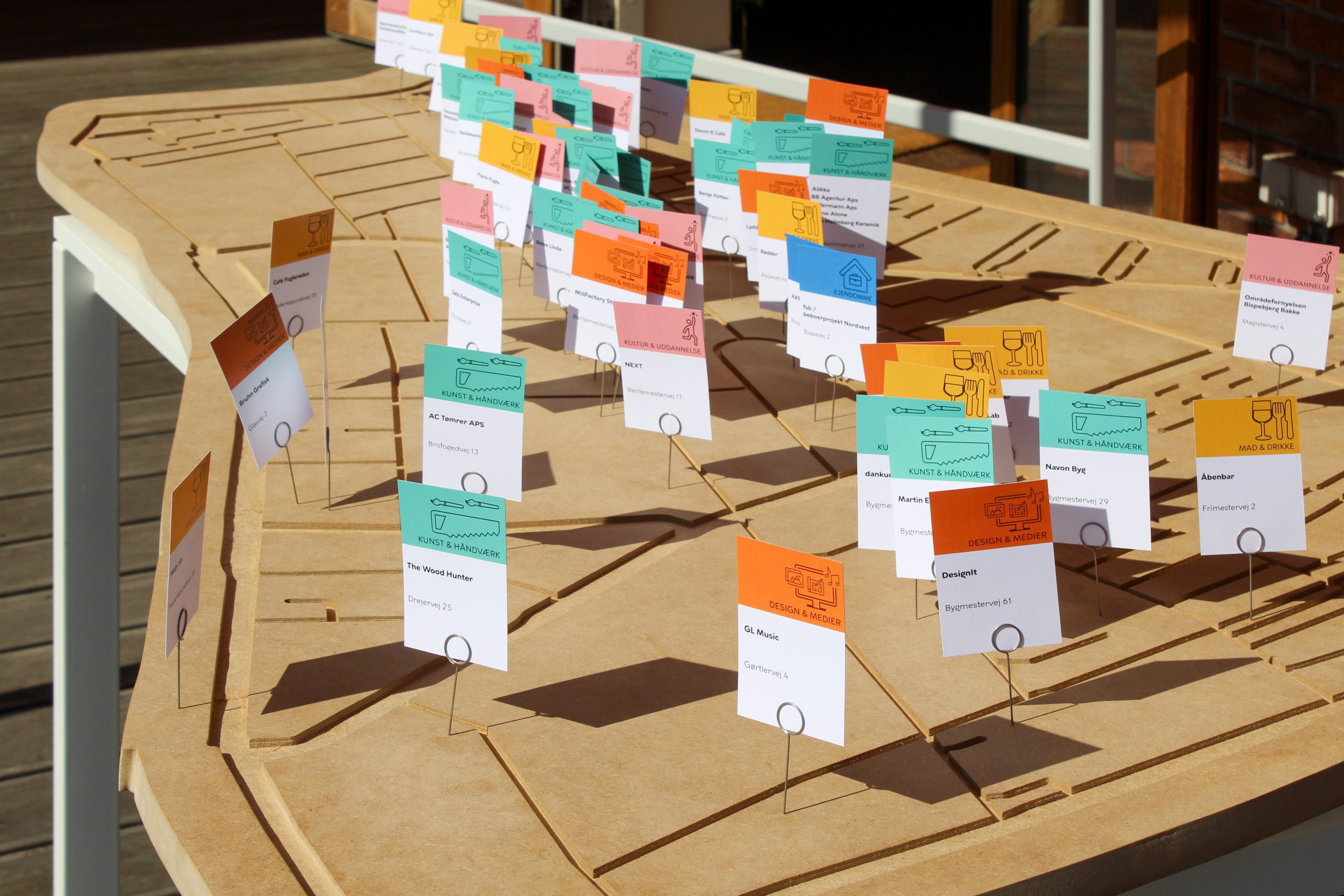

The CENTRINNO Pilot in Barcelona has been carrying out a combination of bottom-up and top-down mapping analysis to understand the potential of wood circular production for Poblenou and Sant Marti district. The main focus of the urban ecosystem mapping in the pilot has been to explore the interactions and possibilities held by wood as a resource for the developing of new products and services, while mapping the social connections and knowledge exchange related to it.

Bottom-up

The bottom-up mapping for the Barcelona pilot aims to identify the hidden resources and roles played by small producers, makers and local businesses in Poblenou and Sant Mari districts. An ongoing analysis has been undertaken to promote collaborative actions among local stakeholders and to visualise manufacturers’ role in improving materials’ circularity.

The goal of these interviews is twofold: First, it has been used to engage and list new manufacturers, fabricators and workshop facilities to the Make Works platform. Second, it has been used to identify drivers, obstacles and potential synergies for fostering a circular and productive neighbourhood culture. The survey includes the identification of data related to types of materials, amount of waste being generated, machines, processes, traditions and other capacities and skills by the local manufacturers.

Top-down

In parallel with the bottom-up data collection, the CENTRINNO Barcelona pilot has been developing an urban wood stock analysis (high level capacity context map) in collaboration with Metabolic Institute. This analysis will serve as a showcase for understanding the capacity of recovering materials and producing circular products made from wood in Poblenou. The research has been done through urban mining analysis to understand the availability of wood from different typologies of buildings and, through urban vegetation mapping, to estimate the potential wood to be recovered from urban trees.

By exploring the potential local circular economy, the local pilot wants to support and contribute toward an inclusive and innovative urban ecosystem, inspiring the creation of circular business models around wood in other Barcelona’s districts and beyond.

Image 3. Wood waste in Barcelona per neighborhood (Top), Wood waste heat map based on manufacturing and construction businesses (Bottom) Interactive map

- Conclusion

WAY FORWARD FOR OUR CITIES

Reflecting on the abundance of potential is indeed inspiring. Still, it is also essential to look at the bigger picture of how such initiatives contribute to the more extensive system and how they can drive the industry to shift to circularity. For example, one of the REFLOW cities, the region of Île-de-France in Paris, consumes 220,000 tons of wood annually for construction. At a city level, 920,000 tons of wood waste is produced annually, yet only half is being recovered. The rest, 171,000 tons, 18,5%, ends up in landfills and incinerators. This number shows tremendous potential for recovering wood waste at the end of the pipeline. Learning from the case studies, four actions can be taken by cities to spur the development of circular “wood stock” in the future:

1- Identify hotspots in the value chain & save the good quality of wood waste

Cities can start by analyzing what lies at the end of the wood value chain. The most significant potential often remained hidden and untouched in the value chain. When it comes to wood waste, as shown in the examples above, these local businesses start looking at ‘dead cycle’ material such as sawdusts as valuable resources. Moreover, cities can prevent good-quality wood from being disposed of to landfills by dedicating sorting and collection points in the city. As shown by Baltimore Wood Project, such a collection facility helps the local makers reclaim the wood and repurpose it for other uses.

3- Fill the gap in makers’ capacity

There is a list of good reasons why it is difficult to turn a lower quality of wood waste into useful material or product, such as lack of knowledge, suitable tools, or woodworking skills. In this case, Forust aims to tackle this challenge by offering flexibility in design. They use digital fabrication, and in this way, low-quality wood waste can be recycled easily. But in doing so, advanced technology and skills in digital fabrication are needed. Another set of tools that cities can similarly provide and facilitate, for instance, through collaborating with Fab Lab in engaging local businesses and communities in learning about digital fabrication through workshops.

4- Build a circular network

Often, the circular supply chain has not yet been well established. The makers then need to build a circular business model that can fit well into the current wood supply chain. This is a strategic move and sometimes requires more effort and costs. In the case of Bay Area Redwood, they partnered with people with critical jobs in the wood system, arborists and sawmills. And by doing so, they managed to create a meaningful connection with the local communities, as they functioned as the hub. Whenever people find problems with the trees around their neighborhood, they connect them to the ‘right’ people. Cities then can learn from this case by building a circular network, facilitating the connection between circular makers and suppliers and all critical actors in building a circular economy. As an entry point, the old industrial area can be utilized to connect these circular makers, to build inclusive hubs of entrepreneurship and foster innovation.

From the city level, supporting local wood value chains is like a ‘win-win’ solution; promoting local businesses, and simultaneously replacing wood products potentially contributing to deforestation and linked greenhouse gas emissions. But this initiative can only be leveraged if they are backed by cities. However, not all cities have set their eyes on this sector. And this can be a challenge for local businesses to flourish as they are challenging the ‘giant’ in the wood-products manufacturing industry. Without collaboration and strategic actions, it is so easy to sweep this opportunity under the carpet and keep it hidden. Or we can start looking at this hidden gem, utilizing our industrial historical sites, and now seize the chance to build a circular wood value chain.

- References

1 – Borz?cki, K., Pude?ko, R., Kozak, M., Borz?cka, M., & Faber, A. (2018). Spatial distribution of wood waste in Europe. Sylwan, 162(7), 563-571.

2 – Cocchi, M., Vargas, M., & Tokacova, K. (2018). BioReg: D1.2: STATE OF THE ART TECHNICAL REPORT. BioReg. https://www.bioreg.eu/assets/delivrables/BIOREG%20D1.2%20State%20of%20the%20art%20technical%20report.pdf

3 – Next City. (2022). “Reforestation Hubs” Are Saving Urban Trees From Heading to Landfills. Geraadpleegd op 14 juli 2022, van https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/reforestation-hubs-are-saving-urban-trees-from-heading-to-landfills